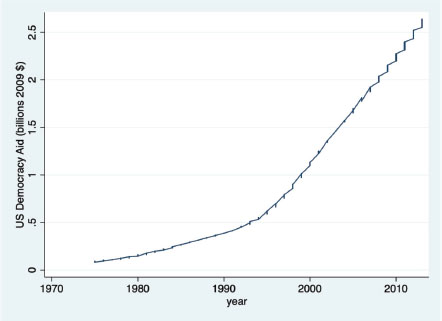

Figure 1: US Democracy Aid, 1975-2013

COSTLY SIGNALS? DEMOCRACY AID SHOCKS AND POLITICAL REPRESSION, 1981-2013

ALLEGRA E. HERNANDEZ1; JAMES M. SCOTT2

Abstract Developed states increasingly turned to democracy assistance strategies as the Cold War came to an end. A number of recent studies conclude that such aid positively affected democratization in recipients. But, like foreign aid, democracy assistance allocations are subject to change, sometimes dramatically. In foreign aid, sudden, sizable reductions – or aid shocks (e.g., Nielsen et al. 2011) – can have severe consequences, precipitating conflict in the recipient state. How do democracy aid shocks affect recipient states? This analysis examines the effects of sudden withdrawals of democracy aid – or democracy aid shocks – by the U.S. on recipient regime behavior, specifically, their treatment of citizens and civil society groups. We argue that democracy aid shocks trigger repressive action by recipients resulting in harmful human rights practices by the regime. Examining U.S. democracy aid to the developing world from 1982-2013, we find that, after controlling for other relevant factors likely to affect the human rights practices of a regime, democracy aid shocks are associated with subsequent repression of human rights in the recipient state. Our analysis thus sheds light on an external factor affecting human rights practices within states, as well as an important element of the consequences of democracy aid decisions. We conclude by assessing the implications for democracy promotion strategies and human rights behavior.

Keywords: democracy aid, aid shocks, human rights, democratization

Summary: 1. COSTLY SIGNALS?. DEMOCRACY AID SHOCKS AND POLITICAL REPRESSION, 1981-2013. 2. DEMOCRACY AID IN CONTEXT. 3. DEMOCRACY AID SHOCKS AND HUMAN RIGHTS. 4. DATA AND METHODS. 5. RESULTS. 6. CONCLUSION.

COSTLY SIGNALS?

DEMOCRACY AID SHOCKS AND POLITICAL REPRESSION, 1981-2013

Aid from developed states to support and promote democracy in other countries grew into an increasingly significant component of foreign aid strategy as the Cold War came to an end and the post-Cold War world began. Numerous recent studies conclude that such aid positively affected democratization and human rights behavior in recipients (e.g., Dietrich and Wright 2015; Finkel et al. 2007; Heinrich and Loftis 2017; Kalyvitis and Vlachaki 2010; Scott 2012; Scott and Steele 2011). But, like foreign aid, democracy assistance allocations are subject to change, sometimes dramatically, as donors reconsider their priorities, the possibilities and progress in a potential recipient, and conditionalities they wish to impose. In the foreign aid field, sudden, sizable reductions – or aid shocks (e.g., Nielsen et al. 2011) – can have severe consequences, precipitating conflict in the recipient state. Should we anticipate a similar result for democracy assistance in areas related to democracy and human rights? How do democracy aid shocks affect recipient states?

We examine the effects of a sudden reduction of democracy aid – or a democracy aid shock – on recipient regimes, specifically, on their treatment of citizens. Focusing on abrupt reductions of democracy aid to civil society groups, we examine U.S. democracy assistance to the developing world from 1981-2013. While this analysis focuses on the effects of shocks to U.S. assistance, it is applicable more generally to the consequences of democracy aid shocks from other donors as well. We argue that these democracy aid shocks are likely to trigger repressive action by recipient state regimes by weakening civil society actors vis-à-vis the regime and by simultaneously signaling regimes that human rights and democracy are no longer important to donors. This combination, we argue, incentivizes regimes to engage in harmful human rights practices. Our empirical tests of the human rights effects of democracy aid shocks provide support for our theorized relationship, controlling for other relevant factors likely to affect the human rights practices of the regime. Our findings thus shed light on a significant external factor affecting human rights practices within states, as well as an important consequence of democracy aid decisions. In particular, our evidence indicates that democracy aid shocks have significant, negative, and perhaps unintended consequences in the lives and well-being of many people and are likely to necessitate subsequent difficult policy decisions to address their impact.

DEMOCRACY AID IN CONTEXT

Although foreign aid is frequently utilized as a tool by states to accomplish foreign policy goals, prior to the end of the Cold War, US foreign aid was rarely used to promote or support the democratization of states. Rather, the US used foreign aid to deter the spread of communism and the influence of the Soviet Union (Scott and Carter 2019). However, as the Cold War wound down, the U.S. and other donor states increasingly developed foreign aid strategies to promote democracy globally (e.g., Bridoux and Kurki 2014; Meernik et al. 1998; Mitchell 2016; Scott and Carter 2019).

According to AidData (Tierney et al. 2011), democracy aid from developed states grew from negligible amounts ranging from 0-2% before the end of the Cold War to 10-15% of foreign aid by the 2000s. For the US, democracy assistance grew from less than 2% of aid to about 14% from 1975-2010 (Scott and Carter 2019). Most US democracy aid is administered by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), which provides targeted, relatively small aid packages to promote and support democracy and build capacity in individuals, groups, and institutions in the recipient state. US democracy aid goes to civil society organizations (about one-third of US democracy aid) and to political parties and political institutions (about two-thirds of US democracy aid).

Studies of foreign aid and democracy aid generally examine the determinants of their allocation or their effects on such things as economic growth, human rights, and/or democracy. In terms of allocations, studies of both foreign aid and democracy aid conclude that complex calculations involving donor interests and relationships, recipient needs, humanitarian and ideational purposes, feasibility concerns, bargaining with recipients, media attention, and others drive aid decisions (e.g., Alesina and Dollar 2000; Apodaca and Stohl 1999; Balla and Reinhardt 2008; Boutton and Carter 2014; Dietrich 2016; Drury et al. 2005; Heinrich 2013; Heinrich et al. 2018; McKinlay and Little 1977; Nielsen 2013; Nielsen and Nielson 2010; Peterson and Scott 2018; Scott and Carter 2019; Scott et al. 2020).

Studies of foreign aid outcomes examine its effects on development, human rights, democracy, conflict, and a variety of other matters (see, for example, Apodaca 2017; Dasandi and Erez 2017; Findley 2018; Girod 2018; Yiew and Lau 2018). With respect to democracy in particular, most analyses conclude that general foreign aid does not promote democracy (e.g., Knack 2004), but more targeted and focused democracy aid is another matter. Recent research concludes that democracy aid is likely to promote democratization in recipient states (e.g., Askarov and Doucouliagos 2013; Dietrich and Wright 2015; Finkel et al. 2007; Heinrich and Loftis 2017; Kalyvitis and Vlachaki 2010; Scott and Steele 2011).

Foreign aid and democracy aid also have distinct and different relationships to human rights. Some studies argue that recipient human rights performance affects foreign aid allocation, especially at the selection or “gatekeeping” stage (e.g., (e.g., Apodaca and Stohl 1999; Blanton 2005; Cingranelli and Pasquarello 1985; Meernik et al. 1998). Foreign aid’s effect on human rights is less clear. For example, Dasandi and Erez (2019) argue that foreign aid contributes to both economic growth and human rights repression, while Neumayer (2003) and Regan (1995) find little connection.

The link between democracy aid and human rights is somewhat clearer, however. A recognized benefit of democracy is its association with better human rights performance (Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2005; Davenport 2007; Poe and Tate 1994). By positively contributing to democratization, democracy aid generally tends to contribute to the maintenance of or improvement in the recipient regime’s positive human rights practices (e.g., Scott 2012). This is especially true when considering that US democracy aid is most often directed to regimes that are most likely to democratize and, indeed, display initial movement or openings toward democracy that attract the aid in the first place (e.g., Nielsen and Nielson 2010; Peterson and Scott 2018; Reinsberg 2015; Scott and Carter 2019; Scott et al. 2020). Targeted US democracy aid is allocated to promote and support democratization, which includes and involves improved human rights records by the recipient regime. Some studies indicate a similar, positive effect from democracy aid on human rights as well (e.g., Scott 2012). Given the positive link between democracy and human rights performance, what happens when democracy aid is abruptly reduced?

