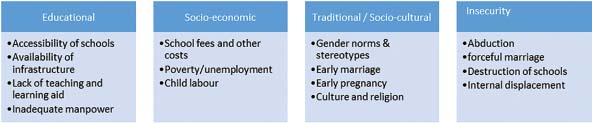

Fig. 1: Obstacles to girls’ education in northern Nigeria

Adapted and modified from British Council13

CHILD’S RIGHTS AND THE CHALLENGES OF EDUCATING THE GIRL-CHILD: ASSESSING THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF UNICEF IN NIGERIA

AGAPTUS NWOZOR1*

BLESSING OKHILLU2

Abstract: Nigeria domesticated the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child through the enactment of the Child’s Rights Act (CRA) in 2003. The CRA contains elaborate provisions on the rights to be enjoyed by the Nigerian child. In spite of this legislation, the Nigerian child, especially the girl-child, is yet to fully enjoy these rights. The major forces that militate against the rights of the girl-child are the cultural and religious norms that are intrinsically embedded in the dominant patriarchal system prevalent in Nigeria, especially in northern Nigeria. These entrenched norms contribute to the marginalization and preclusion of the girl-child from accessing education. Using the lens of radical feminism in combination with human-rights based approach, this paper interrogates the challenges faced by the girl-child in accessing education and the interventionist role played by UNICEF in salvaging the situation. The paper finds that although the interventionist program of UNICEF, that is, the Nigeria Girls’ Education Project (NGEP), contributed in re-enrolling over one million out-of-school girls back to school, a lot needs to be done to salvage the girl-child from the entrenched structural alienation that deprives her of access to education.

Keywords: Girl-child’s rights, education, radical feminism, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Nigeria.

Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION. 2. BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW. 3. THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE. 4. METHODOLOGY. 4.1. The context of the study. 4.2. Study participants. 4.3. Collection of data. 4.4. Data analysis. 5. DISCUSSION. 5.1. The context and crisis of girl-child education. 5.2. Unicef’s contributions to reversing the challenges of girl-child education. 6. CONCLUSION

1. INTRODUCTION

Nigeria passed the Child’s Rights Act (CRA) in 2003, thus domesticating and giving legal backing to both the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (Ogunniyi, 2018; Akinola, 2019; Assim, 2020). The passing of the Child’s Rights Act was a watershed in the aspirations of child’s rights campaigners in Nigeria. The Child’s Rights Act is both comprehensive and ambitious as it places the child at the epicenter of state protection. Section 1 of the Child’s Rights Act establishes the philosophical and moral compass of the rights of the child when it provides, “in every action concerning a child, whether undertaken by an individual, public or private body, institutions of service, court of law, or administrative or legislative authority, the best interest of the child shall be the primary consideration”.1 Despite the positive contributions of the Child’s Rights Act in mobilizing the legal basis for the advancement of the rights of the child, not much has changed for the Nigerian child, especially the girl-child in the area of actualizing her aspirations for quality education. As a part of the efforts to advance the fortunes of the Nigerian child, several national, non-governmental and intergovernmental organizations, including UNICEF, have initiated diverse programs.

A major challenge to actualizing the Child’s Rights Act is its lack of nationwide acceptance and implementation. Several states in northern Nigeria are opposed to several provisions of the Child’s Rights Act. Some of such provisions include the prohibition of child marriage and betrothal (sections 21 and 22), the definition of a child as anyone below the age of 18 (section 277), and the prohibition of marriage between an adopted child and members of the adoptive family (section 147), among others.2 It has been suggested that these northern states oppose the Child’s Rights Act because of the incongruence of some of its provisions with their cultural and religious norms (Ogunniyi, 2018).

Without nationwide applicability, the Child’s Rights Act, lacks the capacity to effectively improve the conditions of children (Ogunniyi, 2018; Akinola, 2019). In addition to cultural and religious forces such as child-marriage, female genital mutilation, scarification and begging (Assim, 2020), the Nigerian child faces new threats, namely, abduction, rape, drug abuse, recruitment as soldiers and dehumanization occasioned by security-induced internal displacement (Kajjo and Kaina, 2020; Ajakaiye et al., 2021). A report cited by Kajjo and Kaina indicated that between 2017 and 2019, Boko Haram recruited and used 1,385 children for direct combat and other dehumanizing roles, including being exploited as sexual slaves (Kajjo. and Kaina, 2020). In similar reports based on UNICEF sources, it was estimated that between 2013 and 2017, over 3,500 children were recruited by armed militant groups and used in the armed conflicts in northeastern Nigeria (Ajakaye, 2019).3

Globally, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has the mandate to contribute to the general wellbeing of children. The operations of UNICEF are geared towards advocating for the protection of the rights of children, helping meet their basic needs, and expanding the opportunities that will enable them to reach their full potentials.4 UNICEF has made tremendous progress in strengthening child protection systems, especially in assisting states to enact laws, and initiate policies, regulations and services across all social sectors as well as in contributing to improved protection of children from violence, exploitation and abuse. However, substantial challenges towards the full realization of the rights of children across the globe still subsist (UNICEF, 2017; UNICEF, 2019). Thus, the focus of UNICEF are all the children in the world, irrespective of where they reside or their circumstances. As an organization working to protect and assist children around the world, UNICEF is active in Nigeria and has supported the Nigerian child not only in the field of education but also in such areas as child poverty, internal displacement, child labor, and health issues (Kliesner, 2014). UNICEF has made continuous contributions to addressing the enrollment deficit in Nigeria’s educational sector, including special focus on girl-child education through its education support programs (Adedigba, 2019; Blueprint, 2020).

This paper evaluates the challenges faced by the girl-child in accessing education in the context of the Child’s Rights Act and the interventionist role played (and being played) by UNICEF in collaboration with the Nigerian government. The focus of this paper is northern Nigeria where the girl-child’s access to education has been severely constrained. Education, including the girl-child education, falls under the purview of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4, which Nigeria subscribed to in 2015. Notwithstanding the country’s commitment to pursuing SDG 4, there are still serious gaps in both the enrollment, sustenance and retention of the girl-child in basic schools (Blueprint, 2020; Federal Ministry of Education, 2020; Obiezu, 2021).

The two interrelated questions which this paper addresses are: what are the challenges faced by the girl-child in accessing education in northern Nigeria? And, how has UNICEF’s interventionist role contributed to addressing the challenge of girl-child education in northern Nigeria? Adjunct to these questions is the consideration of the prospects of institutionalizing relevant frameworks for sustainable girl-child education in northern Nigeria. This paper adopted a mixed methods approach to generate the primary and secondary data used in examining the questions under its purview. While the primary data were generated from key informants, the secondary data were obtained from relevant archival materials. The paper finds that UNICEF’s flagship program of getting out-of-school girls back to school was successful. However, the success has to be consolidated by institutionalizing relevant structures that can catalyze and sustain greater access to basic school for the girl-child. A major step towards ensuring greater enrollment and retention of the girl-child in school is the wholesale adoption of the Child’s Rights Act by all the states in Nigeria and the deployment of necessary resources for its sustained implementation.

2. BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW

In 2003, the Nigerian government enacted the Child’s Rights Act.5 This Act mainstreamed Nigeria into the circle of countries that presumably takes the protection and promotion of the rights of the child seriously. The various stakeholders championing the rights of the child in Nigeria described the enactment of the Child’s Rights Act as a milestone (Akinola, 2019:138). The Act is considered a milestone because of the long walk that characterized the process of enacting it. It took over a decade after Nigeria had ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1991 to domesticate it through the Child’s Rights Act of 2003. The decade-long period of delay was characterized by opposition by diverse groups on the grounds that certain provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child were not compliant with the cultures, traditions and other norms in the country, especially in northern states (Nzarga, 2016; AjaNwachuku, 2017; Akinola, 2019). The eventual passage of the Child’s Rights Act by Nigeria’s National Assembly in 2003 did not resolve the opposition against it. As at the end of 2020, as many as 11 out of the 36 states that make up Nigeria were yet to domesticate it (Olatunji, 2020). These states are Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Jigawa, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, Yobe, and Zamfara states. Ogunniyi (2018: 448) observes that “some states that have re-enacted the legislation have lowered certain standards, such that the statute lacks the strength to improve the conditions of children effectively”.

