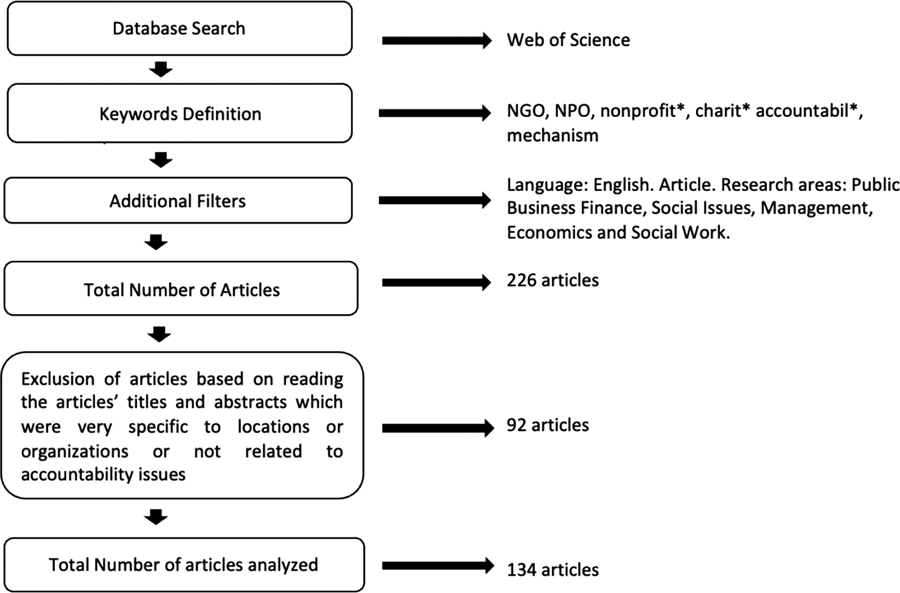

FIGURE 1. ARTICLE SELECTION AND KEYWORD DEFINITION

NGO ACCOUNTABILITY TO DONORS: BETTER SAID THAN DONE

RENDICIÓN DE CUENTAS DE LAS ONGS ANTE LOS DONANTES: ¿MEJOR DICHO QUE HECHO?

María Jesús Ríos Romero (Universidad Complutense de Madrid)1

Elena Urquía-Grande (Universidad Complutense de Madrid)2

Carmen Abril (Universidad Complutense de Madrid)3*

Fecha de envío: 15/09/2022. Fecha de aceptación: 29/11/2022

Abstract

The growing involvement of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in solving development problems has led to an increase in the number of NGOs around the world and therefore in their visibility and influence. Although concerns about the role and responsibility of NGOs have been raised from more than 20 years, there is still a need to ensure good practices in NGOs and to determine what measures will improve NGOs’ accountability to their stakeholders. Our study aims to contribute to this initiative from the donor accountability approach. To achieve this goal, we conducted a systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis to analyze the constraints and needs that donor accountability pose to NGOs. Our findings suggest that donor accountability could interfere with NGOs’ activities, leading them to generate short-term results, focus more on financial results, and feel increased pressure on overhead costs. The most recent literature opens an opportunity, however, to make upward accountability more useful for NGOs. Following this trend, we propose that donor accountability be considered as a dimension to assess NGO quality so that it becomes a powerful marketing tool to attract and retain donors.

Keywords: NGO, nonprofit.

Resumen

La creciente participación de las organizaciones no gubernamentales (ONG) en la solución de los problemas de desarrollo ha dado lugar a un aumento del número de ONG en todo el mundo y a una mayor visibilidad e influencia. Aunque durante más de 20 años se han planteado el papel y la responsabilidad de las ONG, sigue siendo necesario garantizar las buenas prácticas en las ONG y determinar qué medidas mejorarán su rendición de cuentas ante sus partes interesadas. Nuestro estudio tiene como objetivo contribuir a esta iniciativa desde el enfoque de la rendición de cuentas a los donantes. Para lograr este objetivo, se llevó a cabo una revisión sistemática de la literatura y un análisis bibliométrico para analizar las limitaciones y necesidades que la rendición de cuentas a los donantes plantea a las ONG. Nuestros hallazgos sugieren que la rendición de cuentas de los donantes interfiere con las actividades de las ONG, lo que las lleva a generar resultados a corto plazo, centrarse más en los resultados financieros y sentir una mayor presión sobre los costos generales. Sin embargo, la literatura más reciente abre una oportunidad para hacer que la rendición de cuentas ascendente sea más útil para las ONG. Siguiendo esta tendencia, proponemos que la rendición de cuentas de los donantes se considere como una dimensión para evaluar la calidad de las ONG, de modo que se convierta en una poderosa herramienta de marketing para atraer y retener a los donantes.

Palabras clave: ONG, sin ánimo de lucro.

1. INTRODUCTION

Nonprofit accountability research has been extended over the last 25 years. While there is basic agreement on the key characteristics of accountability to whom, for what the NGO is responsible for, and how the information will be provided in the literature, there is not a clear differentiation on the specific issues of NGO accountability. One reason for this scarcity is that researchers tend to equal NGO´s with NPO´s and the term Nonprofit organization usually groups under the same category any nonprofits, charities, and NGOs. As an example, Cordery et al. (2019, pp.2) includes in their study “Our definition of NGOs incorporates terms such as private social purpose organizations, charities, not-for-profit organizations, non-profit organizations civil society organizations, social enterprises and service clubs”.

NPOs and NGOs have both similarities and differences. An NPO is based on the financial premise that no net profits from donations will benefit any individual. From this perspective, the concepts of NGO and NPO overlap: all NGOs are NPOs but not all NPOs are NGOs. Vakil (1997) proposed a tentative structural-operational definition of NGO as a self-governing, private, not-for-profit organization geared toward improving the quality of life of disadvantaged people. This definition is based on a study by Salamon and Anheir (1992), who also proposed an NPO taxonomy. According to these authors, NGOs are a subgroup of NPOs whose most significant differentiating elements are the causes that they address. These causes, and thus potential NGO categories, are equality, human rights, and empowerment.

These differences define characteristics of NGOs that distinct them from NPOs from the donors’ viewpoint, who demand higher moral capital and social legitimacy from NGOs that address more sensitive societal issues (Kane, 2001). Such donors or potential donors expect greater integrity and transparency from NGO than from NPO activities, and this difference should be reflected in NGOs accountability. An additional factor differentiating NGOs is that they depend largely on donors’ donations, while NPOs are financed primarily with company funds or family assets (i.e.: the Gates Foundation, INGKA Foundation, or J. Paul Getty Trust) which reduces, or almost eliminates, the need to attract donors (Bendell, 2006).

Fundraising is the main uncertain block for the survival and development of NGOs (Ha et al., 2022) and implies greater competition to attract donations. Hence, NGOs need to differentiate from their “competitors” and that differentiation can be achieved through accreditation, transparency, and demonstration of a clear accountability to ensure the NGO’s credibility (O'Dwyer & Unerman, 2010; Ospina et al., 2002; Schmitz et al., 2012). NGOs accountability also serves to build trust by demonstrating transparency in the use of financial resources and responsible and ethical behavior that meets stakeholders’ expectations (Agyemang et al., 2019; Bryce, 2006; Prakash & Gugerty, 2010; Sloan, 2009).Thus, accountability and reporting instruments could therefore be used to measure the quality of NGO and its reputation (Burger & Owens, 2010; Tremblay-Boire et al., 2016) enabling donors to evaluate the performance and compare the quality of different NGOs.

However, NGO accountability is a complex process. NGOs are expected to be accountable to multiple actors for multiple purposes (Ebrahim, 2010; Ospina et al., 2002; Unerman & O’Dwyer, 2006). Not only must they be accountable to donors, funders, volunteers, program beneficiaries, and society, but they have multiple purposes of finance, governance, performance, and mission. The size of the NGO and the cause it advocates can also influence the purpose of accountability and the stakeholders to whom it is addressed (Unerman & O’Dwyer, 2006). In addition, accountability process implies that NGOs have people trained in reporting and accountability requirements which generally is time consuming and expensive to produce (Agyemang et al. 2009; Burger & Owens 2010; Ebrahim 2003b; O’Dwyer & Unerman 2007; Schmitz et al. 2012, van Zyl and Claeyé, 2010).

