TYPES OF EDUCATIONAL VIDEOS AND USAGE PATTERNS IN TEACHING QUANTITATIVE METHODS: AN EMPIRICAL STUDY

TIPOS DE VÍDEOS EDUCATIVOS Y PATRONES DE USO EN LA ASIGNATURA MÉTODOS CUANTITATIVOS: UN ESTUDIO EMPÍRICO

Beatriz Minguela-Rata (Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, España)*1

José Luis Arroyo-Barrigüete (Universidad Pontificia Comillas, Madrid, España)2

José Ignacio López-Sánchez (Universidad CEU San Pablo, Madrid, España)3

Carlos Martínez de Ibarreta (Universidad Pontificia Comillas, Madrid, España)4

Antonio Rodríguez-Duarte (Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, España)5

Abstract

This research analyzes the impact of the screencast typology (theory, software practice, problems) of educational videos in higher education on the pattern of use. For this purpose, the use of 21 educational videos on Quantitative Methods by a cohort of 398 students has been analyzed. Using a panel data model and controlling for several confounding factors, the results suggest that students use the videos mainly for exam preparation, and they prefer theory videos, despite knowing that the exams include exclusively problems and practice questions. It is also concluded that the perceived usefulness seems to depend on the type of teaching, being much lower when face-to-face than when online. Interaction analyses further show that the effect of video duration varies depending on content and modality. These results have important implications for teaching when face-to-face teaching is not possible for reasons beyond our control (pandemics, meteorological phenomena of high social impact such as floods and extreme snowfalls in Spain, winter storms in the USA, etc.).

Keywords: teaching, higher education, educational videos, use patterns.

JEL Codes: a22

Resumen

Esta investigación analiza el impacto de la tipología de los vídeos educativos en educación superior (teoría, prácticas de software y problemas) en su patrón de uso. Para ello, se ha analizado el uso de 21 vídeos educativos en la asignatura Métodos Cuantitativos por parte de una cohorte de 398 estudiantes. Utilizando un modelo de datos de panel y controlando varios factores de confusión, los resultados sugieren que los estudiantes utilizan los vídeos principalmente para la preparación de exámenes, y que prefieren los vídeos de teoría, a pesar de saber que los exámenes incluyen exclusivamente problemas y preguntas de práctica. También se concluye que la utilidad percibida parece depender del tipo de enseñanza, siendo mucho menor cuando es presencial que cuando es online. El análisis de interacciones muestra además que el efecto de la duración de los vídeos varía según el contenido y la modalidad de enseñanza. Estos resultados tienen importantes implicaciones para la docencia, especialmente cuando la enseñanza presencial no es posible por motivos ajenos a nuestra voluntad (pandemias, fenómenos meteorológicos de gran impacto social como inundaciones y nevadas extremas en España, tormentas invernales en EEUU, etc.).

Palabras clave: docencia, educación superior, videos educativos, patrones de uso.

Códigos JEL: A22

1. INTRODUCTION

The use of digital platforms for teaching and learning, also referred to as “digital pedagogy” was found to be a very useful technique to prevent contagions resulting from the pandemic caused by Covid-19 (Naidoo, 2020), especially in higher education (Anderson, 2020; Watermeyer et al., 2021). The pandemic highlighted the vulnerabilities of higher education and the need for a change in the education system (Aljanazrah et al., 2022; Watermeyer et al., 2021) with the aim of implementing new, flexible, and digital teaching and learning methodologies (Santoveña-Casal & Lopez, 2024). A key aspect of digital pedagogy is the use of digital environments and Information and Communication Technologies (Howell & MacMaster, 2022; Meléndez Rivera et al., 2022; Suárez-Guerrero et al., 2024), or as Suárez-Guerrero (2023) indicates, connecting technological opportunities with learning in teaching contexts. In this regard, Volkova et al. (2021) note that digital pedagogy is a kind of pedagogy that utilizes modern digital technologies to achieve better educational outcomes and, consequently, ensure a higher quality of education. This implies that the teacher should introduce changes in the traditional way of teaching (Meléndez-Rivera et al., 2022).

Among flexible digital technologies, educational videos stand out. Their use in higher education—whether as a substitute or complement to face-to-face teaching—peaked during the Covid-19 pandemic. Videos enable anytime, anywhere learning, reducing the need for ubiquity between teacher and student (Santoveña-Casal & López, 2024). Initially, it seemed that its use would be reduced once the pandemic was over. However, the frequent meteorological phenomena of high social impact (floods and extreme snowfalls such as those that occurred in Spain, or winter storms in the USA, among others) together with the growing number of online and streaming courses, have sustained the continued use of these teaching tools. In some cases, their use has even become essential.

Prior literature includes numerous studies on the use of educational videos (Oliveira et al., 2019). Many of them report that the availability of such resources is generally perceived positively by students (Bravo et al., 2011; Copley, 2007; Henderson et al., 2017; Morris et al., 2019; O’Callaghan et al., 2017). Other research suggests that videos contribute to improving student learning (Santos Espino et al., 2020). However, the impact of these didactic resources on academic performance remains unclear (Heilesen, 2010; He et al., 2012; O’Callaghan et al., 2017; Wieling & Hofman, 2010; Yousef et al., 2014), as makes the question of whether video type (theory, software practice, or problems) influences usage patterns.

Due to this lack of consensus, the aim of this paper is twofold: first, to examine whether the use of videos by students is appropriate; and second, to analyse how the type of educational video (theory, software practice, or problems) influences usage patterns. It is important to note that, in this study, students play an essentially passive role, as they are limited to viewing the material (scrolling, pausing, or rewinding) to grasp the ideas (Barbero et al., 2024). As this is an asynchronous activity, it increases students’ flexibility in organising their study time (Rodríguez Santos & Casado García-Hirschfeld, 2024).

To achieve this purpose, a set of 21 videos of different typology (theory, software practice or problems) were developed as a complement to face-to-face teaching during the 2019-2020 academic year. In this period, the face-to-face classes were cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but remained online. The aim was to examine whether there are differences in usage patterns of these videos (measured by total viewing time, number of accesses and coverage) as a result of the change in the teaching modality. In this sense, throughout the manuscript the term “coverage” will refer specifically to percentage of watch time from the total video), while “engagement” will be used for broader conceptual discussions (overall interaction)

The paper has been structured as follows. First, a section of theoretical background is presented. Then, the methodology used is detailed, including a description of the participants and the videos used. Next, the results obtained are shown, comparing them with the conclusions of previous research. Finally, the conclusions, limitations, and their implications for teaching practice are described.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Learning is the process of acquiring knowledge, skills, or abilities through study, experience, or teaching, resulting in improved performance. and new competencies and attitudes (Romo Aliste et al., 2006). According to the learning styles model of Neurolinguistic Programming (O’Connor & Seymour, 2001), each individual has a sensory preference that guides the way they learn. Three systems of mental representation can thus be identified: visual, auditory, and kinesthetic (VAK).

According to Romo Aliste et al. (2006), visual learners think in images, so they learn best when they read or see the information in some way, since they can absorb a large amount of information quickly. Auditory learners learn best when they receive explanations orally and when they can speak and explain that information to another person, but in a sequential and orderly manner. Finally, the kinesthetic system of representation is used when the body is put in motion through experiments, practical examples, projects, simulations, etc. This approach allows students to prefer practice and learning through experience and what they perceive.

Digital platforms for teaching and learning enable the delivery of content in multiple formats, suitable to diverse sensory preferences, including videos, podcasts, simulations, and more (Ali et al., 2018). Videos enable the reinforcement and verification of knowledge, transmitting information in an interactive and easy-to-absorb manner (Meléndez-Rivera et al., 2022). In addition, due to their intrinsic characteristics, they allow for matching visual and auditory learners, as well as to enhance kinesthetic learning by stimulating the learner to perform simulations.