Prior to the enactment of the Child’s Rights Act in 2003, several subsidiary laws such as the Labour Act and the Trafficking Act existed, and contributed to the protection of the Nigerian child (AjaNwachuku, 2017; Ogunniyi, 2019). However, these laws were inadequate when juxtaposed to the provisions of the United Nations Convention of the Rights of the Child, thus necessitating a new legal framework to protect the rights of the child (AjaNwachuku, 2017: 162). Therefore, the Child’s Rights Act is the first broad and comprehensive legislation with elaborate provisions that protect the rights of the child in Nigeria (Egede, 2007; Ajanwachuku and Faga, 2018; Assim, 2020).

A major setback to the Child’s Rights Act is its non-applicability across Nigeria. As a federation, Nigeria has 36 constitutionally recognized component units called states. Since the Child’s Rights Act was passed by Nigeria’s National Assembly, only 25 states have adopted it, leaving out 11 states (Olatunji, 2020). Nigeria has a dual legal order, which allows constituent states to either agree or refuse to adopt laws, which they may have divergent perceptions. But this is only practicable if the issues at stake are within their legislative competence. In the spirit of Nigeria’s federal system, the country’s constitution provides for two legislative lists, namely the exclusive and concurrent legislative lists.6 The National Assembly exercises absolute legislative jurisdiction on items contained in the exclusive list. Both the National and State Assemblies are empowered to legislate on items in the concurrent list. However, if there is an inconsistency between the law made by the state and federal governments on an item in the concurrent list, the law made by the federal government is considered superior (Egede, 2007; Ebobrah and Eboibi, 2017). In addition, matters that are neither in the exclusive nor concurrent lists are regarded as residual and, therefore, squarely within the exclusive legislative competence of the Houses of Assembly of the States (Egede, 2007:271).

In many ways, Nigeria’s dual legal order as well as the fact that issues relating to children are in the residual list is behind the impasse surrounding the adoption of the Child’s Rights Act by the states. Although the National Assembly is empowered to enact legislations for the purpose of implementing treaties, such laws must be ratified by a majority of the legislative houses of the states in the federation before the president can assent to them (Egede, 2007). In the case of the Child’s Rights Act, the National Assembly failed to meet this constitutional requirement. Nevertheless, it went ahead to enact it into law (Ogunniyi, 2018). The lack of consensus surrounding the enactment of the Child’s Rights Act exculpates the states from any form of duty to implement it. In other words, the states are not automatically bound to implement it.

Notwithstanding the disagreement surrounding the Child’s Rights Act, its beauty is embedded in its elaborate provisions that protect and guarantee several rights to the child. These rights ensure that the child’s best interests constitute the paramount consideration of all actions of the state. It also imposes a duty on the state to give every child the overall care necessary for their wellbeing.7 One of the major aspects of the Child’s Rights Act is its emphasis on the education of the Nigerian child. Section 15, subsection 1 of the Child’s Rights Act provides, “every child has the right to free, compulsory and universal basic education and it shall be the duty of the Government in Nigeria to provide such education”.8 Although the Nigerian government has introduced a number of policies to ensure the education of Nigerian children, there are still enormous gaps in the literacy level.

Prior to the adoption of the Child’s Rights Act, the Nigerian government had introduced the Universal Basic Education (UBE) in 1999. The overall objective of the UBE is to provide free primary and secondary education to all Nigerian children between the age groups of 6 and 15 years. Despite being initiated in 1999, the UBE only took off in 2004 following the enactment of a legislative backing known as the Compulsory, Free Universal Basic Education Act of 2004 (Aja et al., 2018). The Nigerian government also introduced school feeding program in 2004 to provide a meal each school day to all primary school pupils in Nigeria. The overall tripartite objectives of the program, beyond catering for the nutritional needs of school children and thus improve their health, included the expansion of school enrolment, the enhancement of student retention, and ensuring a high completion rate (Falade et al., 2012).

The initial pilot implementation of the school feeding program under the auspices of the Federal Ministry of Education covered 12 states, namely Bauchi, Cross River, Enugu, Imo, Kano, Kebbi, Kogi, Rivers, Ogun, Osun, Nasarawa, Yobe and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). The program failed to accomplish its objective as it was stopped not long after its commencement in 10 states and the FCT leaving only Osun and Kano States, which continued with it.9 The factors identified as being responsible for undermining the program included the failure of both the supervising agency of the program, Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC), and the participating states to meet their financial obligations, inadequate policy, legal, institutional and operational framework at both the state and federal levels, and overall poor funding.10 The school feeding program was revived in 2016. The federal government announced as at May 2021 that close to ten million pupils in public schools across the country were being fed under the program (Erunke, 2021).

The northern part of Nigeria accounts for more than a disproportionate number of the 10.5 million children aged 5-14 years estimated to be out-of-school, with girl-children affected more (BBC, 2017). The net attendance rates of girl-children for primary education in states in north-eastern and north-western Nigeria are between 47.3 percent and 47.7 percent, with the implication that more than half of the girls are not in school (Premium Times, 2019).11 Several factors account for poor school enrollment in northern Nigeria: these include economic barriers, socio-cultural and religious norms and practices among others (Erulker and Bello, 2007).

UNICEF started operations in Nigeria in 1952, thereby representing one of the very first countries it established a program of cooperation on the African continent (Kliesner, 2014). According to Kliesner (2014: n.p), in those early days of UNICEF’s operations in Nigeria, its first priority was “to provide relief for Nigerians against the endemic diseases of leprosy, yaws, and malaria (the first two of which were no longer considered to be a significant public health issue by the 1960s)”. UNICEF is very active in Nigeria, and has made tremendous advances in various sectors such as child protection, education, health, nutrition, social protection, water, sanitation and hygiene (UNICEF Nigeria, 2019a). Despite the advances made by UNICEF in Nigeria, gaps are still evident. Peter Hawkins, UNICEF’s Country Representative in Nigeria, was quoted to have acknowledged, “while there have been many advances over the last years, children in Nigeria are still not accessing health, nutrition, education and other rights to the extent that they must” (UNICEF Nigeria, 2019a: n.p).

UNICEF has made enormous contributions in addressing the challenges faced by the Nigerian child, especially the girl-child, in accessing education. The current insecurity in Nigeria, which is masterminded by Boko Haram and various bandit groups, has had a destabilizing impact on children as well as their access to education. In Nigeria’s northeast geopolitical zone, insecurity has deepened humanitarian crisis. It is estimated that over 7.7 million women, men and children are affected, thus creating an acute need for help and protection for vulnerable groups (UNICEF Nigeria, 2019b). The ideological opposition of Boko Haram to western education has made schools a major target of attacks and abductions (Ajakaiye et al., 2021). Children and schools have been systematically targeted and attacked by Boko Haram and non-state armed groups, generally known as bandits, either because of their fundamental opposition to western education, or for economic gains through kidnap-for-ransom (Nwozor, 2016; Isokpan and Durojaye, 2017). The direct implication is that children, especially girls, are discouraged from going to schools with attendant mass withdrawal from schools. UNICEF recently initiated a psychosocial support program for children in northeast Nigeria with the objective being to “ensure that children are equipped to cope with and manage distress from the conflict, displacement and resulting crisis” (UNICEF Nigeria, 2019b: 9).