This article aims to advance the knowledge regarding NGO accountability. Despite the growing importance of the number of NGOs in the nonprofit sector, and the fact that there are differences among NGOs and NPOs, little attention is still paid to those differences that we consider relevant to the accountability process. Accordingly, our study makes two contributions to the NGO literature. First, it gathers the accountability knowledge according to the three main areas: to whom, for what and how, and discuss the aspects that are most relevant to accountability in NGOs. Second, we identify the existing research gaps, given the NGO particularities, while proposing new avenues for future research on NGO accountability from donors’ perspective.

Our proposal is that NGOs accountability to donors is critical because, not only does it serve to comply with legal and economic requirements, but it also contributes to the accreditation of the NGO quality, which is relevant to organizations differentiation and attract donors.

This manuscript is structured as follows. First, we review the theoretical background on nonprofit accountability on “to whom,”, “for what” and “how” questions. Second, we describe the literature review process and the bibliometric analyses. We then conduct the analysis and discuss their results. In the final section, we present our conclusions, possible limitations and suggestions for further research.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Ebrahim (2003a, p. 815) considers that accountability “may be defined not only as a means through which individuals and organizations are held responsible for their actions (e.g., through legal obligations and explicit reporting and disclosure requirements), but also as a means by which organizations and individuals take internal responsibility for shaping their organizational mission and values, for opening themselves to public or external scrutiny, and for assessing performance in relation to goals”. Prior to that definition, Edwards and Hulme (1996, p. 967) defines accountability as “the means by which individuals and organizations report to a recognized authority (or authorities) and are held responsible for their actions” (Edwards & Hulme, 1996, p. 967). Similar definitions of accountability can be found in the literature where it is also established that a responsibility is assumed, and must be accounted for it (Costa et al., 2011; Cut & Murray, 2000; Murtaza, 2012; O’Dwyer & Boomsma, 2015).

Thus, accountability involves three fundamental parts: To whom the NGO accountable, for what the NGO is responsible for, which should include NGOs mission and values (Ebrahim, 2003a) and finally how that information will be provided.

2.1 Accountability “to whom”

When most academics raise the question of accountability “to whom,” they note its complexity due to the different stakeholders with which NGOs must deal. Accountability relationships are problematic because NGOs are expected to be accountable to multiple actors: upwards to funders or donors, downwards to beneficiaries, internally to themselves and their missions, and horizontally to other NGOs (Christensen & Ebrahim, 2006; Edwards & Hulme, 1996; Ebrahim, 2003a; 2005; Kearns, 1996; Lindenberg & Bryant, 2001; Najam, 1996).

Upward accountability to donors primarily evaluates the use of funds. Downward accountability to beneficiaries responds to the groups that receive the NGO’s services and assesses how they are being delivered (Ebrahim, 2005, 2003a, b; Edwards & Hulme, 1996; Lloyd, 2005; Najam, 1996; Urquía-Grande et al., 2017; 2022). There is also internal accountability to the NGO staff, who answer for the organization’s responsibility and its mission. Finally, NGOs’ horizontal accountability to other NGOs enables comparison among them (Ebrahim, 2003a; Ebrahim, 2010; Edwards & Hulme, 1996; Sowa et al., 2004). Thus, NGO accountability needs may vary depending on the stakeholder being considered (Brown & Dillard, 2015; Kingston et al., 2019).

NGOs tend to prioritize their upward accountability to demonstrate results to donors to justify their donations. However, this pressure on short-term results makes it difficult to implement long-term projects that might be more relevant to their optimal performance (Christensen & Ebrahim, 2006; Ebrahim, 2003a, 2009; Edwards & Hulme, 1996; Kilby, 2006; van Zyl & Claeyé, 2019; Wallace et al., 2006). In addition, some studies in the literature emphasize that the pressure to present adequate results to donors may also reduce the NGO's transparency in reporting failures and undesired results, and thus its ability to learn and be more effective (Agyemang et al., 2009; Ebrahim, 2003b; O'Dwyer & Unerman, 2007; Schmitz et al., 2012; van Zyl & Claeyé, 2019).

2.2 Accountability “for what”

Regarding for what the NGO is responsible for, although financial issues primarily define accountability in business firms, NGO accountability focuses more on whether they make proper use of their financial resources, that is, how they perform their social work and what are the results they achieve in trying to accomplish those goals (Ebrahim, 2003b; Ebrahim et al., 2014; Fremont-Smith, 2004; Hansmann, 1996; Moore, 2000; Saxton et al., 2014).

Distinguishing between the dimensions of financial accountability and performance accountability is thus critical in NGO, as many scholars have identified (Avina, 1993; Brinkerhoff’s, 2001; Brody, 2002; Connolly & Hyndman, 2004; Cutt & Murray, 2000; Ebrahim 2003a; Edwards & Hulme, 1996; Frumkin, 2006; Goodin, 2003; McDonnell & Rutherford, 2018; Najam, 1996; O’Dwyer & Unerman, 2007; Saxton & Guo, 2011). Financial accountability proves whether the NGO is accountable for the money it raises from various sources, whereas performance accountability evaluates the results and impact of the NGO with respect to its goals and mission-driven objectives.

Although these two categories are well recognized in the literature, multiple definitions and differences in the concepts have made it difficult to consolidate a homogeneous concept of accountability for NGOs. All show consensus on the distinction between accountability for "finance" and accountability for "performance". Academics also consider performance accountability as more important for NGOs, since NGOs should be accountable to stakeholders not only for financial sustainability but also, and more importantly, for the social impact of their activities as defined in their mission. The reality may be different, however.

2.3 Accountability “how”

Accountability is the basic principle of responsible practice for any institution, public, private or NGO (Edwards & Fowler, 2002), but who is asking the NGO to be accountable. The NGO’s capability to satisfy the requirements of all its stakeholders depends on its ability to formulate accountability systems that account, both internally and externally, for dimensions of economic and social commitment. Due to the complexity of this accountability, NGOs need more complex mechanisms that include not only formal procedures but other more flexible processes that bring them closer to their stakeholders (Costa et al., 2011; Ebrahim, 2003a; Unerman & O’Dwyer, 2006). However, almost all of the accountability mechanisms used by NGOs are adaptations of those used by for-profit companies, which on the one hand, have the resources to complete reports, certifications, or codes of conduct, and on the other hand, financial results are usually enough to validate their performance.

3. METHODS AND MATERIAL

To identify the issues that have been addressed in accountability in NGOs, we adopted two methodological approaches: a systematic literature review and a bibliometric analysis. The source used to search for studies was the Web of Science Core Collection (WOS). WOS is frequently used by academics as it is a relevant database of abstracts and references for peer-reviewed publications in high impact journals (Harzing & Alakangas, 2016).

The bibliometric analysis was performed using the articles from SLR with VOSviewer software version 1.6.16 (0) (van Eck and Waltman, 2010) to facilitate visualization of the relationships between the proposed elements.

3.1 Systematic Literature Review

We defined our research criteria as NPO OR non-profit OR charity* OR NGO OR non-for-profit OR Nonprofit” to collect all nomenclatures used for these types of organization in the literature. We added the Boolean operator “AND” in the search string to associate these terms with “Accountability*,” so as to include all concepts related to “accountability” that could be queried. We added the “donor” or “stakeholder” terms with the Boolean operator AND to narrow the investigation to accountability to stakeholders. In a second query we changed the “donor” or “stakeholder” to “mechanism” to identify the articles related to accountability “how”. We applied all those terms to the "abstract" field to search for all English-language articles that treat the concept of NGO accountability to donors. The main research areas were related to Public Administration, Business Finance, Social Issues, Management, Economics and Social Work. The total search resulted in 226 articles of which 177 are related to accountability to stakeholders/donors and 49 to accountability mechanism.

We then examined all titles and abstracts of the articles and excluded those that were not related to accountability issues or were very specific to locations or organizations, that could limit or represent a bias in the identification of the research trends. After excluding those studies our sample for the systematic review included 134 articles. The studies date from 1995 to 2022. Out of the 134 articles identified, 37 used the term non-governmental organization and/or NGO, while the remaining articles used variations of the term nonprofit, including nonprofit organization (NPO), not-for-profit organization (NFP), charity, religious organizations and service club. Figure 1 details the selection and exclusion processes.