In assessing the pedagogical value of video-based learning, Mayer’s Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (Mayer, 2005) provides a strong foundation for explaining why theoretical videos may resonate more deeply with students, even during practical exams where hands-on skills are being tested.

Mayer’s theory is built on three main assumptions: (1) Dual Channel Assumption: individual process information through two separate channels: visual and auditory; (2) Limited Capacity Assumption: each channel can only process a limited amount of information at a time; and (3) Active Processing Assumption: learners actively select, organize, and integrate information to build mental models. According to this theory, theoretical videos can feel more familiar because the multimodal delivery reinforces understanding: videos typically combine narration (auditory channel) and animations, images, or text (visual channel). Therefore, this dual coding helps learners form deeper connections between concepts, which could later be transferred to practical tasks.

A second argument under Mayer’s theory is that cognitive load can be better managed: well-designed theoretical videos follow principles such as segmenting (dividing information into meaningful units) and signalling (emphasizing key elements). These strategies help prevent cognitive overload, facilitating comprehension of complex ideas before practical application.

Regarding mental model construction, theoretical videos provide structured explanations that guide learners through the “why” and “how” of procedures. These mental models serve as internal roadmaps that students could follow, even when facing unfamiliar practical problems.

Another explanation relates to familiarity gained through repetition and consistency: students often rewatch these videos, which increases their comfort with the format. This familiarity reduces anxiety during assessments and boosts confidence even in practical exams.

Finally, the temporal flexibility feature of educational videos can enhance reflection: the pause–rewind–replay nature of videos allows students to reflect more deeply on theory, leading to better retention. This reflective learning is often overlooked in fast-paced hands-on environments.

Another theoretical framework that addresses the role of educational videos on learning performance is Sweller’s Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) (Sweller, 2016). CLT is a framework for analysing the effectiveness of video-based learning, particularly in terms of video length and learner engagement. This theoretical framework emphasizes how the human brain has a limited capacity for processing information, and how instructional design should aim to optimize that capacity. Sweller (2016) identifies three types of cognitive load: (1) Intrinsic Load: related to the complexity of the content itself; (2) Extraneous Load: caused by poor instructional design or distractions; and (3) Germane Load: cognitive effort devoted to processing and understanding the content. According to this framework, effective video-based instruction is expected to reduce extraneous load and supports germane load while managing intrinsic load depending on learner expertise.

Regarding video length, shorter videos are generally preferable because they minimise extraneous load. Long recordings often include digressions or excess narration that could overload attention and working memory, whereas concise, well-segmented videos are easier to process and reduce mental clutter. Shorter videos also help maintain an optimal germane load: when the length matches the learner’s ability, cognitive effort is directed towards comprehension rather than endurance, enabling better integration of new information with prior knowledge. Finally, shorter videos help prevent cognitive fatigue. Extended recordings may overwhelm working memory, leading learners to disengage or overlook key points.

In a similar way, educational video design is directly related to engagement: instructional clarity eventually enhances germane load, because a clear structure, logical flow, and visual aids help learners stay cognitively focused. Additionally, engagement grows when learners feel they’re making meaningful progress without confusion, reducing extraneous load through design. Simplifying design allows cognitive resources to be allocated to where they are most needed: concept comprehension, and videos that challenge students just enough (without overloading them) encourage deeper encoding of information. A recent work (Shen, 2024) shows that instructional videos within a flipped classroom setting could enhance student engagement in the learning process and improve learning outcomes.

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1986) also provides a framework for analysing the effectiveness of educational videos, particularly in examining how screencast typology influences students’ perceived usefulness, ease of use, and intention to use. Regarding perceived usefulness, theoretical screencasts may be considered more valuable for exam preparation, while software-practice videos may be appreciated for real-world application and skill development. With respect to perceived ease of use, short, well-segmented screencasts, especially those related to software practice and problems, can enhance usability, whereas familiar formats and consistent structures across typologies reduce friction. Finally, concerning behavioural intention to use, TAM helps explain why students tend to prefer certain screencast types (e.g., theory for revision and software for assignments).

Recent advances explore an integration of several of those frameworks, bridging the gap between traditional cognitive theories and cutting-edge AI technologies (Twabu, 2025). Other research lines incorporate the framework of students’ emotional self-efficacy profiles in relation to their academic performance in online learning contexts (Yu et al., 2022).

Therefore, according to these frameworks, it could be expected that a suitable design of educational videos would improve learning outcomes (Barut & Dursun, 2022; Mayer, 2021). However, as we mentioned earlier, the impact of these videos on academic performance and their usage pattern is unclear. For this reason, we analyse, on the one hand, whether the use of videos by students is appropriate, and on the other hand, the impact that the type of educational video (theory, software practice or problems) has on the pattern of use of these videos.

3. METHODS

From a methodological standpoint, this study focused on the analysis of digital trace data generated through the actual use of videos by a full cohort of students. This approach allowed us to capture observable behavioral patterns in a natural setting, without researcher intervention and free from the biases typically associated with self-reported data or memory-based accounts.

While we acknowledge the value that qualitative techniques—such as surveys, observation, or focus groups—could offer, the exceptional circumstances of the lockdown throughout much of the semester severely limited their feasibility. We decided not to administer online surveys, as we considered that the situation at the time could negatively affect both the response rate and the quality of the responses. This methodological choice was therefore deliberate and aimed at ensuring the internal validity of the analysis by relying on objective data. Nevertheless, future research could benefit from mixed-methods approaches that incorporate qualitative perspectives to further explore students’ perceptions and motivations.

3.1. Participants and videos

This study focused on the Quantitative Methods course for the Business Administration degree at the Universidad Pontificia Comillas (Spain), which during the 2019-2020 academic year, second semester, had a total of 398 students. At the beginning of the semester (January 13th 2020) 21 videos were developed, covering the entire contents of the subject, and whose purpose was to complement on-site classes. All videos were entirely designed and recorded by the same instructor, as Santos Espino et al. (2020) suggest, in higher education, instructor-generated videos strengthen the connections between faculty and students. Giannakos et al. (2016) concluded that videos on YouTube get a significantly higher number of hits than those on an institutional platform, so the first alternative was chosen, creating a specific channel. The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The videos are mostly of the “screencast” type, i.e. videos that “capture computer screen output with concurrent audio commentary” (Green et al, 2012: 717). All of them followed 3 out of 4 Brame’s (2016) recommendations to maximize coverage: use conversational language, speak relatively quickly and with enthusiasm, and package videos to emphasize relevance to the course in which they are used. The fourth recommendation, keep each video brief (6 minutes or less) has not been followed, as there is conflicting evidence regarding its impact on the use of videos, as will be discussed below. In addition, this allows us to test whether the length of the videos has an impact in this case.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of each video. As far as “Difficulty” is concerned, it was evaluated on a scale from 1 to 5 (1 being very easy and 5 being very difficult) based on the opinion of the instructors, taking into consideration the opinions of the students of other courses, and the results obtained by them in the exams. As far as “Typology” is concerned, 3 categories are considered: theory (videos in which the theoretical concepts of the subject are presented), software practice (software demonstration, in which the teacher uses the Gretl software to estimate and interpret econometric models), and problems (videos in which the instructor solves problems and exercises). As was indicated in the theoretical background, these three categories of videos align with visual and auditory learning styles and enhance kinesthetic learning.

