Graph 1: Path of access to justice

Source: Various authors

Elaboration: The authors, 2019

EXPERIENCES OF ACCESS TO JUSTICE FOR PERSONS DEPRIVED OF LIBERTY IN ECUADOR

ANDRÉS DE JESÚS RAMÍREZ CHICA*

MARÍA ANTONIA MACHADO ARÉVALO**

Abstract: The Ecuadorian prison system has conditions that denotes a questionable validity of rights for inmates. In this context, access to justice (ATJ) is one of the most important rights to guarantee the rehabilitation of persons deprived of liberty (PDL) since confinement and the reality of the prison generate unique barriers for the ATJ. Through the analysis of in-depth semi-structured interviews, the ATJ experiences of the PDL and of actors linked to the social rehabilitation system are identified to state critical points in relation to the validity of this key right.

Keywords: persons deprived of liberty, human rights, access to justice, social rehabilitation system, prison crisis.

Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION. 1.1 Human Rights of the PDL. 1.2 Access to Justice. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS. 2.1 Preparation of the interview. 2.2 Population interviewed. 2.3 Collection and processing of information. 3. RESULTS. 3.1 Main problems that people deprived of liberty present in the path of access to justice. 3.2 Perception of the key actors linked to access to justice for PDL. 4. DISCUSSION 5. CONCLUSIONS.

1. INTRODUCTION

Persons deprived of liberty are a group of priority attention within Ecuadorian legislation due to the multiple vulnerabilities that they present and because their state of deprivation implies that their life depends on state protection. Despite this premise, the reality of the Ecuadorian prison system is far below the vital minimums established to guarantee a dignified life and achieve true social reintegration (Vera, 2019). In recent years, the historical problems in prisons at Ecuador have been exacerbated by the crisis in the prison system (Permanent Committee for the Defense of Human Rights, 2019) that has been dragging on for several years and that shows the weakness of the state institutional system to deal with criminality, the systematic violations of human rights towards persons deprived of liberty, the critical levels of overcrowding, the lack of alternatives for programmed recreation, formal and not formal education plus the constant budget reduction (Oña, 2021; Arrias, Plaza and Herráez, 2020); Undoubtedly this is a consequence of the primacy of punitive policies over preventive policies that Ecuador has continued to strengthen in recent years. (Cuesta, 2015; Núnez, 2006).

The Inter-American Association of Public Defenders (Asociación Interamericana de Defensorías Públicas) (2014) expresses that the situation in which many persons deprived of liberty are found in the region (Ibero-America) is critical due to - among other causes -, prison overcrowding, episodes of violence in prisons and the precariousness of the conditions of deprivation of liberty. The notable structural deficiencies of the detention centers and prison systems in the region are also mentioned. In addition, it refers that many people deprived of liberty come from areas of social exclusion, with a precarious economic situation and with their most basic needs not covered. Intriago Muñoz & Arrias Añez, (2020) argue that prison overcrowding causes other effects on the health and well-being of people living in these conditions and can also make social rehabilitation work difficult and lead to inhuman, cruel or degrading treatment. In the Ecuadorian case, according to Pazmiño (2011) a significant number of people deprived of liberty had another type of vulnerability, like be it economic, labor (before entering a detention center), health, gender, among others.

In this context, it is essential to make an analysis of the experiences of people deprived of liberty and regarding access to justice in the face of violations of their human rights by both the State and its agents, as well as other persons deprived of liberty; in addition to inquiring about the testimonies of the actors linked to the social rehabilitation system to determine the main problems to achieve the human right of access to justice by the PDL.

Studies in this area have made significant progress in accounting for the legal and regulatory frameworks that protect this right, however, there is still a theoretical gap about highlighting the personal experiences of the PDL and the vision of actors linked on the system about the main bottlenecks of access to justice that this path reveals to identify leverage points focused on the practical experiences of the actors and find solutions to the increasingly alarming crisis of the prison system.

Thus, this research investigates this issue from the case of “Turi” Social Rehabilitation Center (SRC), located in the southeast of Ecuador, in the city of Cuenca, considered the third most important city in the country, and which houses approximately 2,600 persons deprived of liberty from various areas of the country and from other latitudes due to its characteristic of a maximum security prison. The reality of this SRC is similar to that of other SRC in the country since because the social rehabilitation policy is exclusive to the National Social Rehabilitation System and is deconcentrated in the management of the localities, since there are the same guidelines for all SRC of the country in relation to budget allocation and management, programmatic axes, protocols, regulatory frameworks and assistance personnel. (National Social Rehabilitation System, 2020).

In addition, it is important to analyze the case of SRC Turi due to its most recent problems. On February 23, 2021, a series of riots in the 4 largest prisons in the country resulted in the death of 79 inmates. That, according to reports issued by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the Organization of American States, placed Ecuador on the list of the 10 main prison massacres that have historically been perpetrated in South America. Of the 79 deaths nationwide, SRC Turi registered the highest figure with 34 deaths. (El Comercio, 2021)

One of the cases that highlights the importance of access to justice as a tool for claiming violations of the rights of the PDL took place in the SRC Turi of the city of Cuenca. This case of abuse from the Unit for the Maintenance of Order (UMO by its acronym in Spanish) against those deprived of liberty on May 31, 2016. The incident occurred when several persons deprived of liberty were subjected to beatings and cruel treatment during a routine police procedure. The event was recorded and viralized by social networks. When the case was prosecuted, it was determined that there was a violation of human rights. The police abuse was perpetrated in a group of more than 200 victims, "however only 13 PDL took legal action, reflecting the fear and subordination that still exists in the social rehabilitation centers due to the presence of power relations." (Aguilar, 2017; p. IV)

In this order of ideas, the research will delve in the human rights of persons deprived of liberty and access to justice as central variables of analysis.

1.1 Human Rights of the PDL

People deprived of liberty are rights holders; however, González (2018) affirms that some PDL’s fundamental rights are restricted in order to safeguard public order and social harmony. That limitation is reduced to what is strictly provided in the conviction. Article 4 subsection 2 of the Criminal Code of Ecuador (COIP) establishes that “persons deprived of liberty retain ownership of their human rights with the limitations of the deprivation of liberty and shall be treated with respect for their dignity as human beings. Overcrowding is prohibited” (COIP, 2014).

The Organic Comprehensive Criminal Code of Ecuador (COIP by its acronym in Spanish) determines that persons deprived of liberty shall enjoy the rights and guarantees recognized in the Constitution of the Republic and international human rights instruments. In its text, it lists and develops the content of the rights of persons deprived of liberty:

• Right to physical, mental, moral and sexual integrity.

• Right to freedom of expression, to receive information, give opinions and disseminate them by any means available in the detention centers.