FIGURE 1. ARTICLE SELECTION AND KEYWORD DEFINITION

3.2 Bibliometric analysis

In order to refine the articles that address the topic of our study and to identify the key issues from the NGO donor accountability perspective and possible research gaps, we performed a co-ocurrence and bibliographic coupling bibliometric analysis using VOSviewer software version 1.6.16 (0) (van Eck & Waltman, 2010).

Keyword co-occurrence analysis shows the relationship between keywords that appear together in a recurring way in some parts of queried articles and in different articles. It detects how often those terms (keywords) are included in the sample and how close the two terms are, that is, the time they appear together in different articles. Bibliographic coupling examines the number of references that two articles have in common. If two articles cite a third, then the first two are bibliographically coupled. This means that, the more references they share, the more similar their research topic (Arroyo et al., 2022).

The interactions formed by the application of these techniques are presented in network maps. Graphically, each node represents a term (keyword or article, depending on the analysis) that belongs to a cluster. Larger nodes correspond to more significant terms than smaller nodes, and the closer one node is to another, the more related they are (even if the nodes are not in the same cluster). Finally, the lines show the links between nodes (Van Eck & Waltman, 2010).

4. RESULTS

4.1 Keywords occurrence

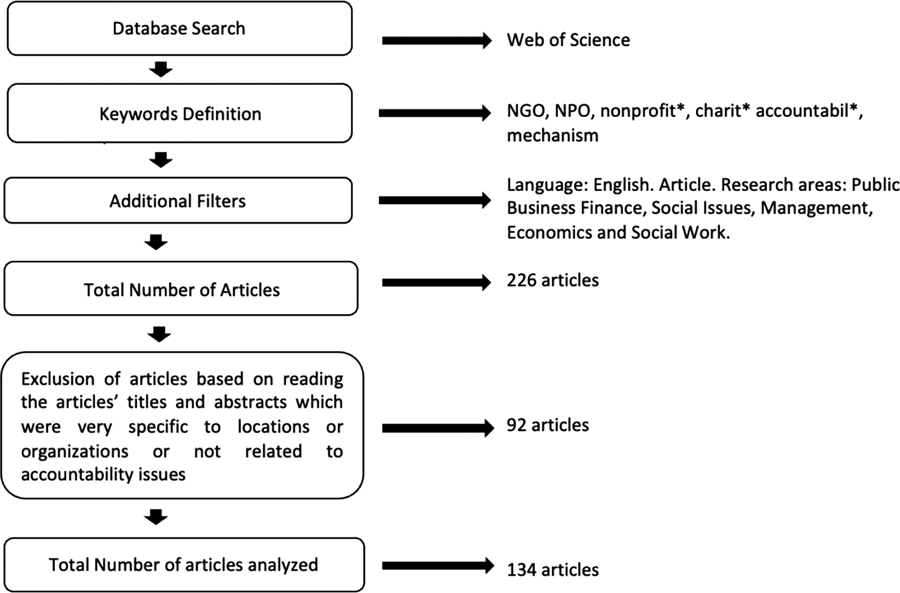

For the keywords co-ocurrence analysis we considered the keywords, provided by the authors, that occurred at least twice. Initially, there were a total of 381 keywords, of which 63 occurred at least twice. They were grouped in nine defined clusters all related to each other. Figure 2 shows the visualization map.

FIGURE 2. VOSVIEWER CO-OCCURRENCE OF TERMS MAP

In Cluster 1 (red), the terms financial reporting, compliance, disclosure, effectiveness and transparency appear together with the keywords charity, non-governmental organization, nonprofit organization and not-for-profit. The studies in this group address issues related to accountability “for what” topic by discussing the relevance of financial reporting and how the organizations disclosure them (Cordery et al., 2019; Keating & Frumkin, 2003). Articles in this cluster that include the term non-governmental also address the organization's transparency and reputation that could be established for its accountability (Gent et al., 2015).

Cluster 2 (green) groups accounting, beneficiary accountability, case study, education, regulation, stakeholders, along with ngo, non-profit and public sector. Studies in this group are associated with accountability “to whom” question considering the different needs in relation to accountability information of the different stakeholders (Cordery & Baskerville, 2011; Yesudhas, 2019) and how they respond to the accurate information provided by the organization (Feng et al., 2016) without distinction among NGO or NPO.

Cluster 3 (dark blue) includes development aid, downward accountability, felt accountability, felt responsibility, microenterprise, upward accountability, ngos and ngos accountability. Again, the main topic of this group is related to accountability “to whom” subject. In this cluster most of the articles refer to NGOs and discuss the problem regarding accountability to different stakeholders and the effects that prioritizing accountability to donors (upward accountability) produce on the organization (Dewi et al., 2019; Murtaza, 2012) suggesting solutions to balance the accountability to donors and beneficiaries (downward accountability) (Chu & Luke, 2022; O'Dwyer & Boomsma, 2015).

Cluster 4 (yellow) gathers, donors, financial accountability, perceptions, voluntary disclosure, nonprofit organizations and charities. Articles in this cluster discuss the issues of “to whom” the nonprofit should be accountable for. Different perspectives about the greater accountability to donors instead of beneficiaries in NGOs are discussed and recommendations are suggested to balance both (AbouAssi & Trent, 2016; Connolly & Hyndman, 2017; Goncharenko, 2021; Kingston et al., 2019; Uddin & Belal, 2019).

Cluster 5 (purple) presents evaluation, internal development, organizational learning, outcome measurement, performance measurement, reporting and nonprofits. This group of articles is related to the topic of accountability “how” and addresses the need to establish mechanisms and frameworks, especially those related to performance measurement that could help to organizations to strengthen the relationship with their beneficiaries (Benjamin, 2008; Dar, 2014).

Cluster 6 (blue) includes accountability, governance, mission, performance, stakeholder salience religious organization and nonprofit. In this group, the discussion is about how organizations are accountable and the mechanisms they use for presenting their results (Ebrahim, 2005) and the effect on donors in the case of NGOs (Goncharenko, 2019; Yasmin & Ghafram, 2019).

In Cluster 7 (orange) the terms instrumental accountability, legitimacy, self-regulation, transnational communities, nonprofit accountability, and nonprofit governance. The articles in this cluster address the need to establish mechanisms that help organizations to be accountable. Those who deal with NGOs raise the option of self-regulation as an accountability mechanism for NGOs (Burger, 2012; Deloffre, 2016) or even join voluntary accountability groups (Tremblay-Boier et al., 2016) to overcome the standard accountability mechanism.

Cluster 8 (brown) gather the terms civil society, fundraising, non-profit organization, social media, and stakeholder theory. This group addresses issues less related to the other clusters. The topics deliberated in this cluster refer to NGOs and its fundraising (Zhou, 2019) and the influence and relationship of NGOs with civil society (Harsh et al., 2010; Oppong, 2018).

Cluster 9 (pink) includes the terms social accounting, social capital, trust, non-governmental and organizations. In this group, the importance of accountability and the way in which it is presented is related to the trust that the donor places in the organization, named as charity, NGO or NPO (Guo et al., 2022; Hyndman & McConville, 2018; Yates et al., 2021).