Since 2009 when Boko Haram entrenched its terrorist activities on the landscape of northeast Nigeria, children have been under serious threat. According to available data, an estimated three million children in northeast Nigeria require emergency education support considering that “over 2,295 teachers have been killed and 19,000 have been displaced. Almost 1,400 schools have been destroyed with the majority unable to open because of extensive damage or because they are in areas that remain unsafe”( UNICEF Nigeria, 2017a: n.p). The implication is that the northeast holds the unenviable record of being the region with the lowest literacy level, as well as the highest proportion of out-of-school children (Isokpan and Durojaye, 2017).

UNICEF has consistently evolved various programs to ensure the extension of assistance to children, especially in the area of access to education. In 2017, UNICEF together with its partners facilitated the enrollment of “nearly 750,000 children in school in the three most-affected states of northeast Nigeria” (UNICEF Nigeria, 2017b: n.p). A transit center for children was established with the support of UNICEF in Maiduguri, northeast Nigeria. The transit center caters for children formerly linked with armed groups by providing them with educational and vocational support to enable them restart their lives and put their difficult circumstances behind them (Adebayo, 2021).

UNICEF initiated Nigeria Girls’ Education Project (NGEP) with a cash transfer component to facilitate the enrolment of girl-children in schools in northern Nigeria where they are most marginalized (UNICEF Nigeria, 2017c). The overall objective of the program centered on expanding the social and economic opportunities available to girls by encouraging them to acquire education. The cash transfer component was more or less like an incentive to eliminate restrictions imposed by poverty, which is also prevalent in northern Nigeria (UNICEF Nigeria, 2017c). There is a considerable body of literature on child’s rights and girl-child education in Nigeria. The bulk of these works focused on issues relating to either child’s rights or the challenges of girl-child education in Nigeria. Thus, many of these works examined child’s rights in Nigeria vis-à-vis global expectations on child’s rights or from the perspectives of child’s rights as a component of human rights and the attendant limitations in their actualization in the country (Egede, 2007; Ibraheem, 2015; Nzarga, 2016; AjaNwachuku, 2017; Ogunniyi, 2018; Ajanwachuku and Faga, 2018; Akinola, 2019). Other strands of scholarship focused either exclusively on girl-child education or in relation to sociocultural and religious impediments to its actualization, while also dissecting the diverse nature, manifestations and implications of girl-child education to Nigeria’s national development (Eweniyi and Usman, 2013; Oluyemi and Yinusa, 2016; Ebobrah and Eboibi, 2017; Offor et al., 2021). None of the works that constitute the extant literature on child’s rights and girl-child education in Nigeria provided insights on how UNICEF’s interventionist programs have impacted, one way or another, the girl-child education within the broad context of Child’s Rights Act, hence this study.

3. THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVE

This study combined radical feminist theory with human-rights based approach to provide insights on the alienation and structural impediments to the enjoyment of rights by children, including the right to education for the girl-child. While radical feminist theory illuminates the interconnections of several forces in limiting active institutionalized intervention in driving girl-child education, the human-rights based approach provides insight into the complementary and interventionist programs of UNICEF.

Feminist theories advance assumptions about issues relating to gender, power and the very nature and boundaries of the family (Osmond and Thorne, 2009). Essentially, there is no single perspective with regards to feminism as what “counts as feminist theory is diverse and contested” (Radtke, 2017: 359). However, generally, feminism refuses to accept and, in fact, questions the notion that the inequalities between women and men are natural and inevitable (Jackson and Jones, 1998; Radtke, 2017). As such, feminism is preoccupied with four interrelated issues, namely, women and their experiences, women’s subordination and oppression under the existing social arrangement; commitment to ending the unjust subordination, and gender relations as fundamental to all social life (Jackson and Jones, 1998; Osmond and Thorne, 2009).

The radical variant of feminist theory draws attention to inequalities between men and women, which are built around subtle stratifications in the socio-economic and cultural systems within society, and which undermine and alienate women. It recognizes that gender stratification intersects with other forms of inequality to produce qualitatively different life experiences and opportunities for various groups of women and men. The major proponents of radical feminism include Andrea Dworkin, Catherine MacKinnon, Ti-Grace Atkinson, Valerie Solanas, and Alice Walker (Lorber, 1997; Chambers, 2005; Grosser and Tyler, 2021). Radical feminism anchors its theorizing on the notions of patriarchy and the politicization of women’s experiences, including their feelings (Leavy and Harris, 2019). Patriarchy advances unequal power relations that are generally exemplified and reinforced by the distribution of functions within the society. The entrenchment of this unequal relations between men and women shapes societal perceptions and reinforces the internalization of subordination-superordination divide (Lorber, 1997; Qin, 2004).

The patriarchal system in northern Nigeria is strengthened by the embedded influence of cultural and religious norms. The patriarchal system in northern Nigeria tends to favor practices that oppress, subjugate and exploit women. It also disfavors initiatives that could be antithetical to the patriarchal status quo. Thus, the patriarchal structures in northern Nigeria restrict girl-children as well as their educational opportunities, especially through such religious and cultural practices as child betrothal and early marriage. Such restrictions rob girl-children of access to education while at the same time help to maintain male domination.

Human rights-based approach to education focuses on the educational empowerment of the child. Its overarching goal is essentially to ensure that each child receives a quality education that values and promotes their right to dignity and optimum growth. As Muñoz has asserted, “a rights-based approach to Education for All is a holistic one, encompassing access to education, educational quality (based on human rights values and principles) and the environment in which education is provided” (Muñoz, 2007: ix). Developing an educational approach based on human rights requires a framework that addresses the right of access to education, the right to quality education and respect for human rights in education. The right to education includes a commitment to guarantee equal access, including taking all steps possible to meet the needs of the most vulnerable children.

A rights-based approach to education rests on the redefinition and adaptation of the human rights principles of nondiscrimination, equality, accountability, transparency, participation, and empowerment into the education sector. This introduces a root cause approach that focuses primarily on matters of state policy and discrimination (Uvin, 2007). Human rights-based approach underscores the right to education of all and sundry, especially as basis to address other threats to the enjoyment of human rights, including poverty, and underdevelopment. In this context, human rights-based approach to education guides and organizes all aspects of learning, from policy to the classroom. In other words, the society, including the parents, teachers, state, and other stakeholders are not expected to see this right as charity but a duty and are bound to meet their obligations and support children (as rights holders to claim their rights) (Uvin, 2007; Broberg and Sano, 2018). It is in this regard that the UNICEF has evolved various programs to remedy the education-deficit of the girl-child in Nigeria and ensure that they can access education despite the patriarchal challenges.

4. METHODOLOGY

As a state party to both the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, the expectation was that Nigeria would have completely domesticated the provisions of these international instruments by now. However, this is not the case. The domestication effort is haphazard, with a large segment of the country yet to enact the necessary sub-regional laws to give force to child’s rights. The focus of this paper is the girl-child education, which is intertwined with other rights guaranteed the child by the Child’s Rights Act, and the contributions of UNICEF for its realization. The paper adopted the mixed methods approach of qualitative research in which both primary and secondary data were generated to address the key concerns of the study.

4.1. The context of the study

The focus of this study is Nigeria. Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and among the top ten most populous countries in the world. The estimated population of Nigeria in 2020 was 206.14 million with the composition of male and female being 50.68 percent or 104.47 million and 49.32 percent or 101.67 million respectively.12 Nigeria is federation of 36 states. Out of these 36 states, 19 states and the federal capital territory (FCT) are in the north while the remaining 17 states are located in the south. Islam and Christianity are predominant religions in northern and southern Nigeria respectively, with pockets of adherents of African traditional religions on both divides of the geo-polities. Nigeria operates pluralist legal system: the north and south operate different legal codes. While the north operates the penal code, which is based mainly on Sharia law (Braimah, 2014), the south operates the criminal code (Bello, 2013; Ekhator, 2015).