TABLE 1. VIDEOS USED IN THE ANALYSIS

Name |

Upload date |

Duration (min:seq) |

Typology |

Difficulty (1-5) |

Video 1 Theory |

2020-Feb-4 |

8:40 |

Theory |

1 |

Video 2 Theory |

2019-Oct-24 |

11:09 |

Theory |

2 |

Video 3 Theory |

2019-Oct-24 |

18:47 |

Theory |

5 |

Video 4 Theory |

2019-Oct-24 |

6:31 |

Theory |

5 |

Video 5 Theory |

2019-Oct-24 |

11:23 |

Theory |

3 |

Video 6 Theory |

2019-Oct-19 |

18:39 |

Theory |

4 |

Video 7 Theory |

2019-Oct-19 |

7:31 |

Theory |

4 |

Video 8 Theory |

2019-Oct-19 |

14:06 |

Theory |

5 |

Video 9 Theory |

2020-Mar-11 |

14:03 |

Theory |

5 |

Video 10 Theory |

2019-Oct-19 |

15:20 |

Theory |

3 |

Video 11 Theory |

2020-Mar-11 |

27:51 |

Theory |

3 |

Video 12 Theory |

2019-Oct-19 |

8:29 |

Theory |

5 |

Video 13 Theory |

2020-Mar-27 |

24:53 |

Theory |

5 |

Video 14 Practice |

2019-Oct-24 |

23:47 |

Practice |

4 |

Video 15 Practice |

2019-Oct-24 |

10:32 |

Practice |

1 |

Video 16 Practice |

2019-Oct-24 |

13:22 |

Practice |

3 |

Video 17 Practice |

2020-Mar-24 |

8:36 |

Practice |

2 |

Video 18 Problems |

2020-Feb-29 |

24:34 |

Problems |

3 |

Video 19 Problems |

2020-Mar-11 |

23:55 |

Problems |

4 |

Video 20 Problems |

2020-Mar-24 |

13:03 |

Problems |

5 |

Video 21 Problems |

2020-Mar-24 |

7:27 |

Problems |

3 |

Source: Authors own work.

Although we did not collect self-reported data on students’ access to devices or internet quality, access to technology was not considered a limiting factor in this study. All students were required to have their own laptops in order to participate in mandatory in-class practical sessions using Gretl software. Furthermore, previous research confirms that the student body at this university has a generally medium-to-high or high socioeconomic profile (86% of fathers and 77% of mothers hold a university degree; Martínez de Ibarreta et al., 2010). Regarding student participation in the video views, the high number of views relative to the cohort size (398 students vs. a mean of 631.5 views per video), together with clear peaks around key academic milestones, suggests that most students accessed the videos at least once.

3.2. Data

For each video, three different daily metrics were calculated: total viewing time (hours that the video has been viewed), number of views (each time a learner opens a video), and normalized coverage time (percentage of watch time from the total video (Van der Meij, 2017)). In the case of the latter variable, some authors work with the median coverage (Bulathwela et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2014) and others with the mean (Wu et al., 2017). We have selected this second approach. We have considered the series from the beginning of the term (January 13th 2020) to the end of the classes (April 30th 2020).

All videos were hosted on YouTube, and the usage metrics (total watch time, number of views, and coverage) were extracted from YouTube Analytics. Although the platform does not allow identification of unique users or repeated views, it provides detailed daily aggregate data per video. While YouTube supports autoplay functionality, this feature depends on each user’s individual settings and is not something we could control. While autoplay may be a potential source of bias, we consider its likely impact on the results to be minimal, since sessions without user interaction are not counted as valid views and do not contribute to total watch time.

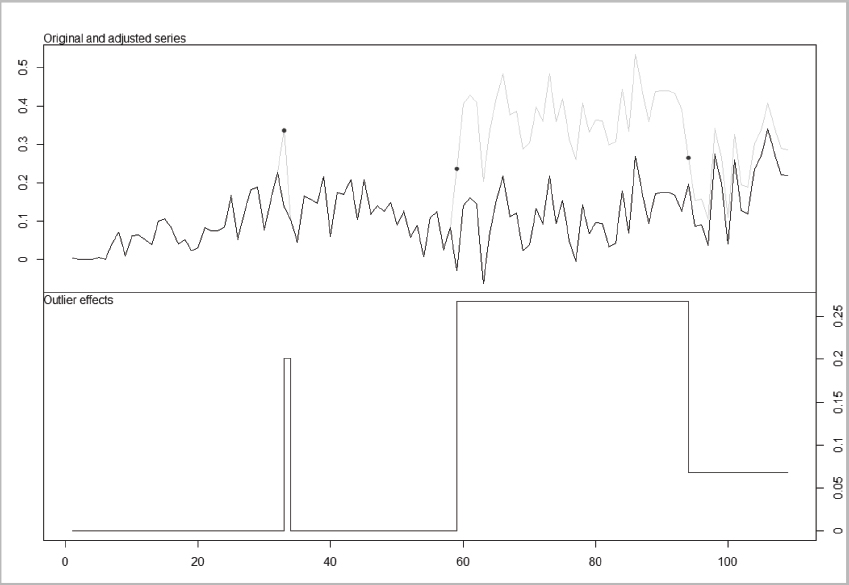

Figures 1, 2 and 3 display the aggregated data for the set of 21 videos, highlighting the outliers identified using the “tsoutliers” package (Lopez de Lacalle, 2019) in R (R Core Team, 2025). In all cases, some common patterns are observed. The first one is the presence of a level shift outlier on 11th March 2020 (t=59), the day following the suspension of face-to-face classes due to the Covid-19 pandemic. As noted above, although face-to-face classes were suspended, online classes were maintained on a relatively normal basis. However, the data indicated a significant reaction from students, who immediately increased the use of these videos after the announcement in a substantial way. The next common pattern is related to the second mid-term exam of the course, held on 15th April 2020 (t=94). Two days prior, there was a substantial increase in both viewing time and number of views, although coverage was not significantly affected. At the end of the test, we observed a sharp drop in all three metrics, with the presence of pronounced level shift outliers. This is an expected result, as the available evidence suggests that instructional videos are primarily used for exam preparation (Arroyo-Barrigüete et al., 2019; Brotherton & Abowd, 2004; Chester et al., 2011; Copley, 2007; D’Aquila et al., 2019; Giannakos et al., 2016).

FIGURE 1. DAILY VISUALIZATIONS (CONSIDERING ALL VIDEOS). IN THE GRAPHIC ABOVE, ORIGINAL SERIES IN LIGHT GRAY WITH DOTS, AND ADJUSTED SERIES AFTER REMOVAL OF OUTLIERS IN DARK GRAY. IN THE GRAPHIC BELOW, THE EFFECT OF OUTLIERS IS SHOWN

Source: Authors own work.

FIGURE 2. DAILY VISUALIZATION TIME MEASURED IN HOURS (CONSIDERING ALL VIDEOS). IN THE GRAPHIC ABOVE, ORIGINAL SERIES IN LIGHT GRAY WITH DOTS, AND ADJUSTED SERIES AFTER REMOVAL OF OUTLIERS IN DARK GRAY. IN THE GRAPHIC BELOW, THE EFFECT OF OUTLIERS IS SHOWN

Source: Authors own work.

FIGURE 3. DAILY AVERAGE COVERAGE (CONSIDERING ALL VIDEOS). IN THE GRAPHIC ABOVE, ORIGINAL SERIES IN LIGHT GRAY WITH DOTS, AND ADJUSTED SERIES AFTER REMOVAL OF OUTLIERS IN DARK GRAY. IN THE GRAPHIC BELOW, THE EFFECT OF OUTLIERS IS SHOWN

Source: Authors own work.