4.2 Bibliographic coupling

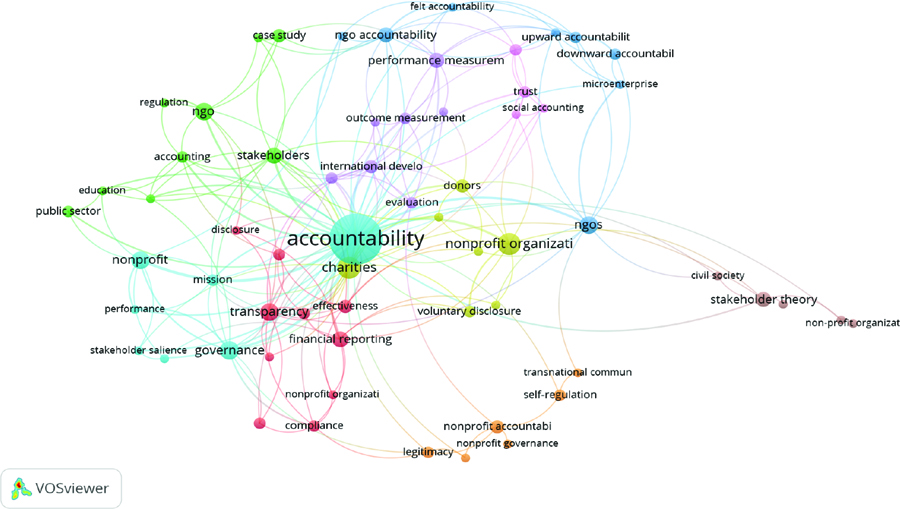

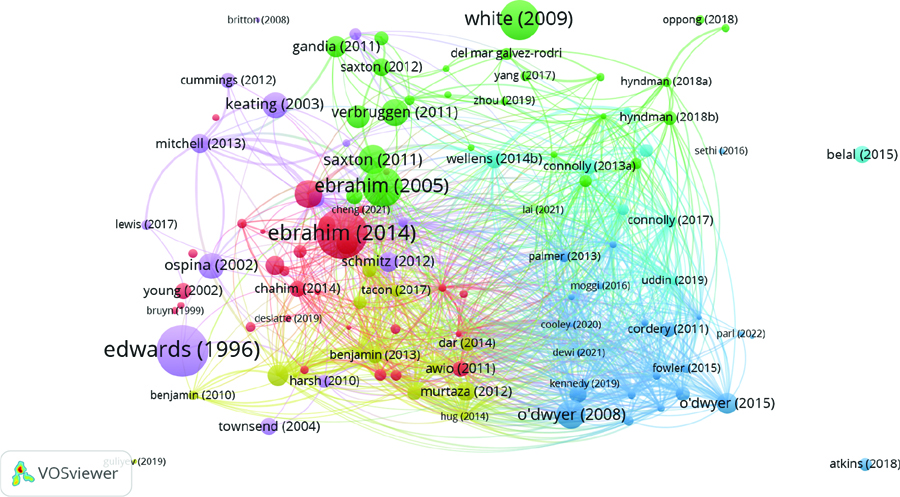

We selected bibliographic coupling by document with at least five shared references to guarantee the research topic is similar. Of a total of 134 articles, 114 of them shared at least 5 references and formed 6 cluster linked to each other. Figure 3 presents the visualization map generated.

FIGURE 3. VOSVIEWER BIBLIOGRAPHIC COUPLING MAP

The results found in bibliographic coupling are in line with the research avenues found in keyword analysis. Although in the case of keywords there is a greater number of clusters, since some articles are in more than one cluster due to they refer several keywords.

Articles in Cluster 1 (red) conceptualize about the challenge nonprofit accountability represents in relation to accountability “for what” and accountability to “whom” The articles explore accountability through social analysis of relationships between individuals enacted through social interaction, and options to improve the issues accountability represents (Ebrahim et al., 2014; Hielscher et al., 2017; Yates et al., 2021).

In cluster 2 (green) the authors address the relevance of NGO disclosures to NGO stakeholders. The studies analyze the effectiveness of NGO accountability and transparency disclosures—via social media, websites, or watchdog organizations—in attracting donations. Interestingly, different studies have found that donors often do not consult to watchdog ratings or NGO disclosures when making their donation decisions. Instead, they appear to assess the effectiveness and trustworthiness of NGOs through other means, such as familiarity, word of mouth, or the NGO's visibility in the community. The challenge thus seems to be to provide the information that users want, such as organizational effectiveness, not only use of funds the NGO received (Connolly & Hyndman, 2013; Gálvez-Rodriguez et al., 2016).

In Cluster 3 (dark blue) we found articles that study the effect of NGO performance and accountability on the NGO itself. Those articles discuss the negative effect of pressure on NGO performance measurement and accountability information on the NGO. The results seem to show that, the greater the pressure, the worse the NGO’s performance (Goncharenko, 2021; O’Dwyer & Boomsma, 2015). Analyzing the effect of volunteers on downward accountability, Dewi et al. (2019) observe that having volunteers can improve beneficiary accounting by reducing the distance between the NGO and its beneficiaries.

Most of the articles in Cluster 4 (yellow) examines accountability processes and mechanisms making distinction and clarifying the relationship between the accountability processes and the relationship with the different stakeholders. The topic of NGOs continuing to prioritize upwards accountability, despite NGOs’ intentions to change that trend is also revised (Benjamin, 2008; Murtaza, 2012; Yesudhas, 2019).

Analysis of the articles in each cluster shows that Cluster 5 (purple) gathers articles that primarily address regulation of NGOs’ financial disclosures as a means of improving accountability to donors. These articles discuss the importance of accreditation and regulatory compliance and the influence of NGOs’ organization and executives on that process. Heightened scrutiny of accountability, transparency, and ethical behavior are now part of the everyday language of NGO stakeholders. This scrutiny also enables NGOs to differentiate themselves from other NGOs and to strengthen their bonds with donors (Edwards & Hulme, 1996; Ospina et al., 2002; Schmitz et al., 2012).

Cluster 6 investigate the complexity of and the interaction between the accountability needs of the stakeholders in the context of nonprofit performance (Wellens & Jegers, 2014), the limited knowledge of the relative importance of different stakeholder and whether the information disclosed by the nonprofit meets their needs. Connolly & Hyndman (2017) also investigate the interaction between the accountability needs of donors and beneficiaries in the context of NGO performance. Despite the claims in the literature, they found that, upward accountability may facilitate the NGO’s downward accountability process.

5. DISCUSSION

In this section we analyze in depth the articles from the bibliometric analysis to identify NGOs peculiarities that may influence the NGO´s accountability from donor’s perspective and its main researchers. In order to do so, we assemble the articles according to the essential questions to whom the NGO is accountable; for what the NGO is responsible and how the information is provided.

Accountability to whom

Donors, through their monetary donations or volunteer work, provide the resources that NGOs have to do their work. This dependence on donor contributions influences the prioritization of NGOs' accountability towards them. Bias toward upward accountability affects not only the beneficiaries and their communities but also other types of relationships targeted by the NGO (Schmitz et al., 2012). Besides, the effect for that prioritization sometimes makes it difficult for NGOs to execute projects. Focusing on short-term issues to demonstrate results to donors makes it problematic to implement long-term projects that might be more relevant to their performance (Ebrahim, 2009; Christensen & Ebrahim, 2006; Ebrahim, 2003a; Edwards & Hulme, 1996; Kilby, 2006; Van Zyl & Claeyé, 2019; Wallace et al., 2006).

The accountability to donors implies that NGOs need to publish information for donors that could limit the possibility of making other types of reports that are also necessary to know the NGO. Such practice may introduce a certain bias by restraining the scope of failures and therefore concealing the need to be more effective (Agyemang et al., 2009; Burger & Owens, 2010; Ebrahim, 2003b; O’Dwyer & Unerman, 2007; Schmitz et al., 2012). Reports preparation for donors also incurs in a higher administration cost for the NGOs, which in turn impacts negatively on donors’ demand for low overhead cost (Calabrese, 2010; Cnaan et al., 2011; Dietz et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2016; Ito & Slatten, 2020).

In view of the criticism of prioritizing upward accountability, some authors have presented alternatives to improve NGOs’ accountability process. Hielscher et al. (2017) propose that accountability must be founded on a comprehensive governance approach that analyzes all relationships with NGO stakeholders. These authors show that improving accountability in NGOs requires identifying the underlying competence dilemma in the NGO and focusing on collective self-regulation as a solution. Agyemang et al. (2009), Edwards and Fowler (2002), Kilby (2006), O’Dwyer & Unerman (2010), and van Zyl and Claeyé (2019) propose that beneficiaries should participate in the NGO’s accountability process by establishing a dialogue with them to assess how their needs are being met. Ebrahim (2003a,b; 2005), Christensen and Ebrahim (2006), and Costa et al. (2011) propose that nonprofits’ accountability should be based on the organization’s mission. Such change could avoid the problems NGOs face in responding to upward accountability to donors and downward accountability to beneficiaries. It would save NGOs from the danger of making accountability relationships with donors primary, since NGOs should be firm in their mission and thus also in their commitment to beneficiaries. Schmitz et al. (2012) proposed that solution is to share more relevant information with the beneficiaries and be more transparent in the communications, without clearly specifying how this could be done.