This study focused on northern Nigeria where the adoption of child’s rights as encapsulated in the Child’s Rights Act has been contentious. As already noted, 11 northern states are yet to domesticate the Child’s Rights Act. The basis for their reluctance to adopt the law is its substantial non-adherence to subsisting penal codes and cultural norms in northern Nigeria. The implication is that most northern states, including those yet to implement the Child’s Rights Act, have weak frameworks to implement child’s rights. The girl-child education constitutes a major challenge due to the extant religio-cultural practices in the north, especially child marriage and betrothal as well as poverty that tend to militate against it (UNICEF Nigeria, 2017c; Assim, 2020). It is on the basis of the foregoing that UNICEF’s programs on education focus on girl-child education in the north. Girl-child education in southern Nigeria is not an issue as cultural norms have been shaped by religion and criminal codes. Thus, the preoccupations of UNICEF in the south center on other aspects of its mandate.

4.2. Study participants

This paper generated its primary data from in-depth interviews involving 31 key informants. The key informants were chosen through purposive sampling technique. Purposive sampling technique represents an intentional selection of informants based on certain criteria (Palinkas et al., 2015). For this paper, the key informants were selected on the bases of knowledgeability and availability for interviews. Thus, the decision rule for including persons as key informants for this study centered principally on the possession of demonstrable expertise and knowledge as well as appropriate affiliation to relevant institutions.

The key informants comprised: representatives from Nigeria’s Ministry of Education (KI-1-4), Ministry of Women Affairs (KI-5-7), UNICEF Nigeria (KI-8-12), Ministry of Justice (KI-13-15), representative girl-children KI-16-20, academics/researchers in the universities (KI-21-24), civil society organizations (KI-25-29), and public and social affairs analysts (KI-30-31). The key informants participated voluntarily in the interviews and were aware that they could withdraw whenever they pleased, without a need for them to justify their decision.

4.3. Collection of data

This paper made use of both primary and secondary data. The primary data were generated from the 31 key informants already mentioned. The instrument used to collect the data was an interview guide that contained semi-structured set of questions. Semi-structured interview format facilitates effective communication between the researcher and the respondents as it creates a good platform for follow-up questions and conversations beyond prepared questions (Nwozor et al., 2021; Passley, 2021). A combination of face-to-face interviews, phone discussions, and e-mail exchanges were adopted to elicit and crosscheck information from the key informants. The use of semi-structured interview guide provided the researchers and key informants the opportunity to exhaust all the angles and perspectives of the answers. The secondary data for this paper were sourced from archival materials, including the official webpages of UNICEF, journal articles, and government documents.

4.4. Data analysis

The data were reviewed, validated and processed. Thematic content analysis was used to analyze the data. Thematic content analysis is a method used to analyze documents and texts in order to identify, sift and interpret patterns of meaning across data (Nowell et al., 2017). Thus, with the aid of thematic content analysis, insights and responses from the key informants were harnessed and synthesized into categories and themes. This technique provided the basis for the establishment of trends and patterns in the words used, their frequencies, their relationships, and the structures and discourses of communication (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). The key informants were represented with codes to ensure their anonymity. In the same vein, the secondary data from archival materials were systematically examined for the purpose of extracting and establishing patterns of meanings, and developing relevant empirical insights necessary to illuminate the major problems being examined. All the data were also analyzed and relevant conclusions drawn based on inductive method of interpretation. As part of the strategies to ensure the credibility and trustworthiness of the coding and interpretation of the data, the paper was subjected to member checking by a few of the key informants and the authors (Birt et al., 2016). According to Brear (2019: 944), member checking is “the process of providing research participants with opportunities to check the accuracy of, expand, amend and/or comment on, raw data or research results”. This strategy made it possible to ensure and establish the transactional validity of the study.

5. DISCUSSION

The paper focused on the broad question of girl-child marginalization in accessing education and the contributions made by UNICEF towards addressing this marginalization in northern Nigeria. The key informants chosen for this study were broadly interviewed on the extent of their awareness and knowledge about the challenges connected to the implementation of the components of the Child’s Rights Act that relate to education. In addition, they were interviewed on the alienation and marginalization of the girl-child in accessing education in Nigeria as well as the effectiveness of the interventionist role played by UNICEF in ensuring greater enrolment of out-of-school children, especially girl-children, into schools. The analysis of responses from the key informants identified and validated major themes that revolved around the nature of the marginalization of the girl-child in accessing education, its overall implications on national development, and the contributions of the interventionist programs of UNICEF in expanding access to basic education for girl-children.

5.1. The context and crisis of girl-child education

As already mentioned, Nigeria has an extant legislation that domesticated the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. This legislation, the Child’s Rights Act, has been in operation since 2003. The unanimous views of our key informants indicated that the Child’s Rights Act, as a piece of legislative protection for the Nigerian child, is not adequately complemented with political protection to ensure the full enjoyment of the rights contained therein. Fig. 1 below shows the several obstacles to girl education in northern Nigeria. In a further elaboration of the disconnect between the provisions of the Child’s Rights Act and the rights actually enjoyed by the child, KI-8 contended,

the lot of the Nigerian child is far from the type and quality of life envisaged by the Child’s Rights Act as exemplified by the persistence of several practices ranging from poor access to education to lack of adequate protection from such exploitative practices as early child betrothal and marriage, child labor, and female genital mutilation among others.

Fig. 1: Obstacles to girls’ education in northern Nigeria

Adapted and modified from British Council13

A corollary to the limited acceptance of the Child’s Rights Act in northern Nigeria is the absence of sustained advocacy program at the grassroots. KI-11 commented that “we at UNICEF Nigeria are trying to reach out to the masses, especially the parents but there is a limit to which we can go without a robust support base at the state-level”. KI_16 observed,

it seems to me that our parents have not been fully made to understand why they should make the sacrifice of sending us, their daughters, to school instead of marrying us off. I know the tradition is quite strong in this regard and against the girls. But I believe that more discussions can open more doors of cooperation on this issue of girl-child education.

The strong tradition alluded to by KI-16 is the iron-cast patriarchal system that is reinforced and energized by culture and religion. KI-25 argued,

there is class character in this whole issue of child rights generally and girl-child rights particularly. What I see is an established pattern of girl-children being marginalized and denied access to education among poor households. Thus, beyond the influence of the prevalent patriarchal system, there are other forces that shape the access of girl children to education. There is poverty, there is this perception of girl-children as sources of wealth, there is this haste, if you like, impatience by parents to free themselves from the responsibility of catering for their children, and above all, there is general poor understanding of the relevance of education among the lower class.

Thus, in northern Nigeria, the girl-child is under unremitting threats as she faces serious challenges encapsulated in such practices as early marriage, female genital mutilation and alms begging (Ogunniyi, 2018; Assim, 2020). KI-5 argued that “the non-adoption of the Child’s Rights Act provides a cover for the continued marginalization and exploitation of the child, especially the girl-child in the north. Of course, if there is no law, there will be no infringement and therefore no punishment”. This view was put in perspective by KI-17 thus, “we [as girls being marginalized] have no one to report to or appeal to for assistance about our desire to go to school. It is the same in cases where some of the girls stopped school for various reasons… there is just no one to help out.” One of the key informants, KI-30 observed,

the non-adoption of the Child’s Rights Act by some northern states has other consequences. Even if non-governmental or intergovernmental organizations like UINCEF want to help, they are constrained as they may not be able to fund access to education without some kind of counterpart funding.

KI-13 provided more insights and elaboration:

these states that have not legitimized the Child’s Rights Act cannot budget for the enforcement of those provisions that might have specific funding requirements. This has a limiting effect on pro-rights groups in terms of compelling these states to establish the necessary institutional framework to enforce the enjoyment of such rights by children in such states.