3.3. Variables

In order to carry out the analysis, it is necessary to control for several confounding factors identified in the literature, since as Poquet et al. (2018: 157) indicated that there are a “plethora of decisions to be made around learning with video” and that affect both their use and effectiveness. First, the duration of the video: Guo et al. (2014), after analyzing 6.9 million video watching sessions, conclude that video length was the most significant indicator of coverage. In fact, there seems to be a certain consensus in the literature for a greater acceptance of short videos (Bolliger et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2014; Meseguer-Martinez et al., 2017), despite some research suggests that students value full-lecture podcasts as highly as the short-summary podcasts, but the use is different, i.e. revision and review during exam preparation Vs to get a quick overview (Van Zanten et al., 2012). The work of Evans et al. (2016) on a set of 44 Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), detected no negative effects of increasing the length of the videos (which mostly ranged from 5 to 20 minutes in length). This study measured whether a student starts to watch or downloads a video, but it did not measure coverage as we have defined it in the current paper. These authors concluded that “video length […] is not a deterrent to students beginning to watch or download it” (Evans et al., 2016: 228). On the other hand, Lagerstrom et al. (2015) noted that the use of “watching sessions” may be leading us to misinterpret the effect of the duration of the videos, since many students had multiple watching sessions with each video, and when those sessions are stitched together, most students watched almost all of each video.

In relation to the second confounding variable, perceived level of difficulty, Newton & McCunn (2015) concluded that students’ use of videos, measured as number of accesses, is related to their perception of topic difficulty, although relationship is weak. This result is consistent with Ahn & Bir (2018) who found a direct relationship between perceived difficulty and the number of accesses, probably because “students needed to watch the videos multiple times to solidify their understanding of the concepts” (Ahn & Bir, 2018: 15). Similarly, Li et al. (2015) found that video sessions with a pattern of use compatible with higher perceived difficulty (such as the use of replay and frequent pauses) are more likely to be revisited. In this paper we have worked with the difficulty according to the criteria of the instructors of the subject, as a proxy of the difficulty perceived by the students. The evaluation was made on a scale from 1 (very easy) to 5 (very difficult). The score given to each video is based on the opinions expressed by students from previous years, as well as on the results obtained by them in the exams: certain topics are the ones that students tend to fail systematically.

A third factor to consider is the effect derived from midterm exams. As previously indicated, there is a broad consensus in the literature on the increased use of videos on the days prior to an evaluation. This pattern has also been observed in the data of this paper (see section 3.2. Data).

There are many other potential confounding factors, such as characteristics of the instructor who imparts the contents (Ozan & Ozarslan, 2016; Utz & Wolfers, 2020), discourse features (Atapattu & Falkner, 2018; Mayer et al., 2004; Mayer, 2008; Schworm & Stiller, 2012), instructors’ pointing gestures (Pi et al., 2019), language of instruction (same or different from the students’ native language), the style of production (Kizilcec et al., 2014; Kizilcec et al., 2015; Wang & Antonenko, 2017), use of subtitles6, existence of interactive questions in the videos (Geri et al., 2017), or the type of platform used to broadcast the videos (Giannakos et al., 2016), among others. Nevertheless, all of them are already controlled by the design of the experiment itself, as these variables are identical in all the videos.

In summary, many of the confusion factors identified in the literature are controlled by design, while others, such as the duration of the video, topic difficulty and temporal proximity to an assessment, must be controlled in the statistical analysis.

3.4. Econometric model

A panel data modelling approach has been followed. Each video is a cross-sectional unit. The general equation to be estimated is as follows:

here rit is the time, daily visualization, and coverage (three different models). X and T are, respectively, matrixes of video features and temporal features. αi capture specific unobserved characteristics of each video, whereas εit reflects the error or noise term. The estimation strategy will be the standard for panel data, which involves estimation by random effects and fixed effects. The Hausman test will determine the best strategy.

A significance level of 95% was chosen. Finally, and in relation to the typology of each video (theory, software practice and problems), we have differentiated according to the period: prior to the suspension of classroom-based classes (“classroom-based”) and during the suspension, a period in which the classes were online (“online”). The Theory classroom-based category has been chosen as the base level.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

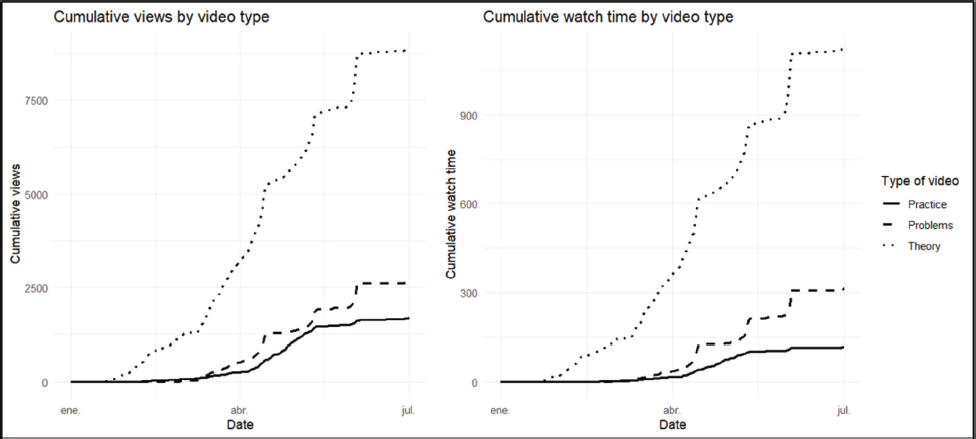

The graph of views and watch time by video type (Figure 4) seems to suggest a greater use of theory videos. However, since there are more videos of this type and their durations vary, no direct conclusions can be drawn from the graph.

FIGURE 4. CUMULATIVE VIEWS AND WATCH TIME BY VIDEO TYPE

Source: Authors own work.

Table 2 shows the results of the three models (time, visualizations and coverage), considering in all cases the same independent variables.

TABLE 2. PANEL DATA MODELS (N = 1,759 IN ALL MODELS)

Time |

Visualizations |

Coverage |

|||||||

Coef. |

Z |

P-Value |

Coef. |

z |

P-Value |

Coef. |

z |

P-Value |

|

Practice (classroom-based) |

-0.17 |

-2.4 |

0.016 |

-0.45 |

-2.17 |

0.030 |

-0.10 |

-2.19 |

0.029 |

Practice (online) |

0.03 |

0.44 |

0.658 |

0.58 |

2.77 |

0.006 |

0.07 |

1.55 |

0.122 |

Problems (classroom-based) |

-0.23 |

-3.59 |

<0.001 |

0.40 |

2.05 |

0.041 |

-0.06 |

-1.82 |

0.069 |

Problems (online) |

0.05 |

0.79 |

0.428 |

0.58 |

3.05 |

0.002 |

0.04 |

1.39 |

0.164 |

Theory (online) |

0.20 |

2.75 |

0.006 |

0.78 |

3.73 |

<0.001 |

0.17 |

5.62 |

<0.001 |

Duration |

0.98 |

6.37 |

<0.001 |

1.56 |

3.31 |

0.001 |

-0.18 |

-2.04 |

0.042 |

Difficulty |

0.00 |

0.24 |

0.811 |

-0.01 |

-0.28 |

0.779 |

-0.01 |

-0.96 |

0.337 |

Mid-term exam |

0.47 |

3.13 |

0.002 |

0.97 |

4.65 |

0.000 |

0.04 |

1.38 |

0.168 |

Constant |

-0.06 |

-0.86 |

0.391 |

0.37 |

1.76 |

0.078 |

0.22 |

5.32 |

<0.001 |

Sigma u |

0.09 |

0.29 |

0.06 |

||||||

Sigma e |

0.36 |

0.85 |

0.20 |

||||||

Rho |

0.06 |

0.11 |

0.08 |

||||||

Source: Authors own work.