DEMOCRACY AID SHOCKS AND HUMAN RIGHTS

We extend existing scholarship on general foreign aid shocks, which focuses on consequences for civil war, to democracy assistance and its consequences for human rights. We argue that abrupt and substantial reductions of democracy assistance – democracy aid shocks – are likely to prompt repression and deteriorating human rights practices in recipient regimes. Several strands of previous work contribute to this argument, beginning with the underlying foundations for when donors provide – and reduce – democracy aid.

We ground our argument in the general foundations of the determinants of democracy aid allocations, which helps to explain the imposition of democracy aid shocks in the first place. As previously indicated, numerous studies of foreign and democracy assistance have concluded that aid allocations rest on calculations of donor interests, recipient needs, humanitarian and ideational purposes, feasibility, and other concerns. These determinants also provide foundations for understanding decisions to suspend, reduce, or eliminate aid as well. In the context of our study, four reasons for democracy aid shocks are particularly important and set the foundations of our argument about the effects of these decisions.

First, a “graduation” effect structures democracy aid allocation decisions. In general foreign aid, donors may reduce or end assistance when a recipient achieves the purpose of the aid (e.g., South Korea no longer receives development assistance). With respect to democracy aid, recipient countries consolidating successful democracies generally find democracy aid dramatically reduced or eliminated as “unnecessary,” potentially replaced by other forms of support and assistance. For example, Scott et al. (2019; 2020) find that US democracy assistance is dramatically reduced as recipients progress to consolidated democracies. We would not expect such “shocks” to result in worsening human rights in response, so this “graduation” condition helps to set a boundary condition for the effect of democracy aid shocks on recipient human rights performance.

Second, the aid conditionality literature indicates that democracy aid shocks may result from donor efforts to punish or incentive recipients (e.g., Crawford 1997; Montinola 2010; Temple 2010). As scholars of foreign aid have argued, the effectiveness of foreign aid is partly based on how incentivized recipient regimes are to meet the conditions outlined by the donor state (Girod and Tobin 2016). The literature describes two types of aid conditionality – establishing particular policy requirements in return for access to foreign aid, or adjusting the flow of aid (e.g., granting, withholding, delaying, etc.) based on preferred conditions recipient states must meet. Donor states may require regimes to follow certain guidelines or meet outlined standards (Girod 2018), or they may demand that recipient regimes change the structures of their government, economy, and/or policies in order to create sufficient institutional capability to achieve donor goals for the aid, which is known as structural adjustment agreements. When recipient states do not comply with conditions, the donor state is then forced with the decision to cut off aid. In terms of democracy aid then, aid shocks may be spurred by donor attempts to withhold assistance in order to incentivize better progress toward democratization and improvement in human rights, or to punish the declines in either or both.

In general, most studies conclude that conditionality does not typically work (Crawford 1997; Girod 2018; Montinola 2010; Temple 2010). Prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, donor states may have outlined aid conditions, but they were frequently ignored (Bermeo 2016; Dunning 2004). Moreover, donor states often lack incentive to withdraw aid as the donor focuses on broader geopolitical goals such as alliances, rivalries, economic relationships, and others (e.g., Bearce and Tirone 2010; Morgenthau 1962; Nielsen 2013). This highlights an important point of aid literature: threats to withdraw aid are generally only carried out when the donor state has little or no strategic reason to provide the aid in the first place (Bearce and Tirone 2010; Bermeo 2016; Dunning 2004). In effect, withdrawal of aid is rarely about conditions met; rather, it is about whether or not strategic interests warrant providing/continuing the aid. Other research indicates that recipient states are also more likely to comply with prearranged aid conditions when recipients are more democratic (Montinola 2010) and when institutional capability is at a higher level, or, in other words, when the recipient state has the capacity to do what is asked of it (Noorbakhsh and Paloni 2007).3

In the arena of human rights and democracy, for example, granting, withholding, delaying, or reducing general foreign aid is not often related to human rights improvements and, at times, just the opposite (e.g., Burnside and Dollar 2000; Alesina and Dollar 2000; Nielsen 2013; Schraeder, Hook and Taylor 1998). According to Dasandi and Erez (2017), broad foreign aid may contribute to economic development, but often may result in human rights violations by the recipient regime as well. Similarly, Regan (1995) found no effect for assistance on recipient human rights records across the Carter and Reagan administrations.

The disconnect between aid conditionality and human rights improvements establishes that donors can produce unexpected, even contrary, consequences with foreign aid decisions. Offers of assistance may or may not prompt desired behavior, while suspension or reduction of aid rarely produces changed behavior, especially, it seems, when it comes to human rights performance. Accordingly, we draw on this general finding to build our expectation that democracy aid shocks are likely to result in counter-productive outcomes when it comes to human rights.

Third, democracy aid donors are driven in part by priorities of interest and opportunity to shift funds from some recipients to others as well. For example, according one recent analysis of the shifting targets of US democracy aid, “Latin America and Eastern Europe received greater priority in the early post-Cold War years, while the Middle East and South Asia (i.e., Iraq and Afghanistan) received greater attention in the post-9/11 years” (Scott and Carter 2016, 309). Similarly, within regions, interests and opportunities also drive shifts in targets for aid. In Latin America, US democracy aid targeted El Salvador and Panama before 1990, and Haiti, Colombia, and Mexico after the end of the Cold War (Scott and Carter 2016). In the Middle East, Egypt and Jordan dominated US democracy aid prior to 2001, while (not surprisingly) Iraq was the central target after that (Scott and Carter 2015). Hence, donor attention and interests may lead to re-prioritization of aid allocations, but such reprogramming may well trigger unintended negative consequences in previous recipients as aid resources abruptly decline.

Finally, previous studies also suggest that calculations focusing on lack of feasibility and danger also contribute to decisions to avoid, suspend, reduce, or eliminate aid as well. Previous foreign aid studies indicate that poor or deteriorating human rights conditions within the recipient state may reduce assistance (e.g., Cingranelli and Pasquerello 1985; Poe 1992). Moreover, dramatic changes in regime conditions suggest instability and danger to the donor state, which combine to reduce aid (e.g., Peterson and Scott 2018; Scott et al. 2020). Conversely, in democracy aid allocations, research indicates that donors target aid to countries showing some progress toward democracy, as well as relative stability, because those recipients demonstrate feasibility for continued improvement, to which aid might contribute (e.g., Nielson and Nielsen 2010; Scott and Carter 2019; Scott et al. 2020). This literature suggests that changes in regime characteristics and human rights performance are linked to democracy aid allocation decisions as well.

Building from these foundations, we draw on and extend a cluster of recent studies of conflict and foreign aid shocks to develop and apply our argument to democracy aid, an as-yet unexamined phenomenon. Previous studies of general foreign aid shocks –or “deviations from expected aid flows” (Gutting and Steinward 2015) – establish the foundations of our argument. This literature demonstrates that foreign aid shocks generally result in increased conflict on both a large and small scale in recipient states (e.g., Nielson et al. 2011; Savun and Tirone 2012). We draw on this argument, refocus it, and apply it to democracy aid. We thus argue that, when recipient regimes experience democracy aid shocks, they are more likely to engage in subsequent repressive behavior towards civil society groups and their citizens.

As Nielsen et al. (2011, 221) argue, foreign aid shocks affect the strategic calculations of both rebel groups and the recipient governments: “rapid changes in aid flows—aid shocks—can grow large enough to materially affect the balance of power between a government—the sovereign recipient of aid flows—and potential rebels.” The sudden withdrawal of aid threatens the established status quo. The government may no longer be able to maintain its payoffs to rebels, and the aid shocks may force the regime to “provide fewer services or side-payments” and “spend less of the diverted aid on the military” (Nielson et al. 2011, 222). The logic continues that due to the weak position of the government, rebel groups are incentivized to demand more in order to keep peace. This may lead to a new bargaining range favoring potential rebels but is subject to a significant commitment problem. As Nielson et al. (2011, 222) put it

Because deep aid cuts may shift the balance of power radically, rebels are likely to demand more resources than the government can provide in the short term. Thus, a promise of increased side-payments from the government to rebels often requires pledges drawing on future resources. But promises of future transfers are contingent on the newly realized balance of power, which favors the rebels. If aid flows resume, the government’s newfound strength will likely embolden it to renege on its commitment, making its current promises of future transfers noncredible (Powell 2006, 236). Because the expected rebel payoff from conflict is probably greater than any offer the government can credibly announce, we argue that aid shocks heighten the probability of armed conflict. Therefore, any settlement the government reaches is not credible, and the rebel group is likely to gain a greater payoff by choosing conflict.