• Right to freedom of conscience and religion and to have it facilitated, including not professing any religion.

• Right to work, education, culture and recreation of persons deprived of liberty and guarantees the conditions for their exercise.

• Right to their personal and family privacy. The person deprived of liberty has the right that other people respect his private life and the private life of his/her family.

• Right to the protection of personal data, which includes the access and use of this information.

• Right to associate for lawful purposes and to appoint their representatives, in accordance with the Constitution of the Republic and the Law.

• Right to vote (suspended right for those who have a final conviction)

• Right to file complaints or petitions.

• Right to be informed, at the time of their admission to any detention center, in their own language about their rights, the rules of the establishment and the available resources to formulate petitions and complaints.

• Right to preventive, curative and rehabilitative health, both physical and mental, timely, specialized and comprehensive.

• Right to adequate nutrition, in terms of quality and quantity, in appropriate places for this purpose.

• Right to maintain their family and social ties. They must be located in deprivation of liberty centers close to their family, unless they express their contrary wishes or that, for duly justified security reasons or to avoid overcrowding, their relocation is necessary.

• Right to communicate with and receive visits from family and friends, from their public or private defender, and the intimate visit of their couple, in places and conditions that guarantee their privacy, the safety of people and the deprivation of liberty center.

• Right to regain his immediate freedom, when he completes his sentence, receives amnesty, pardon or the precautionary measure is revoked.

• Right to proportionality in the determination of disciplinary sanctions.

All these rights must be guaranteed in practice by the State so that it is possible to speak of effective social rehabilitation and respect for human dignity. However, as will be seen later, the reality in the prison context of Ecuador is far from that.