Regarding the control variables, difficulty does not appear to have an impact on any of the metrics considered. This result is not in line with expectations, as previous literature concluded that there was a direct relationship between the number of accesses and perceived difficulty (Ahn & Bir, 2018; Li et al, 2015; Newton & McCunn, 2015).

An explanation could be that this study used difficulty ratings provided by professors rather than students’ own perceptions. The criteria applied by instructors and students might differ. Although this possibility could not be ruled out, it would seem less plausible given the experience of the instructors involved. Each video’s score was based on the collective teaching experience of several professors who know which topics students typically find more challenging (those that generate the most questions and correspond to the most frequently failed exam items). In this sample difficulty did not appear to affect viewing time, number of accesses, or coverage. Future research should replicate this analysis using students’ own difficulty ratings to test the robustness of these findings.

The dummy variable “midterm exam date” is significant and has a positive effect on viewing time and number of accesses. Consistent with previous research, video use increases in the days preceding an assessment (Arroyo-Barrigüete et al., 2019; Brotherton & Abowd, 2004; Chester et al., 2011; Copley, 2007; D’Aquila et al., 2019; Giannakos et al., 2016). On the other hand, coverage appears to be unaffected.

Regarding the third control variable, video duration, we observed a direct relationship with viewing time and the number of accesses, and an inverse relationship with respect to coverage. However, the latter effect was only marginally significant (p = 0.042). In summary, longer videos were accessed more frequently, but their coverage tended to decline slightly. This result aligns with the multiple “watching sessions” hypothesis put forward by Lagerstrom et al. (2015). Although none of the videos in this study exceed 28 minutes, indicating the absence of truly long recordings, the results suggest that as duration increases, students may prefer to view them in several shorter sessions. Hence, video length appears to shape patterns of use.

Additional analyses examined whether the effect of video duration differed by video type and delivery mode. First, we estimated a model that included all interaction terms between duration and video typology (namely, theory, practice, and problems videos, in both face-to-face and online contexts). Although no single interaction was significant, a joint Wald test indicated that they were collectively highly significant (p < 0.01), suggesting heterogeneous effects.

Next, we estimated models that added one interaction term at a time (Table 3). This approach revealed several significant and theoretically meaningful interactions. For instance, longer classroom-based practice videos were associated with more views but shorter viewing times. This result might indicate that students tended to click on these videos but abandon them earlier. In contrast, longer practice videos during the Covid-19 lockdown period (emergency remote teaching - ERT) were penalized across outcomes: they were viewed less frequently and had lower coverage. However, online problem-solving videos showed a positive effect of duration on the number of views. This result might reflect students’ greater reliance on worked examples when direct instructor guidance was unavailable.

TABLE 3. INTERACTION COEFFICIENTS FOR VIDEO DURATION BY TYPE/TEACHING MODALITY (SEPARATE MODELS FOR EACH INTERACTION TERM)

Time |

Visualizations |

Coverage |

|||||||

Coef. |

z |

P-Value |

Coef. |

z |

P-Value |

Coef. |

z |

P-Value |

|

Duration x Practice (classroom-based) |

-0.69 |

-2.87 |

0.004 |

1.71 |

3.95 |

<0.001 |

0.63 |

4.38 |

<0.001 |

Duration x Practice (online) |

0.38 |

1.51 |

0.130 |

-1.67 |

-3.50 |

<0.001 |

-0.61 |

-4.10 |

<0.001 |

Duration x Problems (classroom-based) |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

Duration x Problems (online) |

0.23 |

0.68 |

0.497 |

1.36 |

2.11 |

0.035 |

0.01 |

0.05 |

0.960 |

Duration x Theory (online) |

1.06 |

1.44 |

0.151 |

1.80 |

0.85 |

0.394 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

0.977 |

Note: Each coefficient in the table was estimated in a separate model including all main explanatory variables from the baseline specification. The interaction term between Duration and Problems (classroom-based) is not reported due to collinearity issues.

Source: Authors own work.

Coverage also varied. Longer classroom practice videos increased coverage, whereas longer online practice videos reduced it. These results might indicate that students engage with videos differently depending on their purpose, format, and learning context, particularly under ERT conditions.

Regarding the variable under study in the present paper, analysis revealed notable differences by video type. Additionally, the transition from face-to-face to online classes led to a substantial change in usage patterns.

During the face-to-face teaching period, software practice videos showed significantly lower usage than theory videos across all three metrics: they were accessed less often, viewed for shorter periods, and had lower coverage. This finding contrasts with Lin et al. (2016) and raises a paradox: both software practice and problem videos had been recorded at students’ own request. When this research project was designed, it was decided to conduct a pre-test (2018-2019), in which theory videos were produced. At the end of that course, students provided feedback, and based on their suggestions, additional problems and software practice videos were created. Despite being requested by students, these videos were used less than theory ones.

Perhaps the usefulness of this type of videos could be questioned if they are not accompanied by real practice. However, the available evidence suggests that software demonstration videos (such as the ones used in this paper) are effective for learning purposes. Van der Meij et al. (2018) tested three conditions on 82 elementary students from Demonstration-Based videos for software training: practice followed by video (practice-video), video followed by practice (video-practice), and video only. These authors concluded that students achieved significant learning gains and didn’t find evidence of the contribution of practice for learning. Thus, a possible explanation we can suggest is that perhaps students are less familiar with this type of videos, and therefore are more reluctant to use them, preferring the theory videos with which they are undoubtedly more familiar. Future research would benefit from incorporating data on students’ own perceptions.

On the other hand, during the online teaching period, the use of practice videos increased markedly. They reached the same levels as theory videos from the face-to-face period in terms of viewing time and coverage, and even surpassed them in the number of accesses. These results suggest that the transition to online classes led to a substantial rise in the use of this type of video.

Regarding the problem videos, we observed a different pattern. During the face-to-face teaching period, they were used less than theory videos in terms of viewing time, slightly more in number of accesses, and similarly in coverage. As in the case of practice videos, their use increased markedly during online classes, reaching the same level as theory videos from the face-to-face period in terms of viewing time and coverage, and exceeding them in the number of accesses.

The change from face-to-face to online classes led to an increase in theory video usage across all three metrics. This type of video was the most used by students. This finding was unexpected: previous evidence associates video use primarily with exam preparation, and the exams in this course were entirely practical, including only problem-solving and application questions. Therefore it is paradoxical that theory videos were most used, even though students knew in advance that the exam would focus on problems and practice.

There are several possible explanations for this result. First, students might feel more comfortable with theoretical videos because they resemble traditional lecture-based formats. This familiarity could make them perceive such videos as more useful, particularly in uncertain contexts such as ERT, perhaps because these videos are better suited to visual and auditory learners. Second, students might believe that mastering theoretical concepts is a prerequisite for successfully tackling practical problems. From this perspective, they view theory videos not as an alternative to practice but as a conceptual foundation that supports it. Finally, students’ study habits or time constraints might lead them to prioritize content they perceive as more essential.

Although these interpretations remain tentative, they underscore the need for qualitative research (interviews or focus groups) to gain a deeper understanding of the motivations and learning strategies underlying students’ video-use patterns.

5. CONCLUSIONS, IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The aim of this paper was (1) to examine whether the use of videos by students is appropriate and (2) to analyse how the type of educational video (theory, software practice, or problems) influences usage patterns.