We refocus and apply this argument to democracy aid shocks and human rights behavior. In a democracy aid shock, the sudden reduction of democracy assistance affects the bargaining balance between a regime and those seeking democratization. In effect, the logic/incentives of general foreign aid shocks are effectively reversed: democratizers in the public – especially civil society organizations and opposition parties – are placed in a weaker, more vulnerable position because of the sudden and substantial reduction of support. The regime is then incentivized to demand more or, more specifically, to engage in more repressive behavior, in order to achieve its goal (the preservation of its power and control). While democracy aid does not provide resources to democratizers to offer side-payments to the government in return for more openness or democracy (unlike the resources provided by foreign aid to regimes to potential rebel groups in the foreign aid shock literature), its contribution to the capacity of democratizers and its signal of support from external democracy sponsors shape regime calculations nonetheless.

This logic, we argue, is especially the case with severe and sudden reductions of democracy aid to civil society actors. Civil society democracy aid is particularly important, as that type of democracy assistance expressly empowers societal groups (e.g., Dietrich 2013; Dietrich and Wright 2015; Scott and Carter 2019). Such groups advocate for changes (democratization, support for human rights and participation) in the regime and political system. As Dietrich (2013) concludes, concerns over the quality and intentions of governance often lead donors such as the US to bypass the recipient state government and provide aid to and through non-state actors, including civil society groups. Moreover, as Dietrich and Wright (2015) argue, civil society aid strengthens societal and opposition groups and contributes to democratization, albeit somewhat indirectly. Other evidence suggests meaningful benefits for such groups when it comes to their capacity to mobilize the public and affect change (e.g., Finkel 2003; Gazibo 2013; Gyimah-Boadi et al. 2000; Gyimah-Boadi and Oquah 2000; Gyima-Boadi and Yakah 2013; Hearn 2000; Robinson and Friedman 2007). Indeed, as Savun and Tirone (2011) conclude, democracy assistance improves the capacity for civil society to monitor state actions and can act as a brake on violent intentions and actions of the state (see also Braithwaite and Licht 2020).

It is in part for this reason that governments compete with civil society organizations over foreign aid funds in general and often try to limit how much aid reaches civil society groups (e.g., Dupuy et al. 2016). Dupuy et al. (2016) demonstrate that civil society organizations and governments are often forced to compete over aid awards, with governments going so far as to attempt to limit the amount of aid reaching these organizations. Moreover, the reach that civil society organizations possess has led many governments to increase restrictions on them (Dupuy et al. 2016). This makes aid targeted towards civil society organizations all the more important given the demonstrated efforts of many regimes to limit the check that well-funded civil society organizations place on them. While democracy aid remains relatively small when compared to other types of aid, the aid is sizeable enough to cause ramifications and change how governments behave.

When a democracy aid shock involving a sudden reduction of support to civil society organizations occurs, those actors, and their capacity to demand democratization, are weakened vis-à-vis the regime. Civil society democracy aid shocks create vulnerabilities for the civil society groups. They weaken societal actors challenging the regime, diminishing their capacity to mobilize the public, monitor state actions, and influence the practices of the regime. Such shocks also send dangerous signals to the regime. The cue from the democracy aid donor(s) provided by the shock reduces regime incentives to liberalize and contribute to opportunities and incentives to try to preserve or consolidate its hold on power. Regimes are thus less likely to maintain progress toward democracy and more likely to undertake efforts to crack down on civil society groups in order to sustain or gain power. These calculations thus reduce regime caution and lead to an increase in repression and violence in order to achieve the goal of preserving power and, perhaps, reversing liberalization/democratization.

As a consequence, civil society aid shocks are especially likely to prompt repressive behavior by the regime in order to improve its control and slow or reverse democratization. As an example, the case of Guatemala is instructive. Following previous incidents of democracy aid shocks, the US dramatically reduced civil society democracy aid to Guatemala in 2006. Incidents of repression and violence subsequently increased, with civil society organizations less able to mobilize, speak out against the government, and draw on support from the U.S. as a sponsor. Even when President Colom took office two years later, the weakening effects of the civil society democracy aid shock continued to contribute to civil society and contribute to incidents of repression and violence.

While civil society organizations are obviously not the only factor relevant to human rights performance, their capacity is important to shaping regime performance. However, when civil society experiences a democracy aid shock, their capacity diminishes, and the regime is less constrained in its behavior. Hence, we argue that democracy aid shocks lead to increased political violence in the form of state repression. We therefore expect to see an increase in human rights repression by the recipient regime toward its citizens following democratic aid shocks. This leads to our central hypothesis:

Hypothesis: Recipient states facing civil society aid shocks are likely to engage in repressive behavior towards citizens.

DATA AND METHODS

We examine country-year US democracy aid from USAID to the developing world from 1981-2013 (see Djankov et al. 2009 on donor selection). This time-series-cross sectional (TSCS) data enables both comparisons between countries experiencing shocks and those who do not (cross-sectional), and within-country comparison of the impact of shocks on a country’s human rights performance both pre- and post-shock (time series). We filter consolidated democracies from the data to avoid including “shocks” caused by the reduction or elimination of democracy aid to countries that have “graduated” from the need for such assistance.4

Our dependent variable is human rights, which we measure in two ways for robustness. First, we use the Political Terror Scale (Gibney et al. 2013), a 1-5 ranking of human rights performance focusing on imprisonment, torture, and extrajudicial killing in which 5 represents the worst conditions. For ease of interpretation (consistency with the Physical Integrity Index), we invert this scale for our models, so that higher scores represent better human rights performance. Second, we also measure a country’s human rights performance with the Physical Integrity Index from Cingranelli et al. (2014). This index is constructed from variables on torture, extrajudicial killing, political imprisonment, and disappearances, and ranges from 0-8, with higher scores indicating better human rights performance. As noted, the TSCS structure of our data allows us to examine the effects of democracy aid shocks across countries, as well as their impact on human rights right performance within a country (i.e., pre- and post-shock human rights performance).

For our central explanatory variable – civil society democracy aid shock – we rely on the AidData 3.1 dataset (Tierney et al. 2011), which includes commitments of OECD member development assistance by individual project and project purpose. We select US aid and aggregate it to the annual, country-level commitments by purpose, differentiating between democracy assistance and other development aid with AidData 3.1 project codes. We identify purpose codes 15000-15199 – ‘governance and civil society’ aid – as democracy assistance, and all others as general foreign aid. We use the AidData project codes to differentiate between aid packages for civil society organizations and other democracy aid (mostly targeted to executive, legislative and judicial institutions, government and program administration, and economic institutions). Civil society democracy aid constitutes about 30-40% of US democracy assistance annually during the period of our study, and takes a great many forms ranging from training program to capacity building, program support, support for infrastructure, and organizational support, all designed to empower and expand the activities and influence of the civil society organizations (e.g., see, Collins 2009; Dietrich 2013; Dietrich and Wright 2015; Finkel et al. 2007; Hearn 2000; Kalyvitis and Vlachaki 2010.

From this, we strictly follow and apply Nielsen et al. (2011, 224) to construct the civil society democracy aid shock measure:

To measure aid shocks, we begin by calculating the change in aid (standardized by GDP) for each country-year (aid/GDPt— aid/GDPt−1).12 We average changes over the previous two years to account for the time gap between aid commitments and the time at which countries actually receive (or fail to receive) the aid…. Using commitment data, we then define the bottom 15% of these aid changes to be Aid Shocks—negative changes that are large enough that we expect them to have a potentially destabilizing effect on recipients.

We measure these civil society democracy aid shocks dichotomously and, in our simultaneous equation models, in constant 2009 dollars for one of the reciprocal processes.5

Controls. We include a series of control measures, which reflect the findings of previous studies of the determinants of the human rights repression, and the allocation of foreign and democracy assistance and stem from our discussion in the preceding section. Diagnostics indicate collinearity among these variables is not a concern.

In our GLS models we include five control measures. First, we control for regime type, to account for the relationship between human rights performance and the level of democracy/autocracy of a regime. We use the Polity IV measure of democracy-autocracy (Marshall and Jaggers 2012), while acknowledging its limitations (e.g. Munck and Verkuilen 2002).6 Second, we include a control for general aid commitments to account for the potential impact of general foreign aid on human rights performance, subtracting democracy aid from total aid to obtain a measure of ‘other aid’, and including its logarithm in constant 2009 dollars (see Peterson and Scott 2018; Scott and Carter 2019; Scott, Rowling and Jones 2020).7 Third, we control for trade integration with a measure of the volume of US trade (sum of exports from and imports to the US) to account for the potential impact of economic integration with a potential recipient in current dollars (Barbieri and Keshk 2012). Fourth, we control for recipient economic conditions with per capita gross domestic product in current dollars for each country-year (data from the Penn World Tables) to account for the potential relationship between wealth/poverty and human rights. Finally, we control for the effects of violent civil conflict to account for the potential impact of armed conflict within the recipient state on human rights, using the Major Episodes of Political Violence data from the Center for Systemic Peace (Marshall 2016).8 For each country-year, from this data we identify countries involved in civil or intrastate conflict, coding dichotomously.