1.2 Access to Justice

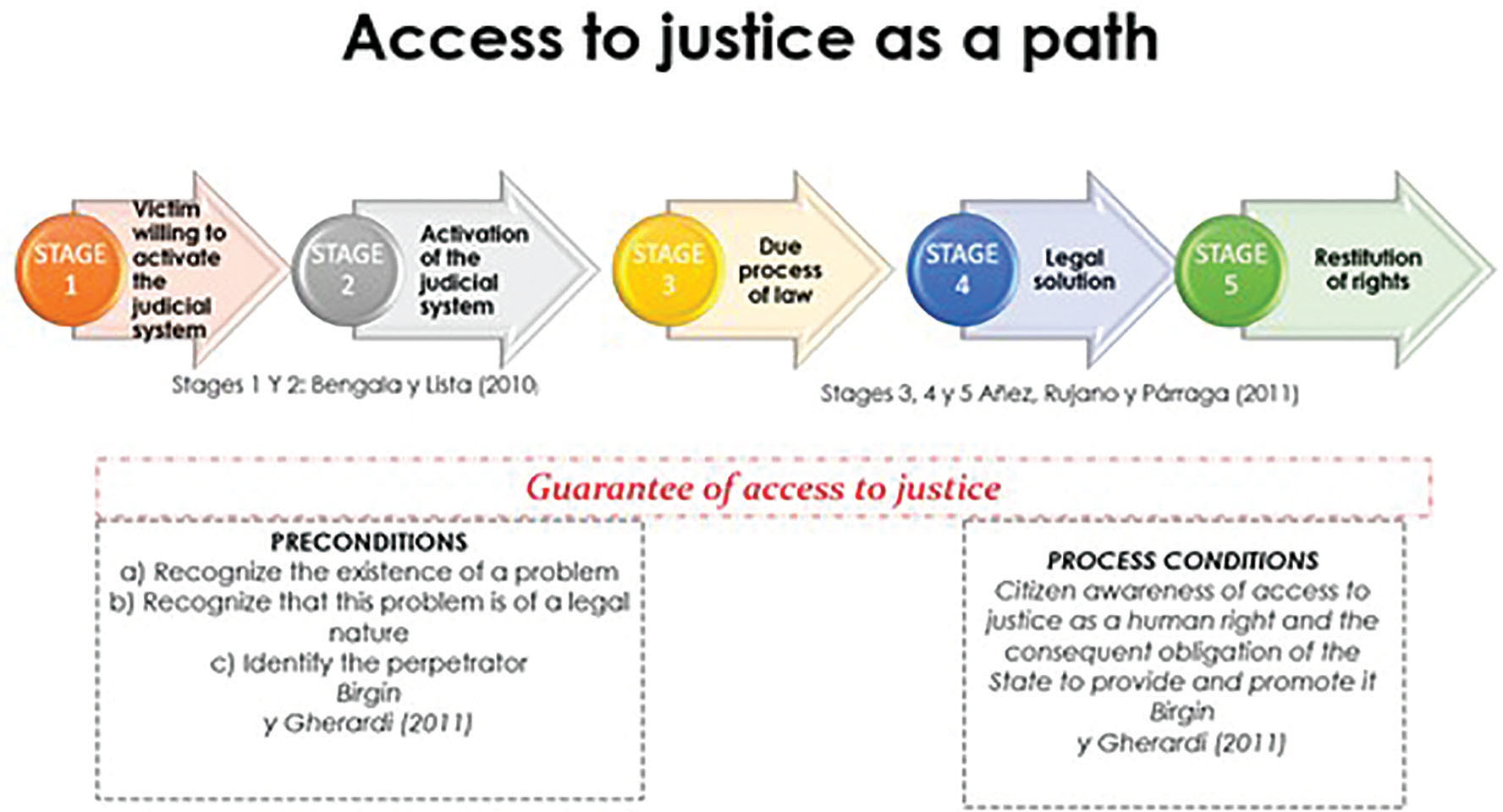

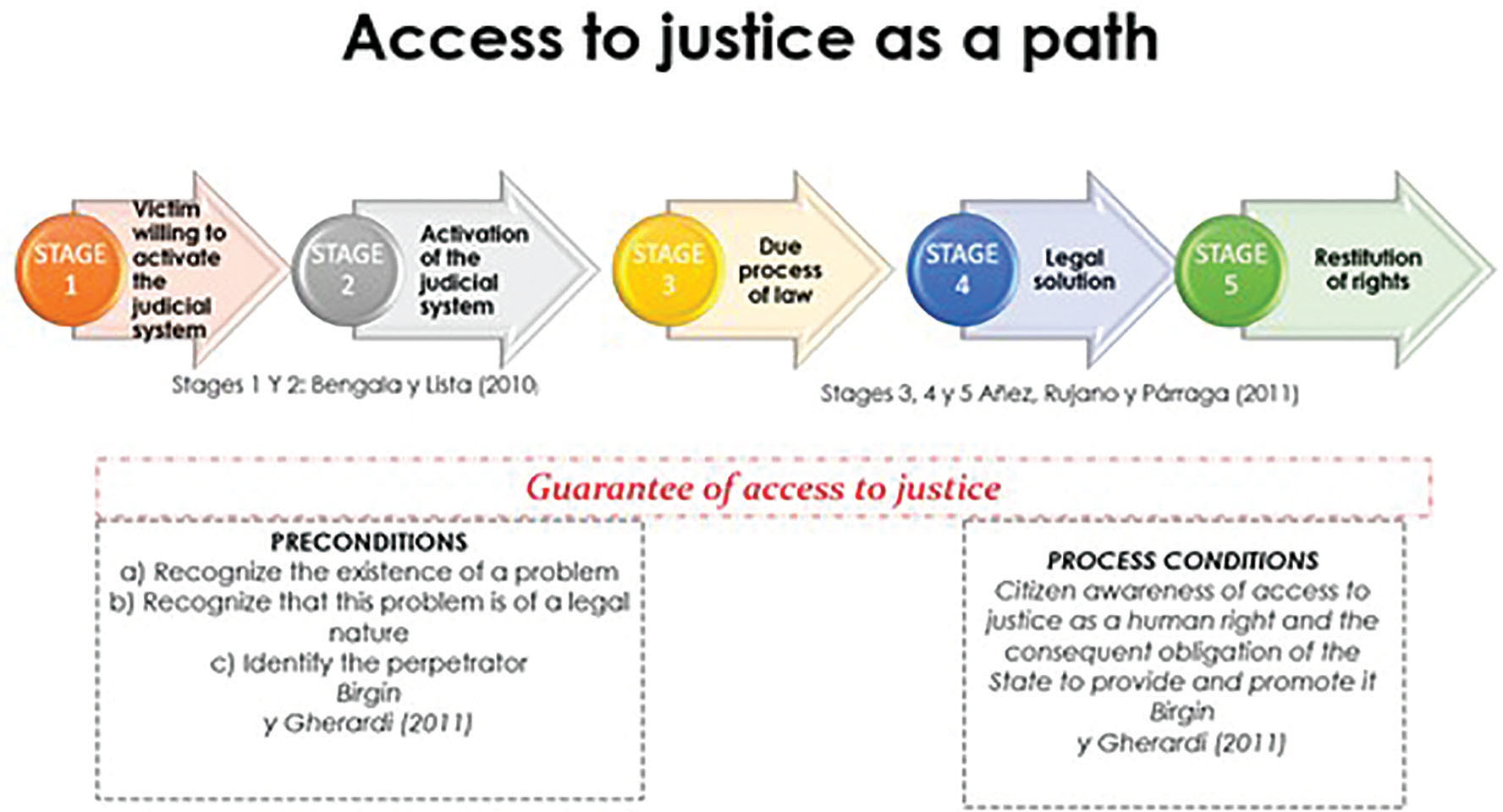

In the penitentiary system of any part of the world there is a paradox regarding the PDL protection of rights since the State is the one in charge of the rehabilitation and care of the inmates; to this extent, there may be rights violation by state agents themselves, which implies that the PDL may possibly have to report to the perpetrator himself. Furthermore, deprivation of liberty by its very nature prevents equal access to justice. It should also be mentioned that the concept of access to justice has constantly evolved. As stated by Bernales (2019), access to justice raises the difficulty of its concept and content determination. For this research, based on the concepts granted by Begala and Lista (2001) and Añez, Rujano and Párraga (2011) it is argued that access to justice is a right consisting of five stages. In the first place, the victim must be willing to report to the judicial system, for which they must have a certain degree of legal literacy and know their rights. Then it must activate the judicial system, the State must guarantee due process of law. This is followed by a legal solution granted by the State and finally its execution and an eventual restitution of rights. This concept summarizes access to justice as a whole journey, addressing all problems and integrality of this right.

As we can see on this graph, access to justice implies a journey that victims have to follow to find justice in order for the State to return their rights. It also implies there are some preconditions such as the predisposition to report, the access to legal representation, knowing how the process is, among others. The guarantee of access to justice is the State’s principal responsibility and where many public and private actors are involved. There are also some process conditions such as the awareness of PDL about human rights and the State obligations. Without these conditions, the reach of the fifth stage is almost impossible.

Graph 1: Path of access to justice

Source: Various authors

Elaboration: The authors, 2019

After outlining the central aspects in relation to contextualization and the theoretical elements, in the following paragraphs the article presents a section about the methodological issues that were followed for information gathering and subsequent study. Then, PDL opinions and experiences about access to justice are analyzed plus the viewpoints of different actors involved around inmates’ access to justice. Finally, a discussion is included in which the results of the study are contrasted with the theory and previous researches in the same line to obtain the conclusions.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research was approached by a qualitative stance guided by previous significant research topics, where questions and hypotheses do not have an exact chronological order since they can be developed before, during or after the collection and analysis of the data (Hernández, 2014). First, these activities often serve to discover what the main research questions are; then, to refine and answer them. Hernández (2014) assures that although there is an initial review of the literature, it can be complemented at any stage of the study supporting from the approach of the problem to the report results. In this type of investigation, it is sometimes necessary to return to previous stages.

2.1 Preparation of the interview

For the present study, in-depth semi-structured interviews were applied to both the PDL and the actors involved in PDL’s access to justice. For the interview guide preparation, an operationalization of variables was made in order to generate and delimit the different axes, categories and codes. With these two interview guides were made: one directed to the PDL in simple terms for their understanding (according to the broad socio demographic profile of the prison population) and some questions were indirectly consulted on susceptible issues to avoid possible re-victimization. The second interview guide was directed to the key actors with the use of more technical terms in which mainly were addressed issues of legal nature.

2.2 Population interviewed

Interviews were carried out during july, august and september of 2020 in Cuenca city. On one hand, 21 interviews were conducted with persons deprived of liberty in the SRC Turi located in Cuenca-Ecuador. This penitentiary center, being regional and one of the largest in the country, receives PDL from different parts of Ecuador. The vast majority of those interviewed were part of the prison population who are in the educational rehabilitation axis. In order to have different points of view, 4 women, 16 men and a transsexual person were interviewed. The 21 interviewed people were in age range between 26-55 years old; about their nationality, there are 18 Ecuadorians and 3 Colombians PDL; about self-perceived ethnic identity, the majority affirmed to be mestizos, also others said mulatto, white and there were an indigenous minority. They had their last domicile before liberty deprivation in various cities of the country such as Cuenca, Cañar, Quito, Ibarra, Machala, Riobamba, Manabí province and in the neighboring country Colombia. The interviewees’ educational level was varied, with people who attended or are currently studying at the Turi SRC Turi from primary level to fourth level education.