To this end, we analysed a panel dataset describing the usage of 21 educational videos offered to a set of 398 students registered in the Quantitative Methods course at Universidad Pontificia Comillas (Spain) during the 2019-2020 academic year, while controlling for several confounding factors.

The analysis draws on a natural experiment: the abrupt suspension of face-to-face instruction due to the pandemic introduced an exogenous change in teaching conditions, dividing the semester into two comparable periods. Although the approach is primarily descriptive and exploratory, this quasi-experimental setting made it possible to identify variations in video-use patterns in response to the new instructional context. Since the analysis relies on real and non-intrusive data, it offers high ecological validity. Nevertheless, the results should be interpreted with caution: it is not possible to fully rule out the influence of unobserved factors or the presence of overlapping effects that are difficult to isolate in a natural setting.

Thus, in relation to the control variables, it is confirmed that on the days preceding an evaluation test, there is a substantial increase in video use. Students appear to consider this type of resource as a useful tool for exam preparation, a view shared by previous research (Brotherton & Abowd, 2004; Chester et al., 2011; Copley, 2007; D’Aquila et al., 2019; Giannakos et al., 2016). Contrary to several previous studies (Ahn & Bir, 2018; Li et al., 2015; Newton & McCunn, 2015), the difficulty of the topic covered in each video does not seem to affect its use, i.e., it does not affect viewing time, number of accesses, or coverage.

Regarding the length of the videos, longer videos tended to be viewed in multiple sessions, consistent with the findings of Lagerstrom et al. (2015), but this pattern did not negatively affect their overall use. The interaction analysis reinforces this observation, indicating that the impact of video length varies by type: while longer theory or problem videos may enhance usage, longer practice videos (particularly during the lockdown period) were associated with lower coverage and shorter viewing time.

The shift from face-to-face to online instruction produced a substantial increase in the use of all video types, leading to longer viewing times, more accesses, and higher coverage. It is worth noting that classes continued to operate in a similar way, with the only change being their online delivery. This finding suggests that students’ reliance on video resources differs markedly between instructional contexts. When teaching is face-to-face, students use videos far less than when learning occurs online.

In this course, students had access to numerous learning materials, including a textbook written by the teaching team, a complete set of theory slides, and an extensive collection of solved problems. Given this abundance of resources, the increased use of videos during remote instruction is particularly noteworthy. One possible explanation is that face-to-face classes provide students a greater sense of security, as the instructor is available to address difficulties in real time. When instruction moved online, this assurance might have diminished, leading students to perceive greater autonomy and a stronger need to manage their own learning, which in turn might have encouraged more intensive use of the available resources.

Examining how these perceptions vary according to prior experience with online or hybrid learning environments represents a promising avenue for future research. Moreover, the interaction effects observed here indicate that students’ responses to video characteristics, such as duration, differed significantly between face-to-face and remote periods, underscoring the critical role of context in shaping learning behaviour.

However, this conclusion should be interpreted cautiously, as the ‘online’ period corresponded to ERT caused by the abrupt suspension of face-to-face classes during the Covid-19 lockdown. This context presents an important limitation: it is not possible to determine with certainty whether the sharp increase in video usage during the second half of the course was solely due to the shift in teaching modality (face to face vs. online), or whether it was also amplified by the effects of the lockdown. The confinement led students to spend significantly more time in front of their devices, which might have facilitated greater access to the videos as a complement to online instruction. Therefore, while our results suggest that students perceived videos as more useful in the remote setting than in the face-to-face one, this finding should be viewed with caution, as it might be partially influenced by the exceptional constraints on mobility and daily life during the public health emergency.

Additionally, although we included control variables for perceived difficulty and proximity to the exam, we cannot fully rule out the possibility that some differences in video usage patterns reflect not only the shift from face to face to online teaching, but also potential differences in the perceived difficulty of the content covered during each period. It is also possible that the pattern of video usage in the second half of the course was partially influenced by increased academic pressure as the midterm exam approached. Although this factor was controlled for through a variable capturing proximity to the exam, we could not fully rule out that it had some effect on the rise in video views.

Finally, regarding video typology, the results indicate that theory videos were the most frequently used. This finding is surprising because the evaluation tests contained no theory questions (they focused entirely on problem solving and practice), and students were aware of this from the beginning of the course. Moreover, software practice and problem videos were added during the 2019–2020 academic year at the students’ own request. This unexpected result might reflect that students feel more comfortable with theory videos, as they are more familiar with them, possibly because their main learning channels are visual and/or auditory, and this type of video allows them to reinforce, verify, and assimilate knowledge more easily. Future research should include qualitative analyses, such as in-depth interviews with students, to better understand the reasons underlying this behaviour.

Therefore, this paper has important implications for teaching, especially for the design and use of this type of resources. Far from being considered a marginal teaching tool, the frequent meteorological phenomena of high social impact and the increase in the number of specialized online (and streaming) courses are causing their use to increase in recent times. Our findings suggest that students might not always engage with videos in ways that align with instructional goals. First, videos are mostly used for exam preparation rather than for studying the subject matter on an ongoing basis. Secondly, the sharp increase in usage during the online period suggests that students might have used the videos more as a substitute for face-to-face explanations than as a complementary resource. Finally, and perhaps most notably, students consistently engaged more with theory-oriented videos, even when these were not directly aligned with the contents evaluated in the exams. Interaction analyses further indicate that coverage with different video types is sensitive not only to content but also to design choices such as video length.

These patterns underscore the need to tailor video strategies to both pedagogical objectives and the instructional context. Therefore, it would be recommended that instructors offer more explicit guidance on how and when to use each type of video, particularly in relation to assessments and learning goals. To strengthen the impact of practical videos, these could be more effectively integrated by directly connecting them to specific classroom activities and by illustrating how they would help students develop the required skills. Encouraging active engagement, such as pausing the video and taking notes, could also enhance educational effectiveness.

However, this research has several limitations, the overcoming of which could involve the development of possible future lines of research. The analysis was conducted using data from the 2019-2020 academic year and focused on a single subject (Quantitative Methods), which limits the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the shift to online teaching was caused by an unexpected pandemic-related disruption, which may have influenced student behaviour in ways not fully captured by the data. In addition, although the study relied on expert-based assessments of topic difficulty, it would have been preferable to incorporate students’ perceived difficulty. Lastly, the absence of qualitative data limits our ability to explore the subjective reasons behind students’ usage patterns; future studies would benefit from combining behavioural data with surveys, interviews, or focus groups. It would also be valuable to examine how students perceive different types of videos in relation to their duration and instructional format, especially under emergency or hybrid teaching conditions. This would allow for a better understanding of the interaction between design features and learner engagement.

As future research, the analysis could be extended to other subjects of similar or even different content with the objective of assessing whether videos are used appropriately and whether changes in usage patterns are observed. In addition, longitudinal studies could help identify consistent behavioural trends across different cohorts and teaching modalities. Finally, it could be interesting to conduct in-depth interviews or surveys with students to better understand the reasons behind their preferences for certain types of videos, and to explore the design of integrated video models that combine theoretical explanations with interactive or applied practice, especially in hybrid learning environments.

FUNDING

This research has been partially funded by the Cátedra Santalucía of Analytics for Education.

CONTRIBUTION OF THE AUTHORS

Conceptualization: Arroyo-Barrigüete, Minguela-Rata, and Rodríguez-Duarte; Methodology: Arroyo-Barrigüete; Data collection: Arroyo-Barrigüete; Data analysis: Martínez de Ibarreta; Writing – original draft: all authors; Writing – review and editing: all authors; Supervision: Arroyo-Barrigüete and Minguela-Rata.