We begin with descriptive and bivariate data on to provide the context and summary information on democracy aid shocks and their occurrence, and the simple correlations between these shocks and human rights conditions. Then, we test our argument with two different techniques, which enable us to account for shocks driven by changing priorities (GLS models) and shocks driven by aid conditionality calculations (simultaneous equation models). Together, they increase our confidence in results of our findings on the impact of democracy aid shocks on human rights performance.9

We first use generalized least squares models with random effects, appropriate to the time-series cross-sectional data of our study (e.g., Beck 2009). For our analysis, random effects estimators have the advantage of taking into account both the uniqueness of each country and the effect of time, while fixed effects models exploit within-group variation over time. However, although we believe that random effects are appropriate for our analysis, we also test our GLS models with fixed effects where across-country variation is not used to estimate the models. We also test GLS models with a lagged dependent variable (LDV) to account for the autoregressive process in the dependent variable (human rights conditions).

Second, in order to account for the reciprocal process by which changes in human rights performance could affect democracy aid decisions in the first place (as our discussion of aid decisions, conditionality, and feasibility suggested), which then have an effect on human rights performance, we test a simultaneous equation model to examine the links between civil society aid shocks and human rights performance as simultaneous processes. Use of this technique enables us to gauge the impact of the civil society aid shocks on human rights while measuring and controlling for the effects of nascent human rights repression on the allocation of civil society democracy aid.

We model the aid shock-human rights and human rights-aid shock links as integrated processes with two endogenous equations (e.g., Reuveny and Li 2003; Keshk, Pollins, and Reuveny 2004; see also Scott and Steele 2011). One equation models the allocation of civil society democracy aid as a function of the human rights performance of the target regime and other factors, and the second equation represents the impact of civil society democracy aid shocks on the human rights performance of the target regime.

In the first process/equation, we model civil society democracy allocations as a function of the recipient state’s human rights performance, recipient regime type, recipient wealth (GDP per capita), US political interests, US alliances, trade with the US, and other aid from the US on the allocation of US civil society democracy aid. To measure US political interests, we rely on Strezhnev and Voeten’s (2013) political affinity scores (s-score), which are based on UN General Assembly voting data. In these scores, political affinity is measured by an index ranging from -1 to 1, with higher scores indicate similar voting – and thus affinity – between a potential recipient and the US. For US alliances, we simply code a dichotomous measure for the presence of an alliance between a potential recipient and the US for each country year using Correlates of War Alliance data (Gibler 2009). Our measures for the other variables are the same as described in the GLS models. In the second process, we control for the effects of civil society democracy aid shocks, recipient regime type, recipient wealth (GDP per capita), conflict (political violence/civil war in the target state), trade with the US, and other aid on the human rights performance of the target recipient. Our measures for this are as previously discussed.

We accomplish the identification of the simultaneous equation mode through the exclusion condition (Greene 1997), as each equation contains at least one variable not found in the other equation. For the civil society democracy aid allocation equation, these variables are US interests and US alliances, and for the human rights equation, this variable is conflict. Of course, the first process includes human rights as an explanatory variable, and the second process includes civil society democracy aid shocks as an explanatory variable.

In both the GLS and SEM techniques, we test models for both measures of the dependent variable (PTS and Physical Integrity Index). In all models, we lag independent variables by one year to ensure time order, and in the SEM models, we lag the second process a year behind the first process to ensure that we are gauging how human rights affects civil society democracy aid allocations at time t and how civil society aid allocations affect human rights at time t+1. We derive our results with STATA, version 14.

RESULTS

For context, Figure 1 shows US democracy aid allocations from 1975-2013. As shown, about the time of the end of the Cold War, US democracy aid surged from low levels in the 1970s and 1980s, especially after 1999, when new commitments during the Global War on Terror led to expanded assistance (see also Scott and Carter 2019). In practical terms, US democracy aid reached substantively significant amounts after 1982, when our analysis begins, so the limit to the start date necessitated by other data restrictions is not problematic.

Figure 1: US Democracy Aid, 1975-2013

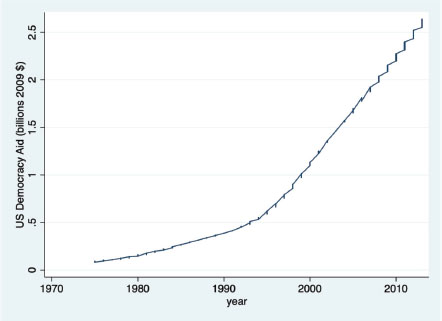

Our key explanatory variable is civil society democracy aid shock. Table 1 presents basic descriptive information about the nature of democracy aid and these aid shocks. For the period of our study, average annual GDP-weighted civil society democracy aid amounted to thirteen cents. Applying the Nielsen et al. (2011, 224) formula for measuring aid shock, our civil society democracy aid shock variable shows an average reduction of eleven cents for civil society democracy aid, which is an 85% decrease to average civil society democracy aid. This dramatic reduction clearly warrants the “shock” label. These shocks are broadly distributed across regime type, as Figure 2 shows, with somewhat greater frequency in the -6 to -7 and 5 to 6 levels of the Polity score, but they are, not surprisingly, more frequent as the years pass and the amount and recipients of US democracy aid increase.

Table 1: Democracy Aid and Aid Shocks

Democracy Aid Variable |

GDP-Weighted Aid Avg |

GDP-Weighted Shock Avg |

Civil Society Democracy Aid |

.13 |

-.11 |

Figure 2: Frequency of Democracy Aid Shocks By Regime Type (Polity score) and Year

With this context in mind, Table 2 shows bivariate correlations between civil society aid shocks and regime human rights performance, measured by the Cingranelli et al. (2014) Physical Integrity Index, where higher values indicate better human rights performance, and the Gibney et al. (2013) Political Terror Scale (inverted as noted). As the data in Table 2 show, there is a modest, but meaningful correlation in the expected direction: civil society democracy aid shocks are related to lower human rights performance the following year. These results provide good initial support for our hypothesis. Simple bivariate correlations also suggest that we need not be concerned with aid substitution effects in which democracy aid shocks are paired with increases to other forms of aid, that shocks to civil society democracy aid are paired with increases to democracy aid to institutions, or vice versa. Indeed, other US aid and democracy aid overall and civil society democracy aid more narrowly, as well as civil society democracy aid and institutional democracy aid correlate positively. However, they also correlate only modestly in both instances, indicating that the flows of general foreign aid and democracy aid move separately.

Table 2: Correlations Between Aid Shocks and Human Rights

Aid Shock |

Physical Integrity Index |

Political Terror Scale |

Civil Society Aid Shock |

-.13 |

-.15 |

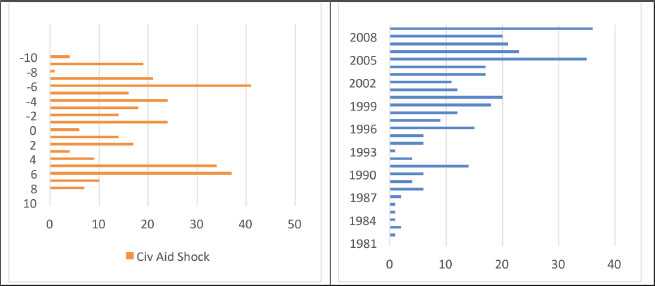

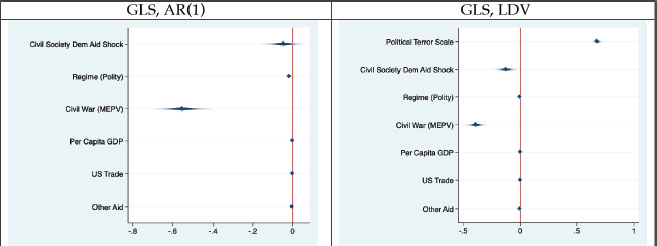

Table 3 presents the tests of our argument using GLS random effects models. As the results in this table show, our data provides strong support for our theorized effect: civil society democracy aid shocks are associated with worse subsequent human rights performance. For our control variables, civil war, poverty, and trade consistently show a negative relationship with human rights performance. Regime type and other US aid are less consistent, reaching statistical significance in one (regime type) or two (other aid) of the models.