As important as the Child’s Rights Act might be, its non-adoption ought not to acquit the states that are yet to adopt it from the responsibility of protecting and promoting the human rights of children in their domains. This is because there are other subsidiary legislations (such as the Labour Act and the Trafficking Act), with provisions that address child-related issues and which could therefore serve the legal purpose of protecting children (Ajanwachuku, 2017; Ogunniyi, 2018). However, these adjunct legislations do not strictly focus on the rights of children to education. KI-16 asserted that “the failure of the government at all levels in northern Nigeria to pursue a deliberate redemptive policy for the children is responsible for the educational crisis that encompasses the child in that region”. The education profile of children, especially girl-children in northern Nigeria, is precarious, which is an indication of lack of commitment on the part of the government to holistically address the education deficits of children. Nigeria has the highest number of out-of-school children in sub-Saharan Africa, which is estimated at one in every five of out-of-school children in the world (Premium Times, 2021).

Underscoring how advocacy gap has sustained the marginalization of the girl-child, KI-29 expressed the view, “in the absence of sustained campaign for degenderizing educational benefits, the mindset of average parents in the north is that they are not doing any wrong by not sending their girl-children to school. This makes the discussion a bit more complex”. The foregoing view resonated in the response of KI-20 that “our parents keep assuring us that our not going to school and staying at home to help the family in the farms and markets is also a way of contributing to our economic wellbeing”. The views of the key informants referred to above provide insights on the connections between socio-economic constraints and the low educational enrolment of the girl-child. National statistical evidence indicates nationwide prevalence of poverty and its particular intensity in northern Nigeria. Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics estimated that 40.09 percent or 82.9 million Nigerians were living below the country’s poverty line of N137,430 (US$381.75 at N360/$1) per annum as at 2019.14 Regional disaggregation of the prevalence of poverty pointed to northern Nigeria as having a disproportionate percentage of people living in poverty.

With regard to the impact of poverty on the prospects of girl child education, KI-4 averred, “in the face of poverty and the imperative of survival, education is disincentivized while child marriage is incentivized as a means of lessening the economic burden on disadvantaged households”. In line with the foregoing contention about the influence of poverty as a push factor in child-marriage, KI-22 noted that “poverty has had negative cyclical and reinforcing impacts on the prospects of girl-children having a brighter future, as it robs them of education and thus spawns a new cycle of poverty”. The leveraging of child marriage as a survivalist tool by households in northern Nigeria has been noted in literature. In this regard, child marriages have been used to further the economic interests of households, build new and reinforce existing social ties, and improve or enhance social statuses (Yaya et al., 2019; Obaje et al., 2020). The entrenched practice of child marriage and attendant benefits undermine the appeal of girl-education. It is even made more complex by the politicization of the Child’s Rights Act.

5.2. UNICEF’s contributions to reversing the challenges of girl-child education

UNICEF has made significant contributions in its area of mandate, which is the advancement of the interest of children in all ramifications. UNICEF’s commitment in Nigeria, as in other parts of the world, is to contribute to the full realization of the rights of all children by helping them to build a strong foundation that will pave the way for them to fulfil their potentials. UNICEF in Nigeria makes its contributions as partners to the government and, where possible, supports the government in its policy, decision-making, social budgeting, planning and program processes that focus on children’s rights.15 Thus, the range of operations that UNICEF engages in traverses education, healthcare, including mandatory immunization, nutrition and child protection.

Majority of the key informants opined that the various levels of governments in northern Nigeria are not doing as much as they should to encourage girl-child education. KI-2 acknowledged that “the estimates of out-of-school children in the north, especially girl-children are indications that enough is not being done to educate the people”. KI-15 linked the interventionist role of UNICEF to the failure of the states to advance the rights of children and asserted, “it was the suboptimal attention to girl-child education by various levels of government in northern Nigeria that catalyzed UNICEF’s girls’ education project, which is aimed at salvaging the exclusion of girl-children from obtaining education”. This view aligns with the call by Mohamed Fall, the then UNICEF Representative in Nigeria, on Nigerian government and other stakeholders during the 2018 International World Children’s Day to “invest in long-lasting institutional and community-based systems and policies for children’s survival, growth and development” (UNICEF, 2018).

UNICEF has evolved and implemented a plethora of programs aimed at assisting and uplifting Nigerian children in diverse areas. Its programs are designed to provide all children an equitable and fair chance to survive and fulfil their dreams, whatever they might be (UNICEF, 2018). The dismal figures about enrolment and retention at the basic school levels, led to the intervention of UNICEF through several programs. Children play a significant role in any country's national development considering that they constitute the succeeding generations that will continue to drive policies designed to take the country to the next level (UNICEF, 2017). UNICEF programs on education tend to prioritize and target children that are most unlikely to access education. The singular overall objective of UNICEF programs is to serve as mechanisms to empower children to acquire skills and knowledge for lifelong learning.16

The Nigeria Girls' Education Project (NGEP) was initiated by UNICEF and funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID). The project was developed in 2012 to tackle the high-burden of out-of-school girls, which was, and still is, prevalent in northern Nigeria (Federal Ministry of Education, 2020). Thus, the focus of the project was to increase the enrolment of girls in schools for basic education (UNICEF Nigeria, 2017c). The pro-argument for girl-child education is often based on the logic of its impact on development. KI-2 emphasized it thus, “the girl-child education charts the course for enduring development in countries. For a country like Nigeria where poverty is pervasive, educating women offers hope of reversing it”. This view has been echoed by development institutions. The World Bank and UNICEF have always contended that the education of girl-children has positive multiplier effects that ensure improved family life, high productivity and increased earning capacity, which combine to uplift the quality of life among households, communities, and countries.17

The Girls’ Education Project ran for eight years between 2012 and 2020 and covered six northern states, namely Bauchi, Kano, Katsina, Niger, Sokoto, and Zamfara states. The unconditional cash transfer program, an important component of the project, facilitated the positive results recorded by the project. The cash transfer program contributed in changing community and family dynamics by reducing the financial barriers to girls’ enrolment and attendance at school (UNICEF Nigeria, 2017c). The key informants agreed that the cash transfer program was the winning strategy of the Nigeria Girls' Education Project that facilitated landmark enrolment of girl-children into schools. KI-9 noted that the cash transfer program played the role of “removing the burden of sponsorship from parents and transferring same to UNICEF and their partners”. KI- 30 held the view that the

[cash transfer program] was the elixir that stimulated the effective mobilization of girl-children back to basic school, convinced their parents to allow them to go back, sustained their school attendance, and provided hope and concrete assurance to the girls for a better tomorrow.

Different perspectives emerged from the key informants with regard to the question, “has UNICEF done enough to effectively address the gaps in girl-child education?” KI-11 provided the following insights,

Within the context of the resources available, UNICEF has done very well. Don’t forget that UNICEF’s funding comes from stakeholders. As you might have known, the funding streams are not enough to tackle this huge problem of girl-child education. But it did record significant achievements in narrowing the gap of out-of-school girls.

Bringing the challenges of mobilizing the girls for school enrolment and retention to the fore, KI-8 averred,

The mindset of people in the six northern states where UNICEF operated is something of curious interest. There was this sense of entitlement resulting in threats by some parents that they would withdraw their daughters from schools. They didn’t seem to understand that ultimately, the training of their girls would translate into economic gains for them. In a way some of these parents saw the gain of the program in the immediate, and as some kind of poverty alleviation program.

The Nigeria Girls’ Education Project was envisaged to achieve results that would advance girls’ education in northern Nigeria. Thus, the expected areas of impact of the NGEP included the improvement of enrolment and retention of girls in basic education, and the strengthening of the capacity of teachers to deliver effective teaching (Federal Ministry of Education, 2020; UNICEF Nigeria, 2017c).