REFERENCES

Ahn, B., & Bir, D. D. (2018). Student Interactions with Online Videos in a Large Hybrid Mechanics of Materials Course. Advances in Engineering Education, 6(3), 1-24.

Ali, R., Uppal, M., & Gulliver, S. (2018). A conceptual framework highlighting e-learning implementation barriers. Information Technology & People, 31(1), 156-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.05.095

Aljanazrah, A., Yerousis, G., Hamed, G., & Khlaif, Z. N. (2022). Digital transformation in times of crisis: Challenges, attitudes, opportunities and lessons learned from students’ and faculty members’ perspectives. Frontiers in Education, 28(7), https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.1047035

Anderson, V. (2020). A Digital Pedagogy Pivot: Re-thinking higher education practice from an HRD perspective. Human Resource Development International, 23(4), 452–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2020.1778999

Arroyo-Barrigüete, J.L., López-Sánchez, J.I., Minguela-Rata, B., & Rodríguez-Duarte, A. (2019). Use patterns of educational videos: a quantitative study among university students. WPOM-Working Papers on Operations Management, 10(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.4995/wpom.v10i2.12625

Atapattu, T., & Falkner, K. (2018). Impact of lecturer’s discourse for students’ video engagement: Video learning analytics case study of moocs. Journal of Learning Analytics, 5(3), 182-197. https://doi.org/10.18608/jla.2018.53.12

Barbero, J., González, E. J., Lucena, J., Picatoste, X., & Rodríguez Crespo, E. (2024). La utilización del video como recurso de aprendizaje active en un entorno de aula invertida. Revista de Estudios Empresariales. Segunda Época, (1), 55-72. https://doi.org/10.17561/ree.n1.2024.8189

Barut Tugtekin, E., & Dursun, O. O. (2022). Effect of animated and interactive video variations on learners’ motivation in distance Education. Education and Information Technologies, 27(3), 3247-3276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10735-5

Bolliger, D. U., Supanakorn, S. & Boggs, C. (2010). Impact of podcasting on student motivation in the online learning environment. Computers & Education, 55(2), 714-722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.03.004

Brame, C. J. (2016). Effective educational videos: Principles and guidelines for maximizing student learning from video content. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(4), es6. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-03-0125

Bravo, E., Amante, B., Simo, P., Enache, M., & Fernandez, V. (2011, April). Video as a new teaching tool to increase student motivation. 2011 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 638-642). Amman, Jordan: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON.2011.5773205

Brotherton, J. A., & Abowd, G. D. (2004). Lessons learned from eClass: Assessing automated capture and access in the classroom. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 11(2), 121-155. https://doi.org/10.1145/1005361.1005362

Bulathwela, S., Pérez-Ortiz, M., Lipani, A., Yilmaz, E., & Shawe-Taylor, J. (2020). Predicting Engagement in Video Lectures. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.00592.

Chester, A., Buntine, A., Hammond, K., & Atkinson, L. (2011). Podcasting in education: Student attitudes, behaviour and self-efficacy. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 14(2), 236-247.

Copley, J. (2007). Audio and video podcasts of lectures for campus‐based students: production and evaluation of student use. Innovations in education and teaching international, 44(4), 387-399. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290701602805

D’Aquila, J. M, Wang, D., & Mattia, A. (2019). Are instructor generated YouTube videos effective in accounting classes? A study of student performance, engagement, motivation, and perception. Journal of Accounting Education, 47, 63-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccedu.2019.02.002

Davis, F. D. (1986). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results. Doctoral dissertation. MIT Sloan School of Management, Cambridge, MA.

Evans, B. J., Baker, R. B., & Dee, T. S. (2016). Persistence patterns in massive open online courses (MOOCs). The Journal of Higher Education, 87(2), 206-242. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2016.11777400

Geri, N., Winer, A., & Zaks, B. (2017). Challenging the six-minute myth of online video lectures: Can interactivity expand the attention span of learners? Online Journal of Applied Knowledge Management, 5(1), 101-111.

Giannakos, M. N., Jaccheri, L., & Krogstie, J. (2016). Exploring the relationship between video lecture usage patterns and students’ attitudes. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(6), 1259-1275. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12313

Green, K. R., Pinder-Grover, T., & Millunchick, J. M. (2012). Impact of screencast technology: Connecting the perception of usefulness and the reality of performance. Journal of Engineering Education, 101(4), 717–737. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2012.tb01126.x

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014, March). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@ scale conference (pp. 41-50). Atlanta, USA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556325.2566239

He, Y., Swenson, S., & Lents, N. (2012). Online video tutorials increase learning of difficult concepts in an undergraduate analytical chemistry course. Journal of chemical education, 89(9), 1128-1132. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed200685p

Heilesen, S. B. (2010). What is the academic efficacy of podcasting? Computers & Education, 55(3), 1063-1068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.05.002

Henderson, M., Selwyn, N., & Aston, R. (2017). What works and why? Student perceptions of ‘useful’digital technology in university teaching and learning. Studies in Higher Education, 42(8), 1567-1579. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1007946

Howell, J., & MacMaster, N. (2022). Teaching with technologies: Pedagogies for collaboration, communication, and creativity. Oxford University Press.

Kizilcec, R. F., Bailenson, J. N., & Gomez, C. J. (2015). The instructor’s face in video instruction: Evidence from two large-scale field studies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3), 724-739. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000013

Kizilcec, R. F., Papadopoulos, K., & Sritanyaratana, L. (2014). Showing face in video instruction: effects on information retention, visual attention, and affect. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (p. 2095-2102). Toronto, Canada: ACM SIGCHI. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556288.2557207

Lagerstrom, L., Johanes, P., & Ponsukcharoen, M. U. (2015, June). The myth of the six-minute rule: Student engagement with online videos. Paper presented at 2015 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Seattle, Washington. https://doi.org/10.18260/p.24895

Li, N., Kidziński, Ł., Jermann, P., & Dillenbourg, P. (2015, September). MOOC video interaction patterns: What do they tell us? In G. Conole, T. Klobučar, C. Rensing, J. Konert, & E. Lavoué (Eds.), Design for teaching and learning in a networked world: 10th European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning, EC-TEL 2015, Toledo, Spain, September 15–18, 2015, Proceedings (pp. 197–210). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24258-3_15

Lin, S. Y., Aiken, J. M., Seaton, D. T., Douglas, S. S., Greco, E. F., Thoms, B. D. & Schatz, M. F. (2016). Exploring university students’ engagement with online video lectures in a blended introductory mechanics course. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.03348.

López de Lacalle, J. (2019). tsoutliers: Detection of Outliers in Time Series. R package version 0.6-8. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tsoutliers

Martínez de Ibarreta, C., Rua, A., Redondo, R., Fabra, M. E., Nuñez, A., & Martín, M. J. (2010). Influencia del nivel educativo de los padres en el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes de la ADE. Un enfoque de género. In M. J. Mancebón Torrubia, D. Pérez Ximénez de Embún, J. M. Gómez Sancho & G. Giménez Esteban (Coords.), Investigaciones de Economía de la Educación Número 5 (1273-1296). AEDE, Asociación de Economía de la Educación.