After controlling for these factors, our results show substantial support for the general democracy aid shock – human rights relationship. In three of the four models – including both with lagged dependent variables – civil society democracy aid shocks are associated with declines in both measures of human rights performance (PTS and PHYSINT). The results indicate that a democracy aid shock leads to about 2.5% - 2.8% decline in human rights performance the year following the aid shock. Overall, this demonstrates varying support that states facing the onset of democracy aid shocks are likely to engage in more repressive behavior against their citizens.

Table 3: Civil society democracy aid shocks and human rights performance, 1982-2013 Random Effects Models

IVs |

Political Terror Scale Models |

Physical Integrity Index Models |

||

GLS |

GLS + LDV |

GLS |

GLS + LDV |

|

|

Constant LDV Civil Society Aid Shock Regime Type Civil War GDP Per Capita Trade Other Aid |

3.4 (.08)*** -- -.05 (.04) -.02 (.006)*** -.55 (.06)*** .00001 (.000004)*** -.000003 (.000001)*** -.002 (.003) |

1.1 (.07)*** .68 (.02)***-- -.12 (.04)*** -.0004 (.003) -.39 (.04)*** .000008 (.000002)*** .000001 (.0000005)* .001(.002) |

4.36 (.18)*** -- -.22 (.08)*** -.0003 (.01) .-1.05 (.12)*** .00003 (.000009)*** -.000007 (.000002)*** .-.01 (.007)* |

1.74 (.13 )*** .63 (.02)***-- -.23 (.08)*** .004 (.006) -.70 (.08)*** .00001 (.000004)*** -.000004 (.000001)*** -.01 (.005)** |

|

N=2055 Wald Chi2=132.14 R2 Overall = .36 R2 Between= .54 |

N=2029 Wald Chi2=4090.46 R2 Overall = .67 R2 Between= .96 |

N=1938 Wald Chi2=110.32 R2 Overall = .33 R2 Between= .52 |

N=1857 Wald Chi2=2437.73 Overall = .63 R2 Between= .93 |

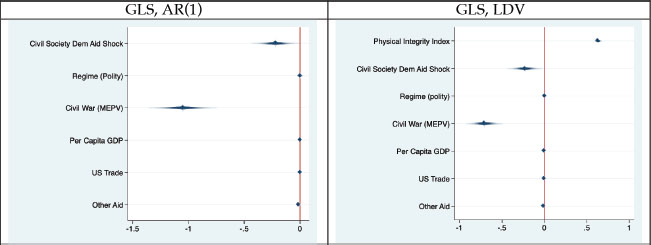

Figures 3-4 graphically portray the point estimates of these results. Figure 3 includes the results of the Political Terror Scale models, and Figure 4 includes those of the Physical Integrity Rights models. In both, the statistically significant, negative effects of civil society aid shocks stand out.

Figure 3: Point Estimates of Civil Society Aid Shocks and Controls on Political Terror Scale, with 95% Confidence Intervals.

Figure 4: Point Estimates of Civil Society Aid Shocks and Controls on Physical Integrity Index, with 95% Confidence Intervals.

Table 4 presents the results of the GLS models using fixed effects, which controls for the unique characteristics of each individual country in our sample and emphasizes within-country variation over time. That is, Table 4 results show the relationships between civil society democracy aid shocks and human rights performance focusing on pre- and post-shock human rights performance within each country. As the results in the table indicate, these models show further support for the general democracy aid shock – human rights relationship. In all four fixed effects models – including both with lagged dependent variables – even with across-country variation omitted, civil society democracy aid shocks are associated with declines in both measures of human rights performance after the shock (Political Terror Scale and Physical Integrity Index) after the shock. The size of the impact is comparable to those seen in the random effects models. Overall, this further supports our argument that states experiencing democracy aid shocks are likely to engage in more repressive behavior against their citizens.

Table 4: Civil society democracy aid shocks and human rights performance, 1982-2013 Fixed Effects Models

|

Political Terror Scale Models |

Physical Integrity Index Models |

||

GLS |

GLS + LDV |

GLS |

GLS LDV |

|

Constant |

3.047*** (.032) |

1.64*** (.083) |

3.913*** (.079) |

2.356*** (.151) |

LDV |

|

.521*** (.019) |

|

.473*** (.021) |

Civil Society Aid Shock |

-.03 (.043) |

-.10** (.042) |

-.20** (.084) |

-.25*** (.084) |

Regime Type |

.012* (.006) |

-.009** (.004) |

.045*** (.012) |

.001 (.008) |

Civil War |

-.343*** (.061) |

-.373*** (.044) |

-.596*** (.131) |

-.583*** (.095) |

GDP Per Capita |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

Trade |

0* (0) |

0** (0) |

0* (0) |

0** (0) |

Other Aid |

.007** (.003) |

0 (.003) |

-.005 (.007) |

-.009 (.006) |

Observations |

1952 |

2029 |

1836 |

1857 |

As a final check, we tested models using the effects of general democracy aid shocks and institutional democracy aid shocks (the first using aggregate democracy assistance, the second using democracy assistance to executive, legislative and judicial institutions, government and program administration, and economic institutions, or non-civil society democracy aid). Our appendix contains the core results of these tests, which show that, unlike civil society democracy aid shocks, these other types of shocks do not affect human rights performance in a statistically significant manner. This further increases our confidence in our argument and our emphasis on civil society democracy aid shocks as the likely trigger for increased repression by a regime. 10

Hence, the results of the GLS models provide strong support for our argument. Consistent with the logic of our theory, sudden reductions of civil society democracy aid are associated with negative effects on human rights. The combination of our GLS models indicates that: a) states experiencing civil society democracy aid shocks engage in greater repression after the shock than before it; b) states experiencing civil society democracy aid shocks engage in greater repression after the shock than countries that do not experience such shocks. In short, repression by the state increases when democracy aid is slashed. The signals and weakening effects of such shocks appear to embolden regimes to engage in greater repression.

However, as our argument noted, civil society aid shocks themselves may occur in part in response to deteriorating human rights performance in an aid recipient. Hence, we must address this potential reciprocal relationship, and we do so through the use of simultaneous equation models, as we previously discussed. These models enable us to account for the reciprocal process by which changes in human rights performance could prompt civil society democracy aid shocks in the first place, and to better gauge the subsequent effects of those shocks on human rights performance in that context.

Table 5 presents the results of the simultaneous equation models testing our argument. The upper half of the table presents the results of the aid process – the effects of human rights on civil society aid allocations. As these results indicate, after controlling for other factors including US political and strategic interests, level of development, and economic relationships between the US and a potential recipient, lower human rights scores are associated with declining civil society democracy aid amounts and the relationship is statistically significant. In practical terms, each point decrease in the human rights indices is associated with $800,000 (PHYSINT) - $12 million (PTS) less in civil society democracy aid (constant 2009 $).

Table 5: Simultaneous equation models of civil society democracy aid, shocks, and human rights performance, 1982-2013.

IVs |

Political Terror Scale |

Physical Integrity Index |

Aid Process |

|

|

|

Constant Political Terror Scale Regime Type US Political Interests US Ally GDP Per Capita Trade Other Aid |

1839653 (1609995) -12228980*** (344706) 36504 (69791) -2643767* (1603616) -25374.47 (1049509) 42.61 (43.64) 14.24 (14.62) 201873* (48805) |

-2579748 (2120405) -814406*** (239942) -4035 (95011) -7562582*** (2706775) 768945 (1500992) 67.8 (63.1) 2.0 (16.7) 3617773*** (78631) |

|

N=1844 RMSE=1.36e+07 R2=.03 P=.000 |

N=1781 RMSE=1.93e+07 R2=.32 P=.000 |

Human Rights Process |

|

|

|

Constant Civil Society Aid Shock Regime Type Civil War GDP Per Capita Trade Other Aid |

3.6*** (.06) -.37*** (.06) -.01** (.004) -1.2*** (.004) .00002*** (.000002) -.000003 *** (.0000008) -.01*** (.003) |

4.72*** (.12) -.56*** (.11) .008 (.008) -2.09*** (.09) .00004*** (.000005) -.00001*** (.000001) -.025***. (.007) |

|

N=1844 RMSE=.8 R2=.38 P=.000 |

N=1781 RMSE=1.68 R2=.32 P=.000 |

We focus on the bottom half of the table for the most important assessment of our argument. In the human rights process – the effects of civil society aid shocks on human rights performance – our results strongly support our argument. Even after controlling for the effects of human rights on civil society democracy aid allocations, subsequent civil society democracy aid shocks appear to produce significant and substantive reductions of human rights performance by the regime. Like the GLS models, this relationship is robust across both measures of human rights. In practical terms, the relevant coefficients indicate that a civil society democracy aid shock is associated with a 7 - 7.5% deterioration in a regime’s human rights performance in the year after the shock. These results are even stronger than those using the GLS techniques and improve our confidence in the theorized relationship, especially considering that they hold even when factoring in potential reciprocal effects of human rights changes on aid allocations themselves. Put simply, it does not appear to be the case that the relationship between civil society democracy shocks and human rights performance is an artifact of deteriorating human rights conditions affecting aid allocations: instead, as we theorized, repression by the state increases when democracy aid is slashed. The weakening of civil society actors and their support and the signals such shocks provide to the appear to embolden regimes to engage in greater repression.