The Nigeria Girls' Education Project was described by UNICEF’s Chief of Education, Euphrates Wose, as a “huge success”.18 UNICEF identified the expansion in the enrolment profile of girl-children, the increased awareness on the importance of education, and positive disposition of parents to the education of girl-children as the indicators of the success of the Nigeria Girls' Education Project.19 The key informants were asked about their impression of the success or otherwise of the program. KI-19 observed that “success is limited because not all the girls that wanted to go to school got the opportunity to participate”. To KI-25,

the major setback to the program was that UNICEF operated within strict budgetary windows, which made it difficult to explore far afield to cover all the grounds and enroll as many interested girls as possible.

While acknowledging that the program was a success, KI-31 raised some fundamental issues:

Within the context of what UNICEF set out to do, it is fair to give the organization a high mark. However, my problem is that there is no known modalities for selecting the girls that were enrolled into schools. This poses a challenge. I am not suggesting nepotism, no, not at all. My worry is if there is no established mechanism for choosing the girls, how will an objective evaluation of the program be feasible, and how can future programs in this regard be modelled and pursued to ensure continuity?

Beyond the immediate success of the program, KI-27 raised the issue of sustainability: “there is no enduring framework to continue with the enrollment of girls into schools. The UNICEF appeared to have used a hotchpotch of ad hoc mechanisms for its advocacy and enrollment exercises”. KI-22 also posited,

the uncertainty about funding may have a serious setback on the quest for sustained enrollment of girl-children into schools. There might even be a reversal in the success that we are celebrating today. Thus, the key question is how will the funds keep flowing to ensure the sustainability of girl-child education?

The foregoing issues raised by the key informants in connection with the sustainability of the girl-child education are quite legitimate. Through the Nigeria Girls' Education Project, UNICEF succeeded in mobilizing a total of 1,135, 465 out-of-school children, mainly girls back to basic school levels (Blueprint, 2020). The number was from the estimated total of 3,530,035 out-of-school children (Federal Ministry of Education, 2020). Why the future of the girl-child education matters is the funding constraints of UNICEF and the non-committal of the northern states to this project. According to UNICEF sources, only Sokoto state made budgetary provisions to sustain the girl-child education initiative.20 What this implies is that sustaining the success recorded by UNICEF through the Nigeria Girls' Education Project in the face of uncertain funding constitutes the immediate challenge to girl-child education in northern Nigeria.

6. CONCLUSION

The Nigerian girl-child faces several challenges that are rooted in cultural and religious norms and reinforced by the patriarchal system. The Child’s Rights Act represents a quintessential codification of child’s rights in Nigeria. However, the law does not enjoy nationwide acceptance as some 11 states are yet to adopt it due to their opposition to its many provisions (Ogunniyi, 2018). The result is that there is no specific nationwide standard of rights accorded the Nigerian child. The major aspect of the child’s rights that requires urgent state intervention is access to education as it is intertwined with other rights. The current estimates of out-of-school children in Nigeria are about 10.5 million, with a majority of these children being girls (BBC, 2017). Yet, primary education is officially free and compulsory. The relevance of education in driving national development and combating poverty has been emphasized.21 While, it is estimated that Nigeria loses US$7.6 billion annually for not educating its girl-child (Obaje et al., 2019), it has equally been established that education will protect the girl-child from early marriage and position her for greater productivity. According to Feser, more than 80 percent of girls with no education marry before 18 years and if a girl finishes primary school, the likelihood of getting married before age 18 drops significantly (Feser, 2017).

UNICEF’s Nigeria Girls' Education Project greatly assisted in re-enrolling out-of-school girls back to school. As at the end of 2020 when the program was concluded in the six northern states of Bauchi, Kano, Katsina, Niger, Sokoto, and Zamfara, about 1,135, 465 out-of-school children, mainly girls had been re-mobilized to basic school. The success of UNICEF’s Nigeria Girls' Education Project represents a tremendous achievement and signposts the likelihood of reversing the marginalization and alienation of the child-girl from accessing education.

Notwithstanding the success of UNICEF’s interventionist roles through the Nigeria Girls' Education Project, girl-child education still faces real challenges that could overturn the progress recorded. Thus, this paper recommends:

i)The intensification of discussions to get the 11 northern states that are yet to domesticate the Child’s Rights Act to do so. Additionally, stakeholders in the child’s rights project should engage the northern states that have domesticated the law to ensure its implementation;

ii)Sustainable incentives should be evolved to ensure the retention of students in schools. This will involve sustained advocacy and awareness-creation campaigns.

iii)The relevant national and international stakeholders should be mobilized to ensure a steady flow of funds. Funding is particularly important considering that the success of UNICEF’s Nigeria Girls' Education Project was partly due to the positive impact of the unconditional cash transfer program associated with it. State governments in northern Nigeria may also need to incorporate the girl-child education within the ambit of their poverty alleviation programs.

REFERENCES

ADEDIGBA, A. (2019) ‘UNICEF to assist with enrolment of one million Nigerian girls in schools’, Premium Times, 28 August. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/more-news/349104-unicef-to-assist-with-enrolment-of-one-million-nigerian-girls-in-schools.html

AJA, S. N., EGWU, S. O., AJA-OKORIE, U., ANI, T. AND AMUTA, N. C. (2018) ‘Universal basic education (UBE) policy implementation challenges: the dilemma of junior secondary schools administrators in Nigeria’, International Journal of Educational Administration and Policy Studies, 10(7), pp. 83-90. doi:10.5897/IJEAPS2017.0511

AJAKAIYE, O. O. P., NWOZOR, A., OJEKA, J. D., ALEYOMI, M. B., OWOEYE, O., OJEKA-JOHN, R. AND OKIDU, O. (2021). ‘Media, terrorism reporting and lessons in awareness sustenance: the Nigerian newspapers’ coverage of the Chibok girls’ abduction’, Brazilian Journalism Research, 17(1), pp. 118-151. doi:10.25200/BJR.v17n1.2021.1329

AJAKAYE, R. O. (2019) ‘3,500 child soldiers recruited in Nigeria: UNICEF’, 4 December. Available at: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/africa/3-500-child-soldiers-recruited-in-nigeria-unicef/1450584

AJANWACHUKU, M. A. (2017) ‘The Nigerian child and the right to participation: a peep through the window of “the best interest” clause of the child’s rights act’, Beijing Law Review, 8, pp. 159-170. doi:10.4236/blr.2017.82009

AJANWACHUKU, M. A. AND FAGA, H. P. (2018) ‘The Nigerian child’s rights act and rights of children with disabilities: what hope for enforcement?’ Curentul Juridic – Juridical Current, 72(1), pp. 57-66

AKINOLA, O. (2019) ‘Who is a child? The politics of human rights, the Convention on the Right of the Child (CRC), and child marriage in Nigeria’, in Blouin-Genest, G., Doran, M. and Paquerot, S. (eds.) Human rights as battlefields: changing practices and contestations. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, pp.129–148.

ASSIM, U. M. (2020) ‘Why the Child’s Rights Act still doesn’t apply throughout Nigeria’, The Conversation, 24 September. Available at: https://theconversation.com/why-the-childs-rights-act-still-doesnt-apply-throughout-nigeria-145345

BBC (2017) ‘Nigeria has ‘largest number of children out-of-school’ in the world’, 25 July. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-40715305

BELLO, A. O. (2013) ‘Criminal law in Nigeria in the last 53 years: Trends and prospects for the future’, Acta Universitatis Danubius Juridica, 9(1), pp. 15-37

BIRT, L., SCOTT, S., CAVERS, D., CAMPBELL, C. and WALTER, F. (2016) ‘Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation?’ Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), pp. 1802–1811. doi:10.1177/1049732316654870

BLUEPRINT (2020) ‘UNICEF enrols over 1.2m out-of-school girls in Nigeria’, 14 November. Available at: https://www.blueprint.ng/unicef-enrols-over-1-2m-out-of-school-girls-in-nigeria/

BRAIMAH, T. S. (2014) ‘Child marriage in northern Nigeria: Section 61 of part I of the 1999 Constitution and the protection of children against child marriage’, African Human Rights Law Journal, 14, pp. 474-488.