In the more recent literature, other authors, seek to eliminate the negative bias in donor accountability. Connolly & Hyndman (2017) investigate the interaction between the accountability needs of donors and beneficiaries in the context of NGO performance. Despite the claims in the literature, they find that donors, while seen as prominent stakeholders in NGOs, cede power to beneficiaries. Accountability to donors, therefore, does not necessarily preclude accountability to beneficiaries. On the contrary, upward accountability may facilitate the NGO’s downward accountability process. Similarly, O'Dwyer & Unerman (2007) show that donors also want to help NGOs improve accountability to beneficiaries. Dewi et al. (2019) observe that having volunteers can improve beneficiary accountability by reducing the distance between the NGO and its beneficiaries. Options such a felt responsibility to beneficiaries, in line with the organization’s mission, has also been identified as a mediator to balance both upward and downward accountability (Chu & Luke, 2022; O'Dwyer & Boomsma, 2015). Although these ideas are not common in the literature, they certainly have interesting implications for overcoming the limitations posed by bottom-up responsibility in NGOs

Accountability for what

The earliest studies on this subject distinguish between short-term functional accountability, which accounts for the use of resources and immediate impact; and strategic accountability, which accounts for the impact of one NGO’s actions on other organizations and on the environment in general (Avina, 1993; Edwards & Hulme, 1996; Najam, 1996). Ebrahim (2003a) and O’Dwyer & Unerman (2007) follow this differentiation between functional and strategic accountability.

In a following study, Cutt and Murray (2000) defined procedural accountability, as a basic level common to all organizations, that includes the organization’s accomplishment of processes and procedures. The second level, consequential accountability, is explicitly related to achievement of organizational objectives according to their mission and operational methods. Based on these definitions, the authors establish that the NGO’s financial statements simply describe the various sources of funding the organization uses and provide information at the basic procedural level but do not determine the impact of executing NGOs’ programs (consequential accountability).

Continuing with the differentiation of two types of accountabilities, Saxton and Guo (2011) follow Brinkerhoff’s (2001), define accountability for finance as related to financial resources and accountability for performance which seeks to demonstrate performance, considering the NGO’s mission objectives. Accountability for performance involves demonstrating the NGO’s progress toward its goals and holding it accountable for the agreed-upon performance objectives and achievement of its mission.

Subsequent studies (Brody, 2002; Connolly & Hyndman, 2004; Frumkin, 2006; Goodin, 2003; McDonnell & Rutherford, 2018) persist in identify two types of accountabilities with the same differentiation between financial and performance accountability, denominated fiduciary accountability and performance accountability. Fiduciary accountability depends on the credit and trust that organizations deserve. Performance accountability has two sub-dimensions: process responsibility and substantive responsibility. The first sub-dimension refers to the NGO’s organization and management and the second to how the results of NGOs’ activities relate to their objectives.

In summary, although there is not a single classification, there is a consensus among the scholars that accountability “for what?” must distinguish between financial and performance results. Performance accountability is more relevant for NGOs since they should be accountable to donors and other stakeholders not only for financial sustainability but for the social impact of their activities as defined in their mission. However, although the most significant aspect of NGOs is how they accomplish their social mission, still financial accountability gets extra attention (Cordery et al., 2019; Keating & Frumkin, 2003).

Nevertheless, there are scholars who discuss the negative effect of pressure on NGO performance measurement and accountability information on the NGO. The results seem to show that, the greater the pressure, the worse the NGO’s performance. Ebrahim (2003a) disagrees with the assumption that the more rigorous the performance measurement, the better. The time required to measure performance means that other activities must be stopped or delayed, so this accountability represents an opportunity cost for the NGO. He thus proposes focusing on measures that are really relevant to the NGO, not measures that are countable. Such practice would focus the NGO’s work more closely on its beneficiaries, whose interest is not in being informed but in being served. O’Dwyer and Boomsma (2015) found that accountability was fading as government accountability requirements became stricter and more demanding. In addition, since literature has proven that donors do not rely on standard accountability information in their donation decision (Connolly & Hyndman, 2013; Gálvez-Rodriguez et al., 2016; McDougle & Handy; 2014; Saxton et al., 2012; Szper & Prakash, 2011), it seems counterintuitive to spend money on reports that donors are not going to use.

Finally, there is a less studied area in the NGOs accountability which is that it can help to build donors’ trust. Through the information that NGO disclosures, NGO can reinforce its legitimacy and transparency, standing out from other organizations and thus attract a greater number of donors (Gent et al., 2015; Goncharenko, 2019; Guo et al. 2022; Hyndman & McConville, 2018; Yates et al., 2021).

Accountability how

Ebrahim (2003a, 2005), defines accountability tools as instruments or techniques nonprofits use to show accountability. Tools include financial reports, disclosures, and performance evaluations, repeated over time, and aimed primarily at donors. Other tools that nonprofits use are management practices that strengthen an organization’s focus on its mission, that ensure that the institution's core values, and mission are upheld and respond to donor concerns. He also points out that nonprofits tend to focus more on short-term accountability, in part because of the push for accountability upwards, rather than for the more strategic, long-term processes that form the core of nonprofits activity.

In the case of NGO, accountability mechanisms are used primarily to show donors that financial resources were used as intended and that the NGO's actions achieved the expected impact (Ebrahim, 2003a; Najam, 1996; O'Dwyer & Unerman, 2007). Upward accountability makes NGOs more active in reporting, auditing, and monitoring activities to demonstrate their performance (Christensen & Ebrahim, 2006; van Zyl & Claeyé, 2019). No such clear mechanisms exist, however, to evaluate NGO performance.

To overcome this constraint some authors propose “self-regulation” as an accountability process that NGOs perform by developing standard codes of behavior and performance. Self-regulation aims, on the one hand, to improve the NGO’s image despite a public scandal and, on the other, to protect the NGO from particularly restrictive regulations (Schweitz, 2001). Although government oversight (especially through reporting) may be appropriate for building public trust, self-regulation serves as a mechanism thus improves accountability processes to donors, beneficiaries, and the NGO itself (Burger, 2012; Ebrahim, 2003a; Hielscher et al., 2017; Stoezer et al., 2021). Costa and Andreaus (2014) propose a conceptual model that provides a mechanism to assess both functional and strategic accountability, its effectiveness and efficiency, and to drive behavior through feedback and readjustment. Another proposal is to join accountability clubs that incorporate mechanisms that monitor compliance and help maintain the necessary standards for the organization (Gugerty, 2009; Tremblay-Boire et al., 2016; Yates et al., 2021). Murtaza (2012) and Yesudhas (2019) stress that, despite NGOs’ aspirations for more meaningful and integrated accountability, they prioritize accountability to boards and donors and provide weak accountability to communities. To change this practice, the authors recommend developing an accountability mechanism and practicing transparency to empower beneficiaries. They do not, however, specify clearly how this change could be achieved.

Yet it is not only the limitations implied by the current mechanisms for adequate accountability in NGOs. The reporting process and communication require, a higher number of NGO staff personal to perform the process and thus higher overhead costs. This requisite creates a contradiction, due to the need to report low administrative expenses, as some NGOs lack a decent infrastructure to prepare the reports. Small NGOs are barely able to function as organizations, let alone serve their beneficiaries (Calabrese, 2010; Cnaan et al., 2011; Dar, 2014; Ito & Slatten, 2020; Liket & Maas, 2015).

6. CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER RESEARCH

Although the nonprofit accountability field is receiving attention from academics, it is still difficult to fully understand as researchers use a multitude of similar, but different key concepts. The wide range and complexity of the different types of organizations that comprise this sector create major challenges in research. In addition, it is not easy to build on previous findings, given the widespread use of the term “nonprofit” no matter what type of organization/cause it refers to.

The aim of the article is to shed light on accountability issues, specifically in NGOs. As these organizations dedicate themselves to more sensitive causes in society, donors demand greater transparency and legitimacy than to other nonprofits. So, accountability is a very significant area in NGOs as it demonstrates to stakeholders how they make their decisions and what results they obtain. It also enables NGOs to strengthen their legitimacy by making their values and the objectives to which they are oriented public. Further, transparency in their actions will serve to attract more donors and thus improve their financing.