CONCLUSION

The literature on democracy aid has focused on why it is allocated to some recipients and not others, and how such aid affects democratization. Far less attention has been devoted to the question of what occurs when democracy aid is suddenly halted. Our examination of these democracy aid shocks finds further evidence supporting the efficacy of democracy assistance and highlights the harmful effects of its abrupt reduction. Overall, our evidence indicates that human rights generally worsen when US civil society democracy aid is suddenly reduced. Importantly, as other studies have concluded (e.g., Dietrich and Wright 2015; Ottaway and Carothers 2000), the US funds civil society organizations to empower them to advocate for, participate in, and achieve democratization, and democracy assistance appears to be a positive contributor to democratization (e.g., Askarov and Doucouliagos 2013; Dietrich and Wright 2015; Finkel et al. 2007; Heinrich and Loftis 2017; Kalyvitis and Vlachaki 2010; Scott and Steele 2011). Our analysis indicates that when US democracy aid to civil society groups is cut, the ruling regime may be incentivized to engage in repression, causing a worsening human rights situation because the regime sees it as an opportunity – even a signal – to quash pressure for and progress toward democratization.

Our findings have important policy implications. Not only does democracy aid appear to contribute to progress toward democracy and improved human rights, performance as other studies have shown, its sudden reduction, particularly in cuts to civil society aid shocks, appears to contribute to significant reversals to human rights protections. The worsening situations appear to lead to increases in torture, extrajudicial killing, and political imprisonment, which are the principal forms of human rights repressions captured in the measures we use for our dependent variable. As such, democracy aid shocks affect regime behavior and human security. Moreover, in policy terms, the apparent consequences of democracy aid shocks in the human rights behavior of recipients are likely to lead to subsequent difficult policy decisions for donors. Among these are hard choices about whether and how to reestablish, resume, and rebuild democracy aid to reverse the deterioration of human rights in the recipient state in the face of the regime’s increased repression, and/or to engage in other, potentially even more costly responses to address the human rights situation. Importantly, the unintended consequences of democracy aid shocks on human rights performance and the ensuing policy dilemmas should caution donor states when considering the sudden withdrawal of democracy assistance.

Our analysis also suggests several avenues for further research. First, our analysis focuses on US democracy assistance. Incorporating non-US donors, both individually and in aggregate studies of OECD and other multilateral democracy aid, for example, would further illuminate the relationship between democracy aid, aid shocks, and human rights performance, and would enable examination of the potential for aid substitution effects among other donors as well. Other potential substitution effects also merit attention in subsequent studies, including those related to shifts between democracy aid and other types of assistance, and those among different subcategories of democracy assistance itself (e.g., civil society vs. institutional, as well as the more specific rule of law and human rights, good governance, political competition and electoral processes, and civil society and political participation subcategories).

Second, other areas of focus and techniques of analysis might shed additional light on the relationship our findings suggest. Comparing sudden democracy aid reductions with gradual democracy aid declines might shed further light on the impact of reductions, while examining both positive and negative aid shocks and unpacking threats of reductions from actual reductions might reveal additional nuances in the relationship. Moreover, our argument rests on the insights of studies of foreign and democracy assistance allocation stressing the effects of donor interests, recipient needs, humanitarian and ideational purposes, feasibility, and other determinants on decisions to provide, suspend, reduce, or eliminate aid. However, the range of calculations and processes that produce democracy aid shocks – both deliberate and less intentional - warrants further attention to examine potential variance in the consequences of aid shocks stemming from this range of processes. Further, additional efforts to examine the potential endogeneity of the relationship between human rights repression and democracy aid shocks would further test the nature and robustness of the relationship our study has identified. Numerous techniques might be employed to do so, including the use of an instrumental variables approach.

Finally, judicious use of process-tracing case studies might help to examine and develop the causal sequences linking decisions to reduce democracy aid to subsequent human rights practices in recipient states. They would also enable further attention to the potentially interesting substitution effects outlined above. But, at a time in which the more-than-three-decade old commitment by the US to provide democracy aid to promote democratization in targeted recipients is under increasing threat, our analysis suggests that such actions would have significant, and negative, consequences in the lives and well-being of many people.

REFERENCES

Alesina, A. and D. Dollar. 2000. Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why. Journal of Economic Growth 5: 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009874203400

Apodaca, C. 2017. Foreign Aid as Foreign Policy Tool. Oxford Research Encyclopedia, Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.332

Apodaca, C. and M. Stohl. 1999. United States Human Rights Policy and Foreign Assistance. International Studies Quarterly 43: 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/0020-8833.00116

Askarov, Z. and H. Doucouliagos 2013. Does Aid Improve Democracy and Governance? A Meta-regression Analysis. Public Choice 157: 601–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0081-y

Balla, E and G. Y. Reinhardt. 2008. Giving and Receiving Foreign Aid: Does Conflict Count? World Development 36: 2566–2585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.03.008

Barbieri, K. and O. M. G. Keshk 2012. Correlates of War Project Trade Data Set Codebook, version 3.0. Online: http://correlatesofwar.org.

Bearce, D. and D. Tirone. 2010. Foreign Aid Effectiveness and the Strategic Goals of Donor Governments. Journal of Politics 72: 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000204

Beck, N. 2009. Time-Series-Cross-Section Methods. In Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by Janet Box-Steffensmeier, Henry E. Brady, and David Collier. London: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199286546.003.0020

Bermeo, N. 2016. On Democratic Backsliding. Journal of Democracy, 27(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0012

Blanton, S.L. 2005. Foreign Policy in Transition: Human Rights, Democracy, and U.S. Arms Exports. International Studies Quarterly. 49: 647-667.

Boutton, A. and D. Carter. 2014. Fair-Weather Allies? Terrorism and the Allocation of US Foreign Aid. Journal of Conflict Resolution 58: 1144–1173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002713492649

Braithwaite, J. M and A. Licht. 2020. The Effect of Civil Society Organizations and Democratization Aid on Civil War Onset. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 64: 1095–1120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002719888684

Bridoux, J. and M. Kurki. 2014. Democracy Promotion: A Critical Introduction. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203796511

Bueno do Mesquita, Bruce, George Downs, Alastair Smith and Feryal Marie Cherif. 2005. Thinking inside the box: a closer look at democracy and human rights. International Studies Quarterly. 49: 439–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2005.00372.x

Burnside, C. and D. Dollar. 2000. Aid, Policies and Growth. American Economic Review 90: 847- 868. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.4.847

Cingranelli, David L. and Thomas E. Pasquarello. 1985. Human rights practices and the distribution of U.S. foreign aid to Latin American countries. American Journal of Political Science. 29: 539–563. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111142

Cingranelli, D.L., D.L. Richards, and K. C. Clay. 2014. "The CIRI Human Rights Dataset." http://www.humanrightsdata.com. Version 2014.04.14.

Collins, S.D. 2009. Can America finance freedom? Assessing U.S. democracy promotion via economic statecraft. Foreign Policy Analysis 5: 367–389. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-8594.2009.00098.x

Cortright, D., and Lopez, G.A. (eds.) (1995) Economic Sanctions: Panacea or Peacebuilding in a Post-Cold War World? Boulder, CO: Westview.

Cortright, D., and Lopez, G.A. (eds.) (2000) The Sanctions Decade: Assessing UN Strategies in the 1990s. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Cortright, D., and Lopez, G.A. (eds.) (2002) Smart Sanctions: Targeting Economic Statecraft. New York: Rowman Littlefield.