This research shows some limitations around the sample of people deprived of liberty who were interviewed because due to the restrictions of the Rehabilitation Center, it was not possible to interview maximum security PDL or PDL that were not linked to the education axis. Furthermore, it is worth highlighting the sincerity with which the majority of the PDL interviewed responded, which allowed the development of various points of view and contrasting them along the proposed lines.

Interviews were also made to actors involved in PDL access to justice. According to Martínez (1991), key informants are “people with special knowledge, status and good information capacity.” Based on this criteria, four private lawyers who practice PDL’s technical defense were sought. In addition, the criteria of Public Defenders specialized in PDLs were asked, plus the opinion from the Penitentiary Guarantees Unit Judge of the city and a former Turi SRC director. In total, 7 key actors involved in the PDL’s access to justice were interviewed. For the selection criterion of private lawyers, the snowball method was used, through which the first interviewees gave clues and names about which actors were suitable to be interviewed. The interviews were applied to both men and women with expertise and knowledge in the matter, thus respecting gender parity criterion.

2.3 Collection and processing of information

In order to obtain and process data, first, a triangulation of the information was carried out. According to Hernández (2014) it is convenient to have several sources of information and methods to collect data, in this way, a greater richness, breadth and depth of data can be achieved. Thus, a better understanding of the phenomenon studied is attained. In qualitative research, data collection and analysis occur practically in parallel. Due to the prohibition of entering electronic devices inside prison, the PDLs interview was carried out only by pencil and paper notes. Thus, the data that were relevant to the investigation were chosen and recorded. To determine the number of PDL’s interviews needed to apply we used the “saturation” criteria. In this way, after a certain number of applied interviews, information obtained was repeated and new information was no longer attained. These data were then digitized and classified according to codes with the Atlas.ti software. In relation to the interviews for the key actors, a recording device was used for its application. After this, recordings were transcribed completely and only key information was classified by codes using Atlas.ti software.

Throughout the collecting process, unstructured data was received, which in the analysis process was provided with structure and meaning. Finally, the research results were generated, then contrasted with theories and explanations given on the matter.

3. RESULTS

The results of the research are presented in two groups: first, from the perception of persons deprived of liberty and then from the experience of the key actors involved in the path of access to justice. In each case the results are broken down into different topics that will be explained in advance.

3.1 Main problems that people deprived of liberty present in the path of access to justice

The following section analyzes the results of the opinions of persons deprived of liberty regarding central and specific issues such as their legal literacy, knowledge to make complaints or to report, knowledge of their prison benefits, possible violations of rights suffered, their predisposition to make a complaint and their opinion on some key institutions in access to justice.

Human rights knowledge

In matters of legal literacy, most people deprived of liberty interviewed state that they have not received education on human rights. The minority of inmates who have received talks on human rights believe that this has been possible because they have accessed privileged places such as radio stations that operate inside jail: “Yes, I have received it, I am on the radio and there are talks there. They (the CRS) only give it to selected people. We have more support from some officials because we work with them on the radio” (EPPL10M) In the opinion of many PDL, the talks have very good results, they consider it a weapon with which they can protect themselves against any right violation. "It would be very good if they would give talks here" (EPPL02M) "There is a lot of ignorance by ourselves" (EPPL01M)

Regarding knowledge about rights that are suspended due to liberty deprivation, the vast majority of PDL interviewed affirm that they do not know about it.

The PDL’s knowledge of filing complaints

In relation to the possibility of the PDL to make complaints and petitions, many interviewees express not knowing how to formulate them; other PDL interviewed affirm they only know: "That the complaint can be formulated to the Judge of Criminal Guarantees." (EPPL01M)

Some PDL feel that knowing how to make complaints is a benefit. “It would be good to know how to write a letter to get to the director, etc. but I don’t know anything." (EPPL10M) Likewise, some PDLs show low expectations regarding their claims: “The truth is, I have sent writings to the judge, coordinator, but there is no answer. I do know how to make complaints, but I have accumulated many complaints that have not been answered.” (EPPLM17DIS)

Knowledge of prison benefits

Regarding the prison benefits, most of the PDL interviewed are aware of them. Many are dissatisfied with the effectiveness and application of prison benefits. Many PDL report delay and difficulty in obtaining a prison benefit. It is expressed: “I have been following my process for six months, but there is no way to contact the authorities (…) there are people who have already paid their sentence, they do not have a lawyer so they do not go out, those of us who have no money stay here” (EPPL13M55) There are cases in which those deprived of liberty have far exceeded the required percentage of punishment to apply for prison benefits; however, they have not been granted such benefits due to process delay.

Violation of rights

Some PDL mention that rights are not guaranteed, another sector believes that only a few rights are guaranteed (mainly health, food and education) (EPPL12M) Regarding health, there are several opinions that agree that it is a right that is quite limited. Few of the persons deprived of liberty interviewed refer to other rights besides health, food and education. The right to freedom of expression is not guaranteed according to some interviewed PDL.

Some PDL interviewed report that in their personal case they have not suffered any violation of rights. Along these lines, a PDL who was born in Colombia states: "I thank God for being here and not in Colombia, there is no overcrowding here, there are many problems in Colombia" (EPPL16M)

On the other hand, some PDL state there have been rights violations against them, however, only 4 PDL assure that they reported this. It is commented: "A violation of rights happened to me, but if it does not become mediatic they do not hear us, right now a guide comes and hits me and nothing happens." (EPPL02M)

Only one PDL belonging to the LGBTI community has denounced on several occasions. Some PDL, despite having suffered some type of violation of rights, have not reported it.

