Graph 1. Estimated number of fatalities per year.

Source: CVR, 2003b, p. 22.

ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCE IN PERU: A STEP TOWARDS A NATIONAL POLICY TO SEARCH FOR DISAPPEARED PERSONS

AGATA SERRANÒ1

Abstract: This paper aims to explore, firstly, what impact enforced disappearance -committed during the internal armed conflict which occurred between 1980 and 2000 in Peru- had on victims’ family members. Secondly, measures taken by the Peruvian State for the search, exhumation, identification and restitution of the remains of disappeared persons will be examined. Thanks to the analysis of qualitative interviews with leaders of associations dedicated to supporting family members of disappeared persons, this paper will analyse the needs of this group of people, which are still unmet and that constitute a future challenge for the Peruvian state.

Keywords: Transitional justice, disappeared persons, crimes against humanity, internal armed conflict, Peru.

Summary: 1. MATERIAL AND METHODS. 2. ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCE IN PERU: A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY. 3. THE SEARCH FOR DISAPPEARED PERSONS: A LEGACY BRIDGING GENERATIONS. 4. THE HUMANITARIAN APPROACH IN THE SEARCH FOR DISAPPEARED PERSONS: A WAY TO ENSURE THE RIGHT TO TRUTH. 5. CONCLUSIONS.

1. MATERIAL AND METHODS

This research aims to answer the following research questions: What impact has enforced disappearance had on the relatives of those who have suffered from it in Peru? What measures has the Peruvian State taken in order to guarantee the search, exhumation, identification and restitution of the remains of disappeared persons to their loved ones? To answer these questions, this research involved carrying out in-depth qualitative interviews with leaders of associations that support relatives of the disappeared persons. Given their work on the ground, we considered that leaders were particularly aware of the demands of this group of people as they are often relatives of the victims themselves. The interviews were conducted in 2018 in the Peruvian cities of Lima, Ayacucho and Trujillo. Using in-depth qualitative interviews has allowed us to understand the reality of the family members, and obtain a general overview of their perceptions regarding what they experienced and the protection received from the State. In fact, the goal of the technique of qualitative interviewing is to discover the perspective of the subject interviewed, understand their state of mind, their interpretations (Corbetta, 2003, p. 343-373). Michael Patton affirms that “the aim of an interview is to understand how the subjects studied see the world, grasp their terminology and their way of reasoning, comprehend the complexity of their perceptions and individual experiences” (Patton, 1990, p. 290). The main goal of a qualitative interview is to provide a framework within which an interviewee – via a conversation with the interviewer – can express how they feel in their own words. However, an interview should not only be considered a means of accessing knowledge about people’s behaviours and individual traits, but also a way of accessing knowledge about social phenomena (Olaz, 2008, p. 26).

Our interview script was based mainly on the following key matters:

― How the interviewee’s life was changed as a result of their relative/s disappearance and what actions they undertook to search for their family member/s;

― The reaction by the family to the disappearance of a family member and by the socio-political environment;

― The protection received (or the lack of it) from public institutions;

― What needs/rights remain met/unmet;

― The meaning of truth, memory and justice for a family member of a disappeared person;

The type of qualitative interview we used was that of a semi-structured interview, as this modality allows interviewees to express themselves more freely. Similarly, it gives the interviewer greater freedom as they are not necessarily obliged to follow a specific order in the way the questions addressing the relevant topics of the research are asked.

Although part of this research consisted in collecting and analysing primary sources using the qualitative interview research technique, in addition we consulted secondary sources, mainly in Spanish and English, such as articles from specialised journals, books, legislation, institutional and/or private reports, judgements, newspaper articles, etc.

As for the sample of interviewees, they are 8 leaders of the most active associations in the defence of the rights of disappeared persons who responded to our request for an interview. Their associations are providing services especially in Lima, Ayacucho, two of the cities where very high levels of human rights violations were recorded. As we used the technique of qualitative interviewing, our goal was not to obtain a statistically representative sample. We did not, therefore, use criteria that would allow for proportionality between the number of interviewees and the total number of disappeared persons, nor did we aim for the sample to reproduce the characteristics of a given statistical population on a smaller scale. In order to fully understand the phenomenon studied, our goal was to gather a diverse sample of participants with different experiences of victimisation. This sample was gathered by adopting the “snowball sampling” technique according to which initial contacts with the first interviewees are usually provided by local entities that exist in the interviewee’s community and which are related to the topic being researched. In our case, these entities were associations and foundations of family members that we contacted, especially in Lima and Ayacucho, whose members/leaders agreed to be interviewed. This technique – used to approach groups that are particularly difficult to contact – allows the interviewer to obtain access to other possible participants thanks to contacts suggested by the initial interviewees. This is why, during our fieldwork, many interviewed put us in touch with others they knew personally (Corbin & Strauss, 2008).

The 8 participants were interviewed individually in Spanish, avoiding direct questions that could hurt their sensitivity or lead to a re-victimisation, following the ethical criteria for qualitative interviewing of vulnerable subjects (Varona, 2015). All of the interviews were recorded with the prior written and signed consent of each interviewee, who was informed of the objectives of the research. The interviews were accurately transcribed and a copy was given to each interviewee. Given the sensitivity of the information that the interview might contain, the consent included the option of not revealing the identity of the participants. Once transcribed, the interviews were analysed using Atlas.ti 8 qualitative analysis software, allowing us to obtain a graphic representation of the testimonies that we will show in this article.

We would like to stress that the interview excerpts chosen cannot be considered to be the official narrative of any association or group of victims interviewed. The choice of these interviewees over others involved no personal or collective discrimination. In fact, the main goal of this research is to divulge the tragedy of all the thousands of people who unjustly suffered this crime