Crawford, G. 1997. Foreign aid and political conditionality: Issues of effectiveness and consistency. Democratization. 4:3, 69–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510349708403526

Dasandi, N., & Erez, L. 2017. The Donor’s Dilemma: International Aid and Human Rights Violations. British Journal of Political Science, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000229

Davenport, C. 2007. State Repression and Political Order. Annual Review of Political Science. 10:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.101405.143216

Dietrich, S. 2013. Bypass or Engage? Explaining Donor Delivery Tactics in Foreign Aid Allocations. International Studies Quarterly 57 (4): 698–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12041

Dietrich, S. 2016. Donor Political Economies and the Pursuit of Aid Effectiveness. International Organization. 70: 65–102. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818315000302

Dietrich, S. and J. Wright. 2015. Foreign Aid Allocation Tactics and Democratic Change in Africa. Journal of Politics 77: 216–34. https://doi.org/10.1086/678976

Djankov, S., Montalvo, J. Go, and Reynal-Querol, M. 2009. Aid with Multiple Personalities. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2008.09.005

Drury, A. C., R. Olson, D. Van Belle D. 2005. The CNN effect, geo-strategic motives and the politics of U.S. foreign disaster assistance. Journal of Politics 67: 454–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00324.x

Dunning, T. 2004. Conditioning the Effects of Aid: Cold War Politics, Donor Credibility, and Democracy in Africa. International Organization, 58(2), 409–423. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818304582073

Dupuy, K., Ron, J., Prakash, A. 2016. Hands Off My Regime! Governments’ Restrictions on Foreign Aid to Non-Governmental Organizations in Poor and Middle-Income Countries. World Development, 84, 299–311.

Findley, M. 2018. Does Foreign Aid Build Peace? Annual Review of Political Science. 21:359–384. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-015516

Finkel, S. 2003. Can Democracy Be Taught? Journal of Democracy 14: 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2003.0073

Finkel, S., A. Perez-Linan, M.A. Seligson. 2007. The effects of U.S. foreign assistance on democracy-building, 1990-2003. World Politics 59: 404–439. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100020876

Gazibo, M. 2013. Beyond Electoral Democracy: Foreign Aid and the Challenge of Deepening Democracy in Benin. In Democratic Trajectories in Africa: Unravelling the Impact of Foreign Aid, eds. Danielle Resnick and Nicolas van de Walle. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 228–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199686285.003.0009

Gibler, D.M. 2009. International military alliances, 1648-2008. Washington, DC: CQ Press. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781604265781

Gibney, M., Cornett, L., Wood, R., & Haschke, P. 2013. Political Terror Scale 1976-2012. Available from: http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/.

Girod, D. 2018. The Political Economy of Aid Conditionality. Oxford Research Encyclopedia, Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.59

Girod, D and J. Tobin. 2016. Take the Money and Run: The Determinants of Compliance with Aid Agreements. International Organization. 70:1, 209–239. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818315000326

Greene, W.H. 1997. Econometric Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gutting, R. and M.C. Steinward. 2015. Donor Fragmentation, Aid Shocks, and Violent Political Conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 61:3, 643–670. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715595701

Gyimah-Boadi, E., M. Oquaye, and K. Drah 2000. Civil Society Organizations and Ghanaian Democratization. Research Report 6. Accra: Centre for Democracy and Development.

Gyimah-Boadi, E. and M. Oquaye. 2000. Civil Society and the Domestic Policy Environment in Ghana. Research Report 7. Accra: Centre for Democracy and Development.

Gyimah-Boadi, E., and Theo Yakah. 2013. Ghana: The Limits of External Democracy Assistance. In Democratic Trajectories in Africa: Unravelling the Impact of Foreign Aid, eds. Danielle Resnick and Nicolas van de Walle. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 256–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199686285.003.0010

Hearn, J. 2000. Foreign Political Aid, Democratization and Civil Society in Ghana in the 1990s. Working Paper 5. Accra: Centre for Democracy and Development.

Heinrich, Tobias. 2013. When is foreign aid selfish, when is it selfless? Journal of Politics 75(2): 422–435. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002238161300011X

Heinrich, T. and M.W. Loftis. 2017. Democracy Aid and Electoral Accountability. Journal of Conflict Resolution. 63: 139–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002717723962

Heinrich, T., Y. Kobayashi and L. Long. 2018. Voters Get What They Want (When They Pay Attention): Human Rights, Policy Benefits, and Foreign Aid. International Studies Quarterly. 62: 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx081

Hufbauer, G.C., Schott, J.J., Elliott, K.A., and Oegg, B. (2007) Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. 3rd edn. Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics.

Hultman. L. and D. Peksen. 2017. Successful or Counterproductive Coercion? The Effect of International Sanctions on Conflict Intensity. Journal of Conflict Resolution. Volume: 61:6, 1315–1339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715603453

Kalyvitis, S. and I. Vlachaki. 2010. Democratic Aid and the Democratization of Recipients. Contemporary Economic Policy 28: 188–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7287.2009.00154.x

Keshk, Omar M.G., Brian M. Pollins, and Rafael Reuveny. 2004. Trade Still Follows the Flag: The Primacy of Politics in a Simultaneous Model of Interdependence and Armed Conflict. Journal of Politics, 66: 1155–1179.

Knack, S. 2004. Does Foreign Aid Promote Democracy? International Studies Quarterly, 48: 251-266.

Marshall, M. 2016. Major Episodes of Political Violence (MEPV) And Conflict Regions, 1946-2015. Center for Systemic Peace: www.systemicpeace.org.

Marshall, M. and K. Jaggers 2012 Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2011, http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm.

McKinlay, R.D. and R. Little. 1977. A foreign policy model of US bilateral aid allocation. World Politics, 30: 58–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/2010075

Meernik, J., E.L. Krueger and S.C. Poe. 1998. Testing Models of U.S. Foreign Policy: Foreign Aid During and After the Cold War. Journal of Politics, 60: 63–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/2648001

Mitchell, L.A. 2016. The Democracy Promotion Paradox. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Montinola, G.R. 2010. When Does Aid Conditionality Work? Studies in Comparative International Development. 45: 358–382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-010-9068-6

Morgenthau, H. 1962. A Political Theory of Foreign Aid. American Political Science Review, 56(2), 301–309. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952366

Munck, G. and J. Verkuilen. 2002. Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: Evaluating Alternative Indices. Comparative Political Studies 35: 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/001041400203500101

Nielsen, R. 2013. Rewarding Human Rights? Selective Aid Sanctions against Repressive States. International Studies Quarterly. 57: 791–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/isqu.12049

Nielsen, R. and D. Nielson. 2010. Triage for democracy: Selection effects in governance aid. Paper presented at the Department of Government, College of William & Mary, 5 February 2010.

Nielsen, R,. M. Findley, Z. Davis, T. Candland, and D. Nielson. 2011. Foreign Aid Shocks as a Cause of Violent Armed Conflict. American Journal of Political Science. 55:2, 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00492.x

Noorbakhsh, F and Paloni, A. 2007. Learning from Structural Adjustment: Why Selectivity May Not be the Key to Successful Programmes in Africa. Journal of International Development: The Journal of the Development Studies Association, 19(7), 927–948. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1357

Ottaway, Marina, and Thomas Carothers. (2000) Funding Virtue: Civil Society Aid and Democracy Promotion. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Peksen, D. 2009. Better or Worse? The Effect of Economic Sanctions on Human Rights. Journal of Peace Research. 46:1, 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343308098404

Peterson, T. and J. M. Scott. 2018. The democracy aid calculus: Regimes, political opponents, and the allocation of US democracy assistance, 1975-2009.” International Interactions. 44: 268–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2017.1339701

Plumper, T. and E. Neumayer. 2010. The Level of Democracy during Interregnum Periods: Recoding the polity2 Score. Political Analysis 18: 206–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpp039

Poe, S.C. 1992. Human rights and economic aid allocation under Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter. American Journal of Political Science, 36: 147-167.

Poe, Steven C. and Neal Tate. 1994. Repression of human rights to personal integrity in the 1980s: a global analysis. American Political Science Review, 88:4, 853–872. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082712

Powell, Robert. 2006. War as a Commitment Problem. International Organization 60:1, 169–203.

Reinsberg, B. 2015. Foreign Aid Responses to Political Liberalization. World Development 75: 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.11.006

Reuveny, Rafael, and Quan Li. 2003. The Joint Democracy-Dyadic Conflict Nexus: A Simultaneous Equations Model. International Studies Quarterly, 47: 325–346.