NGOs rely heavily on donors to do their work, so they tend to prioritize their upward accountability to justify how they use the money they receive from the donations. Donors primarily raise three basic dimensions of accountability “for what”: transparency and effectiveness, legitimacy and reliability, and performance. The transparency dimension addresses how the money is spent and whether is it used effectively. Legitimacy questions address the values of the NGO and its role in society. Measuring performance has to do not only with the services provided by the NGO but also with the quality of the services provided that the financial resources were used well (Ebrahim, 2003a; Goncharenko, 2019; Jordan, 2005; Keating & Frumkin, 2003; Songco, 2007).

However, our research has identified several boundaries in the process—and prioritization of—accountability to NGO donors, whatever their cause or size. Since donors will not give their support without results from the NGO, NGOs are pressured to present results in the short term. Complying with this pressure enables them to improve their reputation and attract donors but restrict their achieving more strategic objectives in the long term (Gent et al., 2015). It may cause NGOs to reduce their reporting of failures and undesirable results and thus limit their ability to learn and be more effective (Agyemang et al., 2009; Burger & Owens, 2010; Ebrahim, 2003b; Jacobs & Wilford, 2010; O'Dwyer & Unerman, 2007; Schmitz et al., 2012; van Zyl & Claeyé, 2019). Preparing presentations on reports and results generates higher administrative costs that works against the NGOs because they are required to have low overheads cost (Calabrese, 2010; Cnaan et al., 2011; Dietz et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2016; Ito & Slatten, 2020; Lecy & Searing, 2015; Liket & Maas, 2015). Moreover, such presentations incur in opportunity costs as resources are dedicated to the information task rather than to other activities more relevant to achieve the NGO's objectives.

Some academics revisits the constraints donors impose on NGO accountability and short-term results relative to the possibility of partnerships with NGOs. The fact that NGO accounting is dominated by external accountability for the funds received limited use of management accounting. It would, however, enable improvement of value for money in the NGO’s programs and therefore their effectiveness (Clerkin & Quinn, 2019; Hudock, 2000). AbouAssi and Trent (2016) argue that greater accountability to donors could also help NGOs better manage other types of institutional organizations that enable them to reduce dependency on their donors. Providing accountability information based on felt responsibility has also been considered to help regulate accountability among all NGO stakeholders, not just donors (Chu & Luke, 2022; O'Dwyer & Boomsma, 2015). Even some researchers are already finding advantages in upward accountability since demanding results from NGOs can be linked to NGO effectiveness. Donors are also more aware of the importance of accountability towards beneficiaries, as it shows how effective the NGO is in performing its task (Ebrahim, 2003a; Jacobs & Wilford, 2010; O'Dwyer & Unerman, 2007; Schmitz et al., 2012; van Zyl & Claeyé, 2019).

NGOs need accountability systems (“how”) to suit their organization and donors and help them accomplish their financial objectives while they work to achieve their ultimate goal. Those mechanisms should be geared toward answering questions about transparency and legitimacy as well as assessing the independence and reliability of the NGOs. Many scholars have been studying these accountability systems, both reviewing the financial accounting tools NGOs should use (Andreaus & Costa, 2014; Ebrahim, 2003a,b; Keating & Frumkin, 2003) and exploring downward accountability mechanisms (Jordan, 2007; O’Dwyer & Unerman, 2010; O’Leary, 2017). No such clear mechanisms exist, however, to evaluate NGO performance. Despite their usefulness, self-regulation (Burger, 2012; Hielscher et al., 2017; Stoezer et al., 2021) and participation (Ebrahim, 2003a) do not seem to be easy mechanisms to implement and standardize so they can be updated periodically and consulted.

Hence, our proposal for future lines of research is to continue investigating the processes and mechanisms of accountability to donors to overcome the limitations so that donor accountability serves as a tool for improvement in NGOs. We believe that appropriate, accurate accountability can become the indicator of NGOs’ quality and trust, not only enabling the NGO to demonstrate its transparency and legitimacy but transforming its accountability into a marketing tool by which donors can evaluate it and compare it with other NGOs. To achieve this goal, NGOs must meet information requirements from donors. They must enhance communication with donors by asking them the important issues on which they want to be informed. Donors might consider not only financial results but other issues, such as good governance, greater consistency with stated objectives, professional experience, and transparency in expenses. The information presented to donors would thus include issues related to the NGO’s performance, enabling it to improve accountability to its beneficiaries. Further, this information could help to ensure that the accountability mechanism developed for the donor also serves as a learning mechanism for the NGO. In addition, we consider it would be useful for NGOs to ask their donors not only what kind of information they want but how often they expect to receive it. In this way, NGOs would meet the donors' expectations of staying informed, stop making unnecessary reports, and reduce their administrative costs.

Other lines of research, related to the above, are to analyze whether more suitable accountability reduces the overhead cost of producing unnecessary reports. Despite the complexity of the sector, build an “accountability taxonomy” for NGOs that considers their cause, size, and geography will be very relevant to create a body of knowledge on which to advance future research on NGOs. Last, we suggest that investigate the effect of donor accountability on intention to donate is also very promising research avenue worth to investigate.

Finally, as with any study, our research is not exempt from limitations. First of all, there is a risk in biographical analysis of the bias that search engines can impose. However, we verified that the references included correspond to relevant articles in the literature and also consulted articles referenced in the most cited (snowball). Second, the NGOs addresses in the article are mainly devoted to development cause; thus, as suggested for future research, it would be interesting to consider NGOs that address different causes and some other factors, such as NGO size or whether an NGO is local or international, as these may impact on NGO accountability.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: María Jesús Ríos Romero and Elena Urquía-Grande. Methodology: María Jesús Ríos Romero, Elena Urquía-Grande and Carmen Abril. Data collection: María Jesús Ríos Romero. Data analysis: María Jesús Ríos Romero, Elena Urquía-Grande and Carmen Abril. Drafting-Preparation of original: María Jesús Ríos Romero. Drafting-Proof, reading and editing: Elena Urquía-Grande and Carmen Abril. Supervision: Elena Urquía-Grande and Carmen Abril.

FUNDING

This research has not received external funding.

REFERENCES

AbouAssi K. & Trent D. L. (2016). NGO Accountability from an NGO Perspective: Perceptions, Strategies, and Practices. Public Administration and Development, 36 (4), 283-296. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1764.

Agyemang, G., O’Dwyer, B., & Unerman, J. (2009). NGO accountability: retrospective and prospective academic contributions. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32 (8), 2353-2366. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-06-2018-3507.

Arroyo Esteban, S.; Urquía-Grande, E.; Martínez de Silva, A.; & Pérez-Estébanez, R. (2022) Big Data, Accounting and International Development: Trends and challenges. Management Letters / Cuadernos de Gestión 22 (1) 193-213. https://doi.org/10.5295/cdg.211513sa.

Andreaus, M., & Costa, E. (2014). Toward an integrated accountability model for nonprofit organizations. Advances in Public Interest Accounting, 17. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1041-706020140000017006.

Avina, J. (1993). The evolutionary life cycle of non-governmental development organizations. Public Administration and Development, 13 (5), 453-474. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.4230130502.

Bendell, J. (2006). Debating NGO Accountability. NGLS Development Dossier. Palais United Nations, New York NY 10017, United States.

Benjamin, L.M. (2008). Account space: How accountability requirements shape nonprofit practice. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 37 (2) 201-223 https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764007301288.

Bryce, H. J. (2006). Nonprofits as social capital and agents in the public policy process: toward a new paradigm. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 35, 311-318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764005283023.

Brinkerhoff, D. W. (2001). Taking account of accountability: a conceptual overview and strategic options. US Agency for International Development, Center for Democracy and Governance, Implementing Policy Change Project, Phase 2.

Brody, E. (2002). Accountability and public trust. In L. M. Salamon (Ed.). The state of nonprofit America (pp. 471-498). Washington, DC: Brookings Institute. ISBN: 9780815724360.

Brown, J., & Dillard, J. (2015). Dialogic Accountings for Stakeholders: On Opening Up and Closing Down Participatory Governance. Journal of Management Studies, 52 (7), 961-982. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12153.