Willingness of the PDL to file a complaint or petition

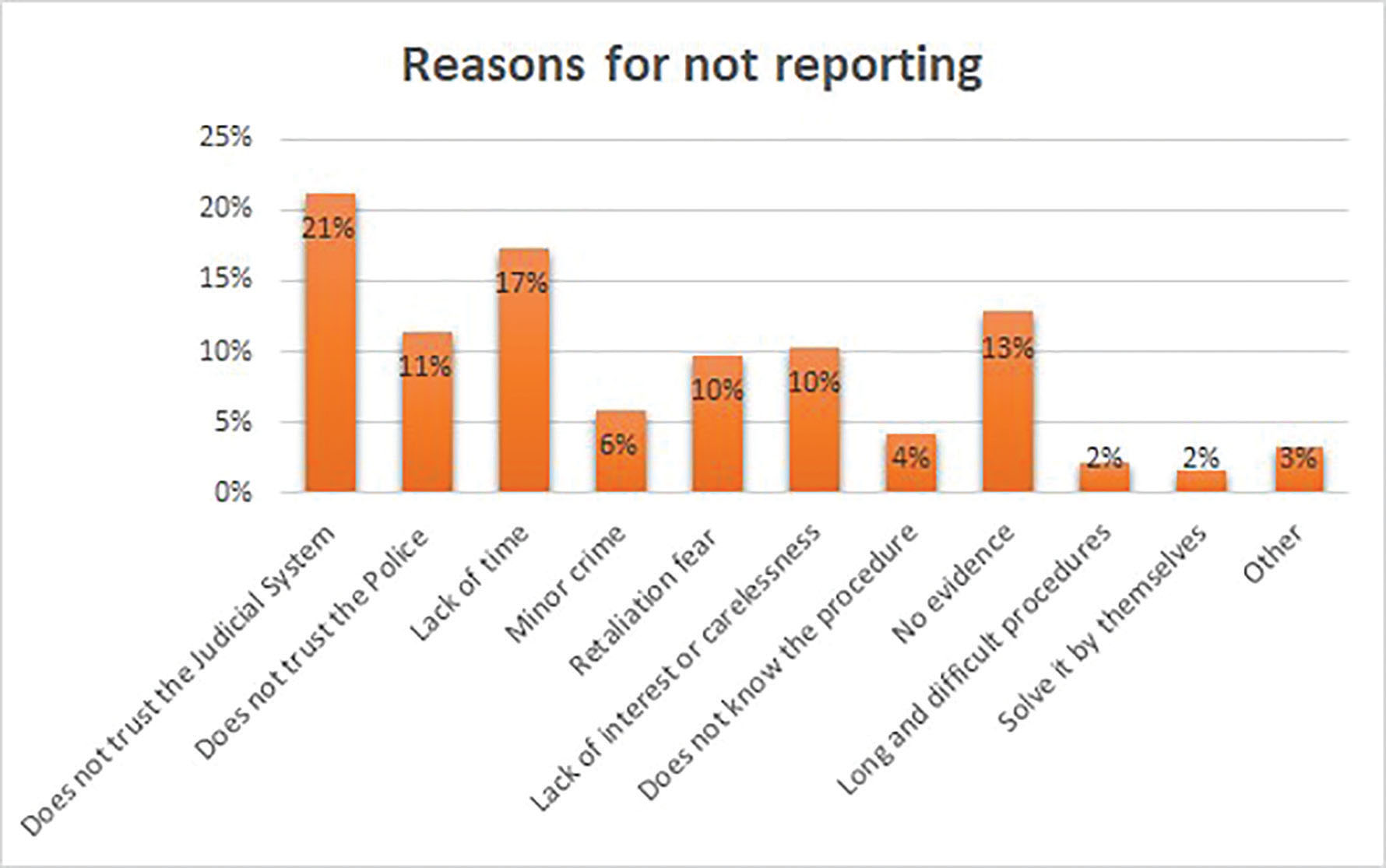

Many interviewees state that they would not file a complaint or report for various reasons that are summarized in the figure 1:

Figure 1: PDL’s reasons to don’t report

Source: Interviews with PDL at SRC Turi (2020)

Elaboration: The authors

As we can see on this table, the major part of PDL don’t report a violation of human rights because of distrust of the judicial system and in second order because they perceive there is a lack of time. The interviews show that some petitions which were given to the administration didn’t have attention or response from them.

On the other hand, very few PDL state that they would report if there were any rights violations.

Regarding the solution the State gave to the PDL’s complaint, the majority of interviewees cannot answer this question because some of them did not suffer a violation of rights, and if they did, they did not denounce it. Indeed, there are only three interviewees who gave an opinion on this point. Everyone agrees that the solution given by the system was not adequate.

PDL’s opinions on some key actors in access to justice

People deprived of liberty are closely linked to certain actors and institutions in order to access to justice. First, they have a day-to-day relationship with SRC Turi officials in order to carry out their rehabilitation. SRC officials are those in charge of ensuring the validity of their rights and reporting any incident. Regarding the perception that PDL have about the work of SRC Turi officials, there are two positions: interviewees who believe officials are doing a good job and other interviewees who think they are not performing their role in a good way.

The opinion that people deprived of liberty have about prison guards is diverse. There are eclectic opinions admitting: “There are some guards who do their job very well, and others don’t, there are two groups. Others delegate their work to us" (EPPL19F) However, there are opposing opinions: "They are prisoners’ puppets, they fulfill what the prisoner gangs say." (EPPL18TRAN)

Another institution that has great importance is the Public Defender’s Office, this dependence provides free legal assistance for people who do not have the resources to hire a lawyer. Many people deprived of liberty state they cannot comment on the service provided by the Public Defender’s Office because they have not had access to it. Interviewees comment: “I have not had access to it. They almost never come” (EPPL19F) Some interviewees affirm the services of a public defender were offered to them; however, they did not need it. Finally, there are PDL that were offered services from a public defender and accepted it. Regarding this last group, there are opinions that negatively rate the service and others that classify it as excellent. It is narrated from the inmates: “I have had a bad experience, we have not had help from public defenders, we have had to look for private lawyers. Although, not all public defenders are this way because there are good public defenders." (EPPL12M) From another minority perspective it is commented: "Excellent, they (public defenders) wanted to help me" (EPPL09MI).

The opinion of PDL on the role their private lawyers have played with respect to their cases is diverse. While some PDL claim that their attorneys have not played a good role, there are other positive opinions. There are interviewees who cannot give their opinion on this topic because they have not had the services of a private lawyer for economic reasons.

Finally, regarding the Judge of Penitentiary Guarantees, some PDL do not know this authority. There are interviewees who consider that the judge does not carry out any work for their processes and does not look at the human side. The PDL interviewed, in their entirety, affirm that in prison there is no justice: "Here there are rules set by the prisoners themselves, and if you do not comply, it can end badly." (EPPL11M)

In table 1 we can see the main problems identified by PDL and key legal informants interviewed at SRC Turi in the path of access to justice. As it shows, PDL didn’t reach the third stage, even less the fifth stage because of problems related with the system, the gangs and their own resources.

Table 1: Main problems found at each stage of access to justice

Access to justice stages |

Problems found |

1. Victim willing to activate the judicial system |

The PDL are unaware of their rights |

The PDL have low expectations of a solution from the state |

|

Fear and intimidation among PDL’s |

|

Fear of retaliation from authorities |

|

2. Activation of the judicial system |

PDL do not know how to report |

Lack of public defenders |

|

Lack of judges of penitentiary guarantees |

|

CRS Turi corruption problems caused by PDL gangs. |

|

3. Due process of law |

Most PDL’s do not reach this stage |

4. Legal solutions |

Most PDL’s do not reach this stage |

5. Restitution of rights |

Most PDL’s do not reach this stage |

Source: Interviews with PDL at SRC Turi and key legal informants in Cuenca (2020)

Elaboration: The authors

3.2 Perception of the key actors linked to access to justice for PDL

This section will analyze opinions given by key actors on the access to justice of the PDL’s regarding topics such as institutional perception, PDL’s rights violations, prison benefits and the main problems of access to justice for the PDL.