Robinson, M. and S. Friedman. 2007. Civil Society, Democratization, and Foreign Aid: Civic Engagement and Public Policy in South Africa and Uganda. Democratization, 14: 643–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510340701398329

Savun, B. and D. Tirone. 2011. Foreign Aid, Democratization, and Civil Conflict: How Does Democracy Aid Affect Civil Conflict? American Journal of Political Science. 55: 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00501.x

Savun, B. and D. Tirone. 2012. Exogenous Shocks, Foreign Aid, and Civil War. International Organization. 66:3, 363–393. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818312000136

Schraeder, P.J., S.W. Hook, and B. Taylor. 1998. Clarifying the Foreign Aid Puzzle: A Comparison of American, Japanese, French, and Swedish Aid Flows. World Politics 50: 294 – 323.

Scott, J.M. 2012. Funding Freedom? The United States and US Democracy Aid in the Developing World, 1988-2001. In Liberal Interventionism and Democracy Promotion, Dursun Peksen, Editor. New York: Lexington/Rowman-Littlefield, 13–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.877893

Scott, J.M and R.G. Carter. 2015. From Cold War to Arab Spring: Mapping the Effects of Paradigm Shifts on the Nature and Dynamics of U.S. Democracy Assistance to the Middle East and North Africa. Democratization, 22:4 (June 2015), 738–763.

Scott, J.M. and R.G. Carter. 2016. Promoting Democracy in Latin America: Foreign Policy Change and US Democracy Assistance, 1975-2010. Third World Quarterly. 37: 299–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1108824

Scott, J.M. and R.G. Carter. 2019. Distributing dollars for democracy: Changing foreign policy contexts and the shifting determinants of US democracy aid, 1975-2010. Journal of International Relations and Development. 22:3, 640–675. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-017-0118-9

Scott, J.M. and R.G. Carter. 2020. Democratizing Dictators? Non-Democratic Regime Conditions and the Allocation of US Democracy Assistance, 1975-2010.” International Political Science Review, 41:3 (June 2020): 436–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512119858358

Scott, J.M, C.M. Rowling and T. Jones. 2019. Democratization, Security Interests, and Country Visibility: The Conditional Effects of Democratic Change, Strategic Interests, and Media Attention on US Democracy Aid, 1975-2010. Paper presented at the Conference on Globalization, Security and Ethnicity (International Political Science Association), Nagasaki, Japan, August 10–11, 2019.

Scott, J.M, C.M. Rowling and T. Jones. 2020. Democratic Openings and Country Visibility: Media Attention and the Allocation of US Democracy Aid, 1975-2010. Foreign Policy Analysis 16(3): 373–396. https://doi.org/10.1093/fpa/orz023

Scott, J.M. and C.A. Steele. 2011. Sponsoring democracy: The United States and democracy aid to the developing world, 1988-2001. International Studies Quarterly 55(1): 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2010.00635.x

Strezhnev, A. and E. Voeten. 2013. United Nations General Assembly Voting Data. http://hdl.handle.net/1902.1/12379 UNF:5:s7mORKL1ZZ6/P3AR5Fokkw== Erik Voeten [Distributor] V7 [Version].

Temple, J.R.W. 2010. Aid and conditionality. Handbook of Development Economics, Volume 5, edited by Dani Rodrik and Mark Rosenzweig. London: Elsevier, 4415–4523. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-52944-2.00005-7

Tierney, M., D. Nielson, D. Hawkins, J. Roberts, M. Findley, R. Powers, B. Parks, S. Wilson, and R. Hicks. 2011. More Dollars than Sense: Refining Our Knowledge of Development Finance Using AidData. World Development (November). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.029

Yiew, T. H., & Lau, E. 2018. Does foreign aid contributes to or impede economic growth. Journal of International Studies, 11:3, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-8330.2018/11-3/2

Received: July 3rd 2021

Accepted: October 28th 2021

APPENDIX

GENERAL DEMOCRACY AID SHOCKS, INSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY AID SHOCKS, AND HUMAN RIGHTS PERFORMANCE, 1982-2013, GLS WITH RANDOM EFFECTS

|

Physical Integrity Index |

Physical Integrity Index |

Political Terror Scale |

Political Terror Scale |

General Democracy Aid Shock |

-.042 (.08) |

|

-.003 (.038) |

|

Institutional Democracy Aid Shock |

|

-.064 (.078) |

|

-.039 (.038) |

Regime Type |

-.002 (.011) |

-.002 (.011) |

-.017*** (.006) |

-.017*** (.006) |

Civil War |

-1.043*** (.118) |

-1.048*** (.118) |

-.55*** (.055) |

-.554*** (.055) |

GDP Per Capita |

0*** (0) |

0*** (0) |

0*** (0) |

0*** (0) |

Trade |

0*** (0) |

0*** (0) |

0*** (0) |

0*** (0) |

Other US Aid |

-.013* (.007) |

-.013* (.007) |

-.002 (.003) |

-.002 (.003) |

Constant |

4.336*** (.169) |

4.341*** (.168) |

3.203*** (.072) |

3.209*** (.072) |

Observations |

1938 |

1938 |

2055 |

2055 |

|

Overall R2 Within R2 Between R2 |

.32 .08 .51 |

.32 .08 .51 |

.36 .14 .53 |

.36 .14 .54 |

Standard errors are in parentheses

_______________________________

1 Department of Political Science, Rice University Political Sciences, USA (aeh9@rice.edu).

3 Department of Political Science, Texas Christian University, USA (j.scott@tcu.edu).

3. The literature on economic sanctions also provides an important related insight to the aid conditionality foundation. Senders of sanctions – those countries who sever trade, finance, or aid relations with others in pursuit of policy goals – struggle to achieve their goals and often find that they contribute to the opposite of their intended result (e.g., Cortright and Lopez 1995; 2000; 2002; Hufbauer, Schott, Elliott and Oegg 2007; Hultman and Peksen 2017). In the area of human rights, some studies suggest that senders of sanctions may even contribute to more harmful human rights behavior by the target regime (e.g., Peksen 2009). The struggle to promote human rights via these sanctions and the unintended consequences that may result from actions to do so further suggest that donor decisions – such as democracy aid shocks – may well result in unintended outcomes that harm important donor objectives (see also Dasandi and Erez 2017). Ultimately, this suggests that sudden reductions in aid that are intended to change regime behavior may actually cause a worsening in human rights.

4. We eliminate countries scoring higher than 7 on the Polity2 composite score (-10 to 10, with 10 most democratic). We have complete data on our key variables for this time period. We focus on democracy aid to the developing world and also exclude developed countries in Asia, Western Europe and North America; the former Soviet Union and Eastern European countries; and countries that do not appear in the Polity dataset.

5. We also tested simultaneous equation models using the logged value of civil society democracy aid (to reduce the impact of outliers) and gdp-weighted civil society democracy aid for the aid process in the equation. The results were fully consistent with our models using constant 2009 dollars. We do not report the alternative results here, but they are available from the authors.

6. In Polity IV, the 21-point Polity2 variable is a composite score ranging from -10 (least democratic) to 10 (most democratic), with interregnum and transition scores (-77, -88) replaced with scores of 0 and interpolated scores respectively to reduce missing data, and interruption (-66) scores designated as missing values. Guided by Plumper and Neumayer (2010), we adjust the Polity2 variable for better face validity, retaining the Polity2 interpolation for transition scores (-88), but recoding interregnum scores (-77) with the minimum value preceding/following the interregnum to avoid artificial improvements or deteriorations of the Polity2 score from using the 0 value during the interregnum. Per Plumper and Neumayer (2010), we also recode interruptions (-66) by replacing the missing variable with Freedom House scores adjusted to the Polity2 scale, rounding to lower values. Our revised Polity2 score serves as the basis for our measure of regime conditions. We then reset the corrected scores to range from 0-20, where 0 is the most autocratic conditions and 20 the most democratic conditions.

7. For this value, we calculate log (aid value +1), which produces a range from 0-22.9 for the logged other aid variable.

8. According to Marshall (2016) " ‘Major episodes of political violence’ " involve at least 500 ‘directly-related’ fatalities and reach a level of intensity in which political violence is both systematic and sustained (a base rate of 100 ‘directly-related deaths per annum’). Episodes may be of any general type: inter-state, intra-state, or communal; they include all episodes of international, civil, ethnic, communal, and genocidal violence and warfare.

9. Because our dependent variables are scales, we also tested our models with the ordered logit technique. The results were fully consistent with the GLS models and support our argument. We do not report these tests here, but the results are available from the authors.

10. Note that we replicated all our GLS models using these other measures but include only one set of them in the appendix for efficiency. All the other results are available from the authors on request.