Burger, R. (2012). Reconsidering the Case for Enhancing Accountability via Regulation. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23 (1), 85-108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-011-9238-9.

Burger, R., & Owens, T. (2010). Promoting Transparency in the NGO Sector: Examining the Availability and Reliability of Self-Reported Data. World Development, 38 (9), 1263-1277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.12.018.

Calabrese, T. D. (2010). Public mandates, market monitoring, and nonprofit financial disclosures. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 30, 71-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2010.09.007.

Christensen, R. A., & Ebrahim, A. (2006). How does accountability affect mission?. The case of a nonprofit serving immigrants and refugees. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 17 (2), 195-209. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.143.

Chu, V., & Luke, B. (2022). "Felt responsibility": a mediator for balancing NGOs' upward and downward accountability. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 18 (2). 260-285. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-05-2020-0057.

Clerkin B., & Quinn M. (2019). Restricted Funding: Restricting Development? Voluntas, 30 (6), 1348-1364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-00048-6.

Cnaan, R. A., Jones, K., Dickin A., & Salomon, M. (2011). Nonprofit watchdogs: o they serve the average donor?. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 21 (4), 381-397. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.20032.

Connolly, C., & Hyndman, N. (2004). Performance reporting: a comparative study of British and Irish charities. British Accounting Review, 36 (2), 127-154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2003.10.004.

Connolly, C., & Hyndman, (2013). Towards Charity Accountability: Narrowing the gap between provision and needs?. Public Management Review, 15 (7), 945-968. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2012.757349.

Connolly, C., & Hyndman, (2017). The donor–beneficiary charity accountability paradox: a tale of two stakeholders. Public Money & Management, 37 (3), 157-164. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2017.1281629.

Cordery, C. J., & Baskerville, R. F. (2011). Charity transgressions, trust and accountability. VOLUNTAS, 22 (2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-010-9132-x.

Cordery, C. J., Crawford, L., Breen, O. B., & Morgan, G. G. (2019). International practices, beliefs and values in not-for-profit financial reporting. Accounting Forum, 43(1), 16–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2019.1589906.

Costa, E., Ramus, T., & Andreaus, M. (2011). Accountability as a managerial tool in non-profit organizations: evidence from Italian CSVs. Voluntas 22, 470-493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-011-9183-7.

Cutt, J., & Murray, V. (2000). Accountability and effectiveness evaluation in non-profit organizations. Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203461365.

Dar, S. (2014). Hybrid accountabilities: When western and non-western accountabilities collide. Human Relations, 67 (2) 131-151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713479620.

Deloffre, M.Z. & Maryam, Z. (2016). Global accountability communities: NGO self-regulation in the humanitarian sector. Review of International Studies, 42 (4) 724-747. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210515000601.

Dewi, M. K., Manochin, M., & Belal, A. (2019). Marching with the volunteers: their role and impact on beneficiary accountability in an Indonesian NGO. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 32 (4), 1117-1145. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-10-2016-2727.

Dietz, N., Barber P., Lott, C., & Shelly, M. (2017). Exploring the relationship between state charitable solicitation regulations and fundraising performance. Nonprofit Policy Forum, 8 (2), 183-204. https://doi.org/10.1515/npf-2017-0009.

Ebrahim, A. (2003a). Accountability in practice mechanisms for NGOs. World Development, 31 (5), 813-829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00014-7.

Ebrahim, A. (2003b). Making sense of accountability: conceptual perspectives for northern and southern nonprofits. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 14 (2), 191-212. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.29.

Ebrahim, A. (2005). Accountability myopia: losing sight of organizational learning. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 34 (1), 56-58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764004269430.

Ebrahim, A. S. (2009). Placing the normative logics of accountability in “thick.” American Behavioral Scientist, 52 (6), 885-904. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764208327664.

Ebrahim, A. S. (2010). The many faces of nonprofit accountability. In D. 0. Renz & R. D. Herman (Eds.), The Jossey-Bass handbook of nonprofit leadership and management (3rd ed., pp. 101-124. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119176558.ch4.

Ebrahim, A. S., Battilana, J., & Mair, J. (2014). The governance of social enterprises: mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 34, 81-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2014.09.001.

Edwards, M., & Fowler, A. (2002). The Earthscan Reader on NGO Management. London: Earthscan. ISBN 9781853838484.

Edwards, M., & Hulme, D. (1996). Too close for comfort?. the impact of official aid on NGOs. World Development, 24 (6), 961-973. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00019-8.

Feng, N. C., Neely, D. G., & Slatten, L. A. D. (2016). Accountability Standards for Nonprofit Organizations: Do Organizations Benefit from Certification Programs?. International Journal of Public Administration, 39 (6), 470-479. https://doi.org//10.1080/01900692.2015.1023444.

Fremont-Smith, M. R. (2004). Governing nonprofit organizations: Federal and state law and regulations. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674030459.

Frumkin, P. (2006). Strategic giving: The art and science of philanthropy. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN-10: 0-226-26626-5.

Gálvez-Rodríguez, M. D. M., Caba-Pérez, C., & López-Godoy, M. (2016). Drivers of Twitter as a strategic communication tool for non-profit organizations. Internet Research, 26 (5), 1052-1071. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-07-2014-0188.

Gent, S. E., Crescenzi, M. J. C., Menninga, E. J., & Reid, L. (2015). The reputation trap of NGO accountability. International Theory, 7 (3), 426-423. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971915000159.

Goncharenko, G. (2019). The accountability of advocacy NGOs: insights from the online community of practice. Accounting Forum, 43 (1), 135-160. https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2019.1589901.

Goncharenko, G. (2021). The multiplicity of logics, trust, and interdependence in donor-imposed reporting practices in the nonprofit sector. Financial Accountability and Management, 37 (2), 124-141. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12241.

Goodin, R. E. (2003). Democratic accountability: the distinctiveness of the Third Sector. European Journal of Sociology, 44 (3), 359-396. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975603001322.

Gugerty, M. K. (2009). Signaling virtue: voluntary accountability programs among nonprofit organizations. Policy Sciences, 42, 243-273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-009-9085-3.

Guo, Z.Q., Hall, M., & Wiegmann, L (2022). Do accounting disclosures help or hinder individual donors' trust repair after negative events?. Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2021-5409.

Ha, Q.A., Pham, P.N.N., & Le, L.H. (2022). What facilitate people to do charity? The impact of brand anthropomorphism, brand familiarity and brand trust on charity support intention. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00331-1.

Hansmann, H. (1996). The ownership of enterprise. Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press, Cambridge. ISBN-10: 0674001710.

Harzing, A., & Alakangas, S. (2016). Google Scholar, Scopus and the Web of Science: A longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics, 106, 787–804. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1798-9.

Hielscher, S., Winkin, J., Crack, A., & Pies, I. (2017). Saving the moral capital of NGOs: identifying one-sided and many-sided social dilemmas in NGO accountability. Voluntas, 28 (4), 1562-1594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9807-z.

Harsh, M., Mbatia, P., Shrum, W. (2010). Accountability and inaction: NGOs and resource lodging in development. Development and Change, 41 (2), 253-278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2010.01641.x.

Hudock, A. C. (2000). NGO's seat at the donor table: enjoying the food or serving the dinner?. IDS Bulletin, 31 (3), 14-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2000.mp31003002.x.

Hyndman, N., & McConville, D. (2018). Making charity effectiveness transparent: Building a stakeholder-focussed framework of reporting. Financial Accountability & Management 34 (2) 133-147. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12148.

Ito, K., & Slatten, L. A. (2020). A path forward for advancing nonprofit ethics and accountability: voices from an independent sector study. Journal of Public and Nonprofit Affairs, 6 (2), 248-253. https://doi.org/10.20899/jpna.6.2.248-273.

Jacobs, A., & Wilford, R. (2010). Listen first: a pilot system for managing downward accountability in NGOs. Development in Practice, 20 (7), 797-811. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2010.508113.

Jordan, L. (2005). Mechanisms for NGO accountability. Research paper series No. 3, Global Public Policy Institute, Germany.

Jordan, L. (2007). A rights-based approach to accountability, in Ebrahim, A. and Weisband, E. (Eds), Global Accountabilities: Participation, Pluralism, and Public Ethics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 151-167. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-93996-4_44.