BREAR, M. (2019) ‘Process and outcomes of a recursive, dialogic member checking approach: a project ethnography’, Qualitative Health Research, 29(7), pp. 944-957. doi:10.1177/1049732318812448

BRITISH COUNCIL (2014) ‘Girls’ education in Nigeria: Report 2014 issues, influencers and actions’. Available at: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/british-council-girls-education-nigeria-report.pdf

BROBERG, M. and SANO, H. (2018) ‘Strengths and weaknesses in a human rights-based approach to international development: an analysis of a rights-based approach to development assistance based on practical experiences’, The International Journal of Human Rights, 22(5), pp. 664-680. doi:10.1080/13642987.2017.1408591

CHAMBERS, C. (2005) ‘Masculine domination, radical feminism and change’, Feminist Theory, 6(3), pp. 325–346. doi:10.1177/1464700105057367

CHILD’S RIGHT ACT, 2003, Cap C50 Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 2010. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5568201f4.pdf

CONSTITUTION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA (1999) (AS AMENDED). Lagos: Government Printers

EBOBRAH, S. AND EBOIBI, F. (2017) ‘Federalism and the challenge of applying international human rights law against child marriage in Africa’, Journal of African Law, 61(03), pp. 333–354. doi:10.1017/s0021855317000195

EGEDE, E. (2007) ‘Bringing human rights home: An examination of the domestication of human rights treaties in Nigeria’, Journal of African Law, 51(02), pp. 249-284. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021855307000290

EKHATOR, E. O. (2015) ‘Women and the law in Nigeria: a reappraisal. Journal of International Women's Studies, 16(2), pp. 285-296.

ERULKER, A. S. AND BELLO, M. (2007) ‘The experience of married adolescent girls in northern Nigeria’. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/ForcedMarriage/NGO/PopulationCouncil24.pdf

ERUNKE, J. (2021) ‘NHGSFP: We’re feeding 10m pupils in schools, says FG’, Vanguard, 25 May. Available at: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2021/05/nhgsfp-were-feeding-10m-pupils-in-schools-says-fg/

EWENIYI, G. B. AND USMAN, I. G. (2013) ‘Perception of parents on the socio-cultural, religious and economic factors affecting girl-child education in the northern parts of Nigeria’, African Research Review, 7(3), pp. 58-74.

FALADE, O. S., OTEMUYIWA, I., OLUWASOLA, O., OLADIPO, W. AND ADEWUSI, S. A. (2012) ‘School feeding programme in Nigeria: the nutritional status of pupils in a public primary school in Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria’, Food and Nutrition Sciences, 3, pp. 596-605. doi:10.4236/fns.2012.35082.

FEDERAL MINISTRY OF EDUCATION (2020) ‘Final evaluation of the girls education programme 2012-2020 in northern Nigeria’. Available at: https://www.ungm.org/UNUser/Documents/DownloadPublicDocument?docId=1004733

FESER, M. (2017) ‘5 countries with highest numbers of child marriage’, Global Citizen, 6 July. Available at: https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/5-countries-with-highest-child-marriage/?template=next

GROSSER, K. AND TYLER, M. (2021) ‘Sexual harassment, sexual violence and CSR: radical feminist theory and a human rights perspective’, Journal of Business Ethics, (in press). doi:10.1007/s10551-020-04724-w.

IBRAHEEM, T. (2015) ‘Legal framework for the protection of child rights in Nigeria’, Agora International Journal of Juridical Sciences, 9(3), pp. 46-52. doi:10.15837/aijjs.v9i3.2117

ISOKPAN, A. J. AND DUROJAYE, E. (2017) ‘Impact of the Boko Haram Insurgency on the child’s right to education in Nigeria’, Potchefstroom Electronic Law Journal, 19(1), pp. 1–43. doi:10.17159/1727-3781/2016/v19i0a1299

JACKSON, S. AND JONES, J. (1998) ‘Thinking for ourselves: an introduction to feminist theorizing’, in S. Jackson & J. Jones (Eds.), Contemporary feminist theories. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 1-11.

KAJJO, S. AND KAINA, H. M. (2020) ‘Experts: Boko Haram recruiting children as soldiers, suicide bombers’, VOA News, 4 September. Available at: https://www.voanews.com/a/extremism-watch_experts-boko-haram-recruiting-children-soldiers-suicide-bombers/6195472.html

KLIESNER, K. W. (2014) ‘UNICEF 60 years after its establishment in Nigeria’, Borgen Magazine, 10 February. https://www.borgenmagazine.com/unicef-60-years-establishment-nigeria/

LEAVY, P. AND HARRIS, A. (2019) Contemporary feminist research from theory to practice. New York: The Guilford Press.

LORBER, J. (1997) ‘The variety of feminisms and their contributions to gender equality’, Oldenburger Universitätsreden Nr. 97. Available at: http://oops.uni-oldenburg.de/1269/1/ur97.pdf

MUÑOZ, V. (2007) ‘Foreword’, in A human rights-based approach to education for all. New York/ Paris: United Nations Children’s Fund/ United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

NEWS AGENCY OF NIGERIA (2019) ‘UNICEF says girls education project a huge success’, 21 September. Available at: https://www.pulse.ng/communities/student/unicef-says-girls-education-project-a-huge-success/hvt4lhr

NEXTIER SPD (2021) ‘Children in conflict zones’, 29 July. Available at: https://nextierspd.com/children-in-conflict-zones/

NIGERIA HOME GROWN SCHOOL FEEDING STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2020 CONFERENCE READY VERSION (n.d). Available at: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/nig169078.pdf

NOWELL, L. S., NORRIS, J. M., WHITE, D. E. AND MOULES, N. J. (2017) ‘Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1-13. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847

NWOZOR, A. (2016) ‘Democracy and terrorism: the Boko Haram insurgency in Nigeria’, in Omotoso, F. and Kehinde, M. (eds.) Democratic governance and political participation in Nigeria, 1999-2014. Denver, CO: Spears Media Press, pp. 313-340.

NWOZOR, A., OSHEWOLO, S., OWOEYE, G. AND OKIDU, O. (2021) ‘Nigeria's quest for alternative clean energy development: a cobweb of opportunities, pitfalls and multiple dilemmas’, Energy Policy, 149, 112070. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2020.112070

NZARGA, F. D. (2016) ‘Impediments to the domestication of Nigeria Child Rights Act by the states’, Research on Humanities and Social Sciences, 6(9), pp. 123-130.

OBAJE, H. I., OKENGWU, C. G., UWIMANA, A., SEBINEZA, H. K. AND OKORIE, C. E. (2020) ‘Ending child marriage in Nigeria: The maternal and child health country-wide policy’, Journal of Science Policy & Governance, 17(1), pp. 1-6. doi:0.38126/JSPG170116

OBIEZU, T. (2021) ‘Officials say more 3 million children are out of school in Nigeria’, VOA News, 22 March. Available at: https://www.voanews.com/a/africa_officials-say-3-million-more-children-are-out-school-nigeria/6203611.html

OFFOR, U. I., ANADI, C. C., NWARU, P. E. AND OFFIAH, C. (2021) ‘Issues in girl-child education in Nigeria: implications for sustainable development’, Unizik Journal of Educational Research and Policy Studies, 4, pp. 227-242.