Access to justice is a right that requires joint work of several institutions to be guaranteed. In Ecuador, people who work in the rehabilitation system are responsible for carrying out treatment and subsequent society reintegration of inmates, always ensuring PDL’s rights. When any inmate’s rights are violated or when there is a requirement, there is the possibility for making complaints and petitions to authorities. For this, there are the Penitentiary Guarantees Units, which were created in October 2019. The Judge of these units is the one who resolves any complaint around rights violation of persons deprived of liberty. In addition, Judges process penitentiary benefits of freedom and pre-freedom as well as have the duty to make monthly visits to the prisons to verify the respect and validity of rights. In Cuenca, the city where the study is carried out, there are two Penitentiary Guarantees Units. On the other hand, inmates have the right to hire a lawyer of their choice. When a person deprived of liberty cannot hire a private lawyer, the Public Defender services are offered.

The Public Defender’s Office, by constitutional mandate, is the institution in charge of guaranteeing full and equal access to justice for people who, due to their state of defenselessness or economic, social or cultural condition, cannot hire legal defense services for rights protection. In the case of SRC Turi, there is a public defender permanently assigned to it. When illegal conducts classified as crimes are reported, the Office of the Prosecutor intervenes. This is appropriate to highlight, given that a person deprived of liberty may be the victim of rights violations that constitute a crime.

Thus, in this investigation, information has been compiled on the point of view of actors belonging to institutions that have the greatest relevance in access to justice of persons deprived of liberty.

Regarding the perception of the institutions, the interviewees think the administration of the SRC Turi is very good but currently there is a shortage of personnel and delay in the procedures under their responsibility since bureaucratic processes must be carried out. It is stated that many of the officials seek an effective rehabilitation of the inmates, however, mafias are stronger, and officials are threatened by PDL gangs. It is argued that SRC Turi officials are frequently sacked or changed and this causes procedure delays, SRC Turi officials are often elected by political criteria and do not have expertise and experience. It is also stated that workers from SRC Turi administration “(…) do not realize the human system. They only get to fulfill their work, their activity.” (EAP2) It is established that in the SRC Turi a large percentage of PDL do not have disciplinary reports, however, daily problems, riots, violent deaths, entry of prohibited objects, etc. are seen.

In relation to the role played by the Public Defender’s Office, some interviewees believe that it does an excellent job according to its capabilities, since there is only one defender for about 2,700 PDL that are in SRC Turi. On the other hand, there are those who believe public defenders do not promote the processes as they should. It is stated that public defenders, being part of the structure of the State, receive orders not to defend certain legal actions. In addition, it is reported that "they are warning called by the fact of fighting and defending a lot the legal processes of people deprived of liberty" -because it is considered as- "mere formalities" (EFCRS7)

Regarding the Penitentiary Guarantees Unit, the interviewees state that, with the creation of a single Unit in the city of Cuenca, and later the expansion to two units, the access to justice of the PDL was impaired since these matters were judged by 16 judges in the past. In fact, in 2019, in order to guarantee the rights of prison inmates, specialized units were created. Previously, these issues were sent to criminal judges who did not have the expertise to hear these issues. However, the State has placed an insufficient number of judges which has caused a great problem. According to some interviewees, the Penitentiary Guarantees Units have been working respecting rules. It is stated that there is not yet an optimal level of rights protection. A lawyer interviewed indicates that judges are unaware of the internal situation of the prison. In practice, the visit of the Penitentiary Guarantees judge to the SRC Turi is limited by excessive work the judges have and even by security issues. It is assured that the effectiveness of the judge’s visit is due to the fact that inmates are concerned only with personal but not collective requests.

About inter-institutional coordination, interviewees from the Public Defender’s Office and SRC Turi mention there is good coordination. It is reported that communication with the SRC Turi is such that they have even been allowed to work within the center and regarding the coordination with the judicial complex, collaboration has been given so that legal documents can be presented at a special window. For the Penitentiary Guarantees Unit, emphasis is placed on the deficient coordination between the court itself and the SRC Turi, since files for processing penitentiary benefits arrive 99% incomplete, delaying the procedures.

Violations of rights

Regarding violations of rights suffered by the PDL, some private lawyers believe health rights are not guaranteed, since the PDL "have to be dying to be given care" (EAP2). In addition, it is reported that if a PDL file a complaint will be stigmatized.

There are opinions that accuse the mafias as the greatest violators of the rights of the PDL. It is reported that there are occasions when the “caporales” (inmates who command jail areas) do not allow officials and guards to enter “and one meets that person who has already been beaten or who has already been attacked or who has been called to the family to ask for money or things like that and those who do it are the same inmates (...) the same inmates tie them up to other inmates, they even pass electricity on them, they send each other to rape, they send each other to beat and when the official asks what happened nobody says anything because there is fear of retaliations" (EFCRS7)

Prison benefits

The interviewees report that the process for obtaining a penitentiary benefit is very delayed and centralized. Most people deprived of liberty do not access these benefits when they serve 60 and 80% of the sentence, respectively.

In addition, some interviewees are concerned about psychological reports given by the SRC Turi, which is key to accessing a prison benefit, is not carried out with technical and scientific criteria, but prepared based on a single interview.

Main problems of access to justice for PDL

Regarding problems PDL face in accessing justice, the interviewees believe that the lack of sufficient Penitentiary Guarantees Units, as well as public defenders are great challenges PDL face in order to activate the justice system. Likewise, corruption within the SRC Turi is mentioned as a serious problem. It is ensured PDL do not report many situations because they do not know their rights. The lack of legal literacy of vulnerable socioeconomic strata people is accused as an impediment to accessing justice. It is mentioned that access to the Public Defender’s Office is not enough because it is just allowed once a week. Same thing happens with access to private lawyers due to limited schedules. It is mentioned that many times the PDL do not report events for fear of reprisals from the inmates themselves and prison officials. There are opinions that assert that there is an abuse of legal actions by the PDL, based on their classification as a priority attention group, which causes resources and time to be wasted by the SRC. Some problems are described such as the continuous change of officials in the SRC Turi, the lack of interest of the State in giving prison benefits, the lack of trained personnel and overcrowding.