Kane, J. (2001). The politics of moral capital. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511490279.

Kearns, K. P. (1996). Managing for accountability: Preserving the public trust in public and nonprofit organizations. Wiley. ISBN: 978-0-787-90228-5.

Keating, E., & Frumkin, P. (2003). Reengineering nonprofit financial accountability: toward a more reliable foundation for regulation. Public Administration Review, 63 (1), 3-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00260.

Kilby, P. (2006). Accountability for empowerment: dilemmas facing non-governmental organizations. World Development, 34 (6), 951-963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.11.009.

Kingston, K., Furneaux, C., de Zwaan, L., & Alderman, L. (2019). From monologic to dialogic: accountability of nonprofit organisations on beneficiaries' terms. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 33 (2), 447-471. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-01-2019-3847.

Lecy, J. D., & Searing, E. A. M. (2015). Anatomy of the nonprofit starvation cycle: an analysis of falling overhead ratios in the nonprofit sector. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44 (3), 539-563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764014527175.

Liket, K. C., & Maas, K. (2015). Nonprofit organizational effectiveness. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44 (2), 268-296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764013510064.

Lindenberg, M., & Bryant, C. (2001). Going global: Transforming relief and development NGOS. Kumanrian Press, 2001. ISBN: 156549136X.

Lloyd, R. (2005). The Role of NGO Self-Regulation in Increasing Stakeholder Accountability. One World Trust, London.

McDonnell, D., & Rutherford, A.C. (2018). Promoting charity accountability: understanding disclosure of serious incidents. Accounting Forum, 43 (1), 42-61. https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2019.1589903.

McDougle, L. M., & Handy, F. (2014). The influence of information costs on donor decision making. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 24 (4), 465-485. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21105.

Moore, M. (2000). Managing for value: organizational strategy in for-profit, nonprofit, and governmental organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29 (1), 183-20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764000291S009.

Murtaza, N. (2012). Putting the lasts first: the case for community-focused and peer-managed NGO accountability mechanisms. Voluntas, 23 (1), 109-125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-011-9181-9.

Najam, A. (1996). NGO accountability: a conceptual framework. Development Policy Review, 14 (4), 339-354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.1996.tb00112.x.

Ospina, S., Diaz, W., & O’Sullivan, J. F. (2002). Negotiating accountability: managerial lessons from identity- based nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31 (1), 5-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764002311001.

O'Dwyer, B., & Boomsma, R. (2015). The co-construction of NGO accountability. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 28(1), 36-68. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-10-2013-1488.

O'Dwyer, B., & Unerman, J. (2007). From functional to social accountability: transforming the accountability relationship between funders and non-governmental development organizations. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20 (3), 446- 471. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570710748580.

O’Dwyer, B., & Unerman, J. (2010). Enhancing the role of accountability in promoting the rights of beneficiaries of development NGOs. Accounting and Business Research, 40 (5), 451-471. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2010.9995323.

O’Leary, S. (2017). Grassroots accountability promises in rights-based approaches to development: the role of transformative monitoring and evaluation in NGOs. Accounting Organizations and Society, 63, 21-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2016.06.002.

Oppong, N. (2018). Negotiating transparency: NGOs and contentious politics of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative in Ghana. Contemporary Social Science, 13 (1), 58-71. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2017.1394483.

Prakash, A., & Gugerty, M. K. (2010). Trust but verify? voluntary regulation programs in the nonprofit sector. Regulation & Governance, 4, 22-3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2009.01067.x.

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1992). In search of the non-profit sector I: the question of definitions. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and NonProfit Organizations, 3 (2), 125-151. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01397770.

Saxton, G. D., & Guo, C. (2011). Accountability online: understanding the web-based accountability practices of nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40 (2), 270-291. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764009341086.

Saxton G. D., Kuo J.-S., Ho Y. C. (2012). The determinants of voluntary financial disclosure by nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41 (6), 1051-1071. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011427597

Saxton, G. D., Neely, D. G., & Guo, C. (2014). Web disclosure and the market for charitable contributions. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 33 (2), 127-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2013.12.003.

Schmitz, H., Raggo, P., & Bruno-van Vijfeijken, T. (2012). Accountability of transnational NGOs: aspirations vs. practice. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41 (6), 1175-1194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011431165.

Schweitz, M. L. (2001). NGO network codes of conduct: accountability, principles and voice. Paper presented to the International Studies Association Annual Convention, Chicago IL.

Sloan, M. (2009). The effects of nonprofit accountability ratings on donor behavior. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38, 220-236. https://doi.org/10.1177/08997640083164.

Songco, D. A. (2007). The evolution of NGO accountability practices and their implications on Philippine NGOs. A literature review and options paper for the Philippine Council of NGO Certification.

Sowa, J., Selden, S., & Sandfort, J. (2004). No longer unmeasurable? a multidimensional integrated model of nonprofit organizational effectiveness. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33 (4), 711-728. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764004269146.

Stötzer, S., Martin, S., & Broidl, C. (2021). Using certifications to signal trustworthiness and reduce the perceived risk of donors: An exploratory investigation into the impact of charity labels. Journal of Nonprofit and Public Sector Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495142.2021.1954131.

Szper, R., & Prakash, A. (2011). Charity watchdogs and the limits of information-based regulation. Voluntas, 22 (1), 112-141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-010-9156-2.

Tremblay-Boire, J., Prakash, A., & Gugerty, M. K. (2016). Regulation by reputation: monitoring and sanctioning in nonprofit accountability clubs. Public Administration Review, 76 (5), 712-722. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12539.

Uddin, M., & Belal, A. (2019). Donors’ influence strategies and beneficiary accountability: an NGO case study. Accounting Forum, 43 (1), 113-134. https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2019.1589905.

Unerman, J., & O’Dwyer, B. (2006). On James Bond and the importance of NGO accountability. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 19 (3), 306-318. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513570610670316.

Urquía-Grande, E., Rautiainen, A., & Pérez-Estébanez, R. (2017). The effectiveness of rural versus urban nonprofit organizations in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Third World Quarterly, 38 (9), 2129-2142. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1322464.

Urquía-Grande, E., Pérez-Estébanez, R., & Alcaraz-Quiles,F.J. (2022) Impact of Non-Profit Organizations’ Accountability: Empirical evidence from the democratic Republic of Congo. World Development Perspectives, 28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2022.100462

Vakil, A. (1997). Confronting the Classification Problem: Toward a Taxonomy of NGOs. World Development, 25 (12), 2057-2070. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00098-3.

van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84 (2), 523-538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3.

van Zyl, H., & Claeyé, F. (2019). Up and Down, and Inside Out: Where do We Stand on NGO Accountability? European Journal of Development Research, 3, 604-3. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-018-0170-3.

Wallace, T., Bornstein, L., & Chapman, J. (2006). The Aid Chain: Coercion and Commitment in Development NGOs. ITDG Publishing Practical Action Publishing, The Schumacher Centre for Technology & Development, Bourton on Dunsmore, Rugby, Warwickshire, CV23 9QZ, United Kingdom. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2009.01594.x

Wellens, L., & Jegers, M. (2014). Beneficiary participation as an instrument of downward accountability: A multiple case study. European Management Journal, 32 (6), 938-949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2014.03.004.

Yasmin, S., & Ghafran, C. (2019). The problematics of accountability: Internal responses to external pressures in exposed. Critical perspectives of accounting, 64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2019.01.002.

Yates, D., Belal, A. R., Gebreiter, F., & Lowe, A. (2021). Trust, accountability and ‘the Other’ within the charitable context: U.K. service clubs and grant-making activity. Financial Accountability and Management, 37 (4), 419-439. https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12281.

Yesudhas, R. (2019). Towards an era of official (involuntary) accountability of NGOs in India. Development in Practice, 29 (1), 122-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2018.1529141.

Zhou, H.Q. & Ye, S.H. (2019). Legitimacy, Worthiness, and Social Network: An Empirical Study of the key Factors Influencing Crowdfunding Outcomes for Nonprofit Projects. VOLUNTAS 30 (4) 849-864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-0004-0.

_______________________________

*Autora de correspondencia: mrios05@ucm.es

1ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1245-9084