OGUNNIYI, D. (2018) ‘The challenge of domesticating children’s rights treaties in Nigeria and alternative legal avenues for protecting children’, Journal of African Law, 62(3), pp. 447–470. doi:10.1017/s0021855318000232

OGUNNIYI, D. (2019) ‘There are still huge gaps in Nigeria’s efforts to protect children’, The Conversation, 24 November. Available at: https://theconversation.com/there-are-still-huge-gaps-in-nigerias-efforts-to-protect-children-127031

OLATUNJI, H. (2020) ‘11 states yet to domesticate Child Rights Act — 17 years after passage’, The Cable, 14 October. Available at: https://www.thecable.ng/11-states-yet-to-domesticate-child-rights-act-17-years-after-passage

OLUYEMI, J. A. AND YINUSA, M. A. (2016) ‘Girl-child education in Nigeria: issues and implications on national development’, Zimbabwe Journal of Educational Research, 28(1), pp. 44-60.

OSMOND, M. W. AND THORNE, B. (2009) ‘Feminist theories’, in Boss, P., Doherty, W. J., LaRossa, R., Schumm, W. R. and Steinmetz, S. K. (eds.) Sourcebook of family theories and methods. Boston, MA: Springer, pp. 591-625. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-85764-0_23

PALINKAS, L. A., HORWITZ, S. M., GREEN, C. A., WISDOM, J. P., DUAN, N. AND HOAGWOOD, K. (2015) ‘Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research’, Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), pp. 533–544. doi:10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y.

PASSLEY, C. E. (2021) ‘Preparing undergraduate and graduate students for semi-structured interview sessions with academic library staff post-flood disaster’, The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 47(3), 102332. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2021.102332.

PREMIUM TIMES (2019) ‘39% of children in North-west, except Kaduna, are out of school – UNICEF’, 27 August. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/regional/nwest/348897-39-of-children-in-north-west-except-kaduna-are-out-of-school-unicef.html

PREMIUM TIMES (2021) ‘Nigeria has highest number of out-of-school children in sub-Sahara Africa – Minister’, 29 June. Available at: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/headlines/470545-nigeria-has-highest-number-of-out-of-school-children-in-sub-sahara-africa-minister.html

QIN, D. (2004) ‘Toward a critical feminist perspective of culture and self’, Feminism & Psychology, 14(2), pp. 297-312. doi:10.1177/0959-353504042183.

RADTKE, H. L. (2017) ‘Feminist theory in Feminism &Psychology [Part I]: dealing with differences and negotiating the biological’, Feminism & Psychology, 27(3), pp. 357–377.

UNICEF (2017) ‘For every child, results’. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/media/49591/file/UNICEF_For_Every_Child_Results_May_2017_ENG.pdf

UNICEF (2018) ‘UNICEF calls for leaders to re-commit to child survival and development on International World Children’s Day’, Press release, 20 November. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/unicef-calls-leaders-re-commit-child-survival-and-development-international-world

UNICEF. (2019) For every child, every right: The Convention on the Rights of the Child at a crossroads. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

UNICEF NIGERIA (2007) ‘Girls’ education’, Information Sheet, September. Available at: https://nairametrics.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Fact-sheets-on-Girls-Education.pdf

UNICEF NIGERIA (2017a) ‘More than half of all schools remain closed in Borno state, epicentre of the Boko Haram crisis in northeast Nigeria’, Press Release, 29 September. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/more-half-all-schools-remain-closed-borno-state-epicentre-boko-haram-crisis

UNICEF NIGERIA (2017b) ‘Against all odds, girls learn again’, 11 October. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/stories/against-all-odds-girls-learn-again

UNICEF NIGERIA (2017c) ‘Impact evaluation of UNICEF Nigeria girls' education project phase 3 (GEP3) cash transfer programme (CTP) in Niger and Sokoto states’. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/media/1446/file/%20Nigeria-impact-evaluation-UNICEF-Nigeria-girls-education-project-phase-3.pdf.pdf

UNICEF NIGERIA (2019a) ‘UNICEF launches campaign “for every child, every right” on Nigerian children’s day’. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/press-releases/unicef-launches-campaign-every-child-every-right-nigerian-childrens-day

UNICEF NIGERIA (2019b) ‘Psychosocial support for children: a rapid needs assessment in north-east Nigeria’. Available at: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/sites/www.humanitarianresponse.info/files/assessments/psychosocial_support_for_children_assessment_report_june_2020.pdf

UVIN, P. (2007) ‘From the right to development to the rights-based approach: how “human rights” entered development’, Development in Practice, 17(4-5), pp. 597–606. doi:10.1080/09614520701469617

VAISMORADI, M., TURUNEN, H., & BONDAS, T. (2013) ‘Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study’, Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), pp. 398–405. doi:10.1111/nhs.12048

YAYA, S., ODUSINA, E. K. AND BISHWAJIT, G. (2019) ‘Prevalence of child marriage and its impact on fertility outcomes in 34 sub-Saharan African countries’, BMC International Health and Human Rights, 19, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-019-0219-1

Received: July 31st 2021

Accepted: November 3rd 2021

_______________________________

1 Department of Political Science and Diplomatic Studies, Bowen University, Iwo, Osun State Nigeria.

2 Department of Political Science and International Relations, Landmark University, Omu-Ara, Kwara State, Nigeria.

* Corresponding Author: Email: agaptus.nwozor@bowen.edu.ng; agapman1@yahoo.co.uk; ORCID id: orcid.org/0000-0002-9782-6604.

1 See Section 1 of the Child’s Right Act, 2003, Cap C50 Laws of the Federatiosn of Nigeria, 2010. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5568201f4.pdf

2 See the various sections in Child’s Rights Act, 2003. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/5568201f4.pdf

3 See also Nextier SPD, ‘Children in conflict zones’, (29 July 2021). Available at: https://nextierspd.com/children-in-conflict-zones/

4 See ‘UNICEF mission statement’. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/about-us/mission-statement

5 The Child’s Rights Act was adopted in 2003 after several years of disputations and disagreement among diverse stakeholders. Its adoption in 2003 did not enjoy nation-wide support.

6 For the legislative lists, see the second schedule of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended).

7 Section 2, subsection 1 of the Child’s Right Act, 2003 provides “A child shall be given such protection and care as is necessary for the well-being of the child, taking into account the rights and duties of the child's parents, legal guardians, or other individuals, institutions, services, agencies, organizations or bodies legally responsible for the child."

8 See section15, subsection 1 of the Child’s Right Act, 2003.

9 See Nigeria Home Grown School Feeding Strategic Plan 2016-2020 (n.d). Conference ready version. See p. 8. Available at: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/nig169078.pdf

10 Ibid., see p. 8

11 See also UNICEF ‘Education’. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/education

12 See World Bank ‘Population, total – Nigeria’. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.FE.IN?locations=NG&most_recent_value_desc=false

13 British Council (2014) ‘Girls’ education in Nigeria: report 2014 issues, influencers and actions’, See p. 23. Available at: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/british-council-girls-education-nigeria-report.pdf

14 See National Bureau of Statistics, ‘2019 poverty and inequality in Nigeria: executive summary’, 2020. See p. 6. Available at: https://nigerianstat.gov.ng/download/1092

15 See ‘UNICEF mission statement’. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/about-us/mission-statement

16 See ‘UNICEF mission statement’. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/about-us/mission-statement

17 See UNICEF Nigeria, ‘Girls’ education’. Information Sheet, (September 2007). Available at: https://nairametrics.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Fact-sheets-on-Girls-Education.pdf; See also World Bank ‘Girls’ education’, (8 March 2021). Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/girlseducation

18 See News Agency of Nigeria ‘UNICEF says girls education project a huge success’, (21 September 2019), n.p. Available at: https://www.pulse.ng/communities/student/unicef-says-girls-education-project-a-huge-success/hvt4lhr

19 See News Agency of Nigeria Available at: https://www.pulse.ng/communities/student/unicef-says-girls-education-project-a-huge-success/hvt4lhr

20 See News Agency of Nigeria Available at: https://www.pulse.ng/communities/student/unicef-says-girls-education-project-a-huge-success/hvt4lhr

21 See World Bank ‘Girls’ education’, (8 March 2021). Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/girlseducation