The interviewees report the existence of very vulnerable profiles in people deprived of liberty. It is said that many people who enter prison are generally low-income. Meanwhile, those who do have resources usually do not go to prison because they are given an alternative option to prison. Broadly speaking, it is commented that "60% of those persons deprived of liberty have very limited resources" (EFCRS7)

4. DISCUSSION

Begala and Lista (2001) with a modern vision conceptualize access to justice as a pathway. If we compare the data obtained in the study with that conception, it can be seen that very few interviewees who have suffered rights violations have managed to activate the system, stay in it for the necessary time, and then receive a legal solution. The interviewees report that complaints and requests are not heard. Birgin & Gherardi (2012) establish that some disadvantaged groups face particular difficulties in accessing justice. Grunseit, Forell & McCarron (2008) date that people deprived of their liberty find it very difficult to access justice because, among other causes, the PDL do not trust the system and consider it a waste of time. The results of this investigation agree with this premise since the interviewed PDL consider that, among other things, there is no justice within the prison and they would not denounce a violation of rights because it would be useless. PDL do not trust the system. Some PDL interviewed report on the delay and difficulty in obtaining a prison benefit. It is noted that there are PDL that have already met the time of their sentence and requirements to qualify for pre-release or the semi-open regime, however, their process has stalled and they continue in jail.

Grunseit, Forell & McCarron (2008) found that people deprived of liberty are limited in their right of access to justice, in part due to the so-called “prison culture”. The results agree with what the authors said, since the PDL do not report because they do not want to be considered as whistleblowers, in addition to retrieval from other PDL.

It should be noted that the results indicate that the majority of PDL have not received legal literacy, which is a necessary prior step to access to justice. Despite this, it is interesting to note that the PDL interviewed in the study do recognize themselves as subjects of rights and demand to change situations they consider unfair; at this point the results do not coincide with authors Grunseit, Forell & McCarron (2008) whom affirm that many PDL do not report a violation of rights because they think since they are criminals who have violated the law, they deserve the treatment they receive. Human rights have taken a transcendental role in citizen’s lives in general with the rise of neo constitutionalism and the increasing endowment of rights, to the point that the expression "I have rights" has become more common and robust. It is not surprising that this phenomenon has occurred with more force in a prison population that seeks to unite as a defense mechanism to their situation of liberty deprivation.

On the other hand, it can be seen that common problems in prisons in Ecuador and the region, such as the existence of PDL mafias and corruption, are present at SRC Turi limiting access to justice.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2014), many people who are detained are poor, have low education or are disadvantaged for any other similar reason. The results show there are many people with some other condition of additional vulnerability to deprivation of liberty; many of the interviewees report being from other provinces and countries, being away from their family, having low family income, belonging to minorities such as LGBTI groups, having a low level education, being indigenous, mulatto, etc. The National Comprehensive Care Service (Servicio Nacional de Atención Integral) (2019) corroborates the existence of these vulnerable minorities.

Iturralde (2018) affirms that PDL in Ecuador, before committing criminal acts, lived in an environment of violence and poverty. As established by Coimbra and Briones (2019), Latin American prisons are an instrument of punishment for marginalized minorities and a protected environment for criminals, as we have seen according to the results of this research in relation to the percentage of people deprived of liberty in a situation of extremely high economic vulnerability.

Grunseit, Forell & McCarron (2008) identify a deficit of resources allocated for access to legal information and assistance from PDL. That is adjusted to the results obtained from the investigation. Those who are deprived of liberty state that they do not have adequate access to public defenders, their visits are very sporadic. From different actor’s interviews, a concern is the number of officials who are in charge of access to justice for persons deprived of liberty. It is mentioned a lack of interest from the State towards the treatment and rehabilitation of this group.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This research has revealed, the shortcomings around access to justice for people deprived of liberty in Ecuador have their origin in multiple variables. First, the State organization and the prevailing inequitable social structure that criminalizes poverty; also, failures related to management of penitentiary system are found; and finally, the interpersonal relationships between officials-guides and persons deprived of liberty.

The centrality of the State in relation to the National Social Rehabilitation System implies a bottleneck for processing complaints and the requirements of the PDLs. There is excessive processing and lack of institutional response where the PDL continue to pay their sentence within the SRC Turi when they have already fulfilled the time and requirements to obtain the semi-open regime or pre-release, which would allow them to continue with rehabilitation outside the prison and granting greater operating capacity for the CRS, significantly reducing the levels of overcrowding.

At this point, it is essential to emphasize poverty criminalization, which is evidenced by the fact that the majority of PDL are people in situations of poverty or extreme poverty, which undoubtedly reveals an inequitable social structure where the lack of opportunities, lack of resources and exclusion become the formula to swell the numbers of the SRC. Linked to this, it is worth emphasizing that most of the population interviewed had problems when recognizing their rights, which makes it more difficult for them to recognize a violation and then report it. If PDL do not identify the rights of which they are holders in a correct way, they are not in a position to realize when a violation of rights occurs.

In relation to the failures related to management of penitentiary system, it is visible that within the SRC there is no adequate guarantee of rights, free legal advice is limited and difficult to access, social reintegration programs, especially legal literacy, are not reaching all PDL due to lack of officials at SRC Turi and related institutions and agencies such as the Penitentiary Guarantees Unit and the Public Defender’s Office.

The interpersonal relationships between officials-guides and persons deprived of liberty show that within the SRC there is a parallel justice exercised by mafias and groups that govern the SRC marked by extortion and impunity, where the PDL who have suffered some type of violation cannot access their legitimate right for fear of reprisals. These problems, together with cases of corruption within the SRC, prevent the facts from being brought to the attention of the respective authorities.

Regarding the personal experiences of persons deprived of their liberty in access to justice, it can be concluded that the majority have not received legal literacy, in addition, PDL find few problems in accessing justice that are summarized in the following categories:

The PDL think that their problems and complaints will not be solved or listened to

Out of fear or fear of other inmates

For fear of reprisals from the authorities

Because it is a delayed process and they need money to carry it out successfully.

For not knowing how to report or send a petition.

In addition, the study suggests that the inequity of access to justice is caused because of inefficiencies and structural problems in the country’s judicial system. Given that access to justice generally depends on relatives or friends of those deprived of liberty who manage their judicial processes, the prisoner has limited or no management capacity due to the context of confinement; therefore, those prisoners whose family members have better management will be more likely to access justice than those who lack this support. Unfortunately, most of PDL that were interviewed had their last place of residence at other provinces far away from “Turi” PDL are often far away from their home, family and friends.