Mayer, R. E. (2005). Cognitive theory of multimedia learning. In R.E. Mayer (Ed.) The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning, 31-48. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511816819.004

Mayer, R. E. (2008). Applying the science of learning: Evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. American Psychologist, 63(8), 760-769. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.63.63.8.760

Mayer, R. E. (2021). Evidence-Based Principles for How to Design Effective Instructional Videos. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 10(2), 229-240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2021.03.007

Mayer, R. E., Fennell, S., Farmer, L., & Campbell, J. (2004). A personalization effect in multimedia learning: Students learn better when words are in conversational style rather than formal style. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(2), 389–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.389

Mayer, R. E., Heiser, J., & Lonn, S. (2001). Cognitive constraints on multimedia learning: When presenting more material results in less understanding. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.187

Meléndez Rivera, M. S., Silva Rivera, M. P., Cortés Padilla, R., & Jaimes Estrada, O. J. (2022). “Retos y problemas en la pedagogía digital: Una experiencia desde la educación superior”, Revista Internacional de Estudios Sobre Sistemas Educativos, 3(13), 407-432.

Meseguer-Martinez, A., Ros-Galvez, A., & Rosa-Garcia, A. (2017). Satisfaction with online teaching videos: A quantitative approach. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 54(1), 62-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2016.1143859

Morris, N. P., Swinnerton, B., & Coop, T. (2019). Lecture recordings to support learning: A contested space between students and teachers. Computers & Education, 140, 103604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103604

Naidoo, J. (2020). Postgraduate mathematics education students’ experiences of using digital platforms for learning within the COVID-19 pandemic era. Pythagoras, 41(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.4102/pythagoras.v41i1.568

Newton, G., & McCunn, P. (2015). Student perception of topic difficulty: Lecture capture in higher education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(3), 252-262. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1681

O’Callaghan, F. V., Neumann, D. L., Jones, L., & Creed, P. A. (2017). The use of lecture recordings in higher education: A review of institutional, student, and lecturer issues. Education and Information Technologies, 22(1), 399-415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-015-9451-z

O’Connor, J., & Seymour, J. (2001). Programación Neurolingüística (PNL) para formadores. Barcelona, España, Editorial Urano.

Oliveira, L. R., Fontes, R., Collus, J., & Cerisier, J. F. (2019). Video and online learning in higher education: A bibliometric analysis of the open access scientific production, through Web of Science. In Proceedings of INTED2019 Conference (p. 8562-8567). Valencia, Spain. ISBN: 978-84-09-08619-1.

Ozan, O., & Ozarslan, Y. (2016). Video lecture watching behaviors of learners in online courses. Educational Media International, 53(1), 27-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2016.1189255

Pi, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhu, F., Xu, K., Yang, J., & Hu, W. (2019). Instructors’ pointing gestures improve learning regardless of their use of directed gaze in video lectures. Computers & Education, 128, 345-352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.10.006

Poquet, O., Lim, L., Mirriahi, N., & Dawson, S. (2018). Video and learning: a systematic review (2007--2017). Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge (p. 151-160). Sydney, Australia: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3170358.3170376

R Core Team (2025). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/

Rodríguez Santos, M. A., & Casado García-Hirschelfd, E. (2024). Aprendizaje basado en actividades asíncronas en un entorno blended learning. Revista de Estudios Empresariales. Segunda Época, (1), 5-18. https://doi.org/10.17561/ree.n1.2024.8202

Romo Aliste, M. E., López Real, D., & López Bravo, I. (2006). ¿Eres visual, auditivo o kinestésico? Estilos de aprendizaje desde el modelo de la Programación Neurolingüística (PNL)”, Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 38(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie3822664

Santos Espino, J. M., Afonso Suárez, M. D., & González-Henríquez, J. J. (2020). Video for teaching: classroom use, instructor self-production and teachers’ preferences in presentation format. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 29(2), 147-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2020.1726805

Santoveña-Casal, S., & López, S. R. (2024). Mapping of digital pedagogies in higher education. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 2437-2458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11888-1

Schworm, S., & Stiller, K. D. (2012). Does personalization matter? The role of social cues in instructional explanations. Intelligent Decision Technologies, 6(2). 105-111. https://doi.org/10.3233/IDT-2012-0127

Shen, Y. (2024). Examining the efficacies of instructor‐designed instructional videos in flipped classrooms on student engagement and learning outcomes: An empirical study. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(4), 1791-1805. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12987

Suárez-Guerrero, C. (2023). El reto de la pedagogía digital. Cuadernos de Pedagogía, 542, 9-13.

Suárez-Guerrero, C., Gutiérrez-Esteban, P., & Ayuso-Del puerto, D. (2024): Pedagogía digital. Revisión Sistemática del concepto, Teoría de la Educación. Revista Universitaria, 36(2), 157-178. https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.31721

Sweller, J. (2016). Cognitive Load Theory, Evolutionary Educational Psychology, and Instructional Design. In: Geary, D., Berch, D. (eds) Evolutionary Perspectives on Child Development and Education. Evolutionary Psychology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29986-0_12

Twabu, K. (2025). Enhancing the cognitive load theory and multimedia learning framework with AI insight. Discover Education, 4(160). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-025-00592-6

Utz, S., & Wolfers, L. N. (2020). How-to videos on YouTube: the role of the instructor. Information, Communication & Society, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1804984

Van der Meij, H. (2017). Reviews in instructional video. Computers & Education, 114, 164-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.07.002

Van der Meij, H., Rensink, I., & Van der Meij, J. (2018). Effects of practice with videos for software training. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 439-445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.029

Van der Zee, T., Admiraal, W., Paas, F., Saab, N., & Giesbers, B. (2017). Effects of subtitles, complexity, and language proficiency on learning from online education videos. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 29(1), 18-30. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000208

Van Zanten, R., Somogyi, S., & Curro, G. (2012). Purpose and preference in educational podcasting. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(1), 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01153.x

Volkova, L., Lizunova, I., & Komarova, I. (2021). Pedagogia digital: Problemas e soluçoes. Revista on line de Política e Gestao Educacional, 25(5), 3140-3152. https://doi.org/10.22633/rpge.v25iesp.5.16003

Wang, J., & Antonenko, P. D. (2017). Instructor presence in instructional video: Effects on visual attention, recall, and perceived learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 79-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.049

Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J. (2021). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: Afictions and afordances of emergency online migration. Higher Education, 81(1), 623–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

Wieling, M. B., & Hofman, W. H. A. (2010). The impact of online video lecture recordings and automated feedback on student performance. Computers & Education, 54(4), 992-998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.10.002

Wu, S., Rizoiu, M. A., & Xie, L. (2017). Beyond views: Measuring and predicting engagement in online videos. arXiv preprint arXiv:1709.02541.

Yousef, A. M. F., Chatti, M. A., & Schroeder, U. (2014). Video-based learning: a critical analysis of the research published in 2003-2013 and future visions. In eLmL 2014, The Sixth International Conference on Mobile, Hybrid, and On-line Learning (pp. 112–119). Barcelona, Spain: RIA XPS. ISBN: 978-1-61208-328-5.

Yu, J., Huang, C., He, T., Wang, X., & Zhang, L. (2022). Investigating students’ emotional self-efficacy profiles and their relations to self-regulation, motivation, and academic performance in online learning contexts: A person-centered approach. Education and Information Technologies, 27(8), 11715-11740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11099-0.

_______________________________

* Autor de correspondencia: minguela@ccee.ucm.es

1 ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7627-9165

2 ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3660-3933

3 ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4096-0992

4 ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4962-2401

5 ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7392-5683

6 Some works have reported that the use of text that duplicates words that are spoken in video have a detrimental effect, which is often referred to as the redundancy principle (Mayer et al., 2001). This would apply not only to the images shown but also to the use of subtitles. Nevertheless, a more recent work pointed out that “subtitles neither have a beneficial nor a detrimental effect on learning from educational videos” (Van der Zee et al., 2017).