This panorama in relation to access to justice for PDL puts on the table some points of analysis to identify why there is such a deep crisis at the level of the Ecuadorian penitentiary system. It also shows the importance of gradually deconstructing the paradigm of social rehabilitation, its functioning, the budget allocation given, the forms of relationship within the SRC and the demand of the PDL for a dignified treatment that has been expressed for decades and due to the structural failures of the State’s attention, it becomes more and more violent and unmanageable.

Finally, it is important to highlight the importance of researching the different problems of the PDL by listening to their opinions, in order to understand the internal dynamics of this population and seek structural solutions to the prison regime. It is suggested for future studies to contrast different realities from other Rehabilitation Centers both in Ecuador and in other latitudes that are part of the region to determine provisions and guidelines from international organizations that allow strengthening human rights and access to justice for this population.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aguilar, G. (2017). La dignidad de las personas privadas de libertad dentro de los centros de rehabilitación social en el Ecuador. Estudio de caso. Available at: https://repositorio.uisek.edu.ec/handle/123456789/2340

Añez, A., Rujano, R., & Párraga, J. (2011). Seguridad ciudadana y Acceso a la justicia. Revista de Ciencias Jurídicas de la Universidad Rafael Urdaneta, 11–29.

Arrias Añez, J. C. D. J., Plaza Benavides, B. R., & Herráez Quezada, R. G. (2020). Interpretación del sistema carcelario ecuatoriano. Universidad Y Sociedad, 12(4), 16-20. Available at: https://rus.ucf.edu.cu/index.php/rus/article/view/1607.

Asociación Interamericana de Defensorías Públicas. (2014). Guía Regional para la defensa pública oficial y la protección integral de las personas privadas de la libertad. Available at: https://www.defensoria.gob.ec/images/defensoria/pdfs/lotaip2014/info-legal/Guia_defensa_publica_proteccion_personas_privadas_libertad.pdf

Begala, C. Lista, S. (2001) Pobreza, marginalidad jurídica y acceso a la justicia: condicionamientos objetivos y subjetivos. CIJS, Centro de Investigaciones Jurídicas y Sociales. Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Sociales. UNC. Anuario (no. 5 1999-2000). 405–430.

Bernales, G. (2019). El acceso a la justicia en el sistema interamericano de protección de los derechos humanos. Revista Ius et Praxis, Año 25, Nº 3, 277–306. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-00122019000300277

Birgin, H., & Gherardi, N. (2012). La garantía de acceso a la justicia: aportes empíricos y conceptuales. México DF: Fontamara.

Código Orgánico Integral Penal. (2014). Quito, Ecuador: Official Register Supplement 180.

Coimbra, L. O., & Briones, Álvaro. (2019). Crimen y castigo. Una reflexión desde América Latina. URVIO. Revista Latinoamericana De Estudios De Seguridad, (24), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.17141/urvio.24.2019.3779

Cuesta, C., 2015. Análisis de las fallas de implementación de la política pública de seguridad ciudadana en el Ecuador (2007-2015). Thesis (Master). Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Sede Ecuador.

El Comercio Newspaper. (2021) La matanza de 79 presos en Ecuador está entre las 10 más violentas de Sudamérica. Available at: https://www.elcomercio.com/actualidad/seguridad/matanza-presos-ecuador-violentas-sudamerica.html

González, J. (2018). Los derechos humanos de las personas privadas de la libertad. Una reflexión doctrinaria y normativa en contraste con la realidad penitenciaria del Ecuador. Revista Latino Americana de Derechos Humanos, 189–207.

Grunseit, A. & Forrel, S. & McCarron E. & Law and Justice Foundation of New South Wales (2008). Taking justice into custody: the legal needs of prisoners. Sydney: Law and Justice Foundation of New South Wales.

Hernández, R. (2014) Metodología de la Investigación. Sixth Edition. México D.F: McGraw-Hill / Interamericana Editores, S.A. DE C.V.

Intriago Muñoz, G., & Arrias Añez, J. (2020). Hacinamiento de los centros penitenciarios del Ecuador y su incidencia en la transgresión de los derechos humanos de los reclusos. RECIMUNDO, 4(1(Esp)), 13–23. Available at: doi:10.26820/recimundo/4.(1).esp.marzo.2020.13-23

Iturralde, C. A. (2018). La educación superior en las cárceles. Los primeros pasos de Ecuador. Alteridad, 13(1), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.17163/alt.v13n1.2018.06.

Martínez, M. (1991). La investigación cualitativa etnográfica en educación: Manual teórico – práctico. Venezuela: Texto.

Núñez, J. 2006. Ciudad Segura I, Magazine. Citizen Studies Program. Flacso, Ecuador.

Oña, D. (2021) “El de las cárceles es un problema que se ha venido deteriorando por años” Magazine GK City. Portada.

Pazmiño, E. (2011). Derechos Humanos y Acceso a la Justicia Personas y Grupos de Atención Prioritaria. Quito: V Y M Gráficas.

Permanent Committee for the Defense of Human Rights (2019). Resumen del informe sobre la crisis carcelaria en el Ecuador. Available at: https://www.cdh.org.ec/informes/398-resumen-del-informe-del-cdh-sobre-crisis-carcelaria-en-ecuador.html.

Servicio Nacional de Atención Integral a personas adultas privadas de la libertad y a adolescentes infractores (2019) Transformación del Sistema Nacional de Rehabilitación Social. Available at: https://www.atencionintegral.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/PROYECTO-TRANSFORMACI%C3%93N-SISTEMA-REHABILITACI%C3%93N-SOCIAL_VF_15NOV2019.pdf

Sistema Nacional de Rehabilitación Social (National Social Rehabilitation System), 2020. Reglamento del Sistema Nacional de Rehabilitación Social. Available at: https://www.atencionintegral.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Reglamento-del-SIstema-de-Rehabilitacio%CC%81n-Social-SNAI-2020_compressed.pdf (información revisada en 09-06-2021)

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2014). Early access to legal aid in criminal justice processes: a handbook for policymakers and practitioners. New York: English, Publishing and Library Section, United Nations Office at Vienna.

Vera, Mónica, 2019. Crisis del Sistema Penitenciario en el Ecuador: más allá de una declaración de estado de excepción. INREDH Foundation.

Received: July 1st 2021

Accepted: September 22rd 2021

_______________________

* Researcher of the Research Group on Population and Sustainable Local Development (PYDLOS) - Interdisciplinary Department of Space and Population (DIEP), University of Cuenca, Ecuador. andres.ramirez@ucuenca.edu.ec

** Coordinator of the Research Line on Citizen Security and Human Rights of the Research Group on Population and Sustainable Local Development (PYDLOS) - Interdisciplinary Department of Space and Population (DIEP), University of Cuenca, Ecuador. antonia.machado@ucuenca.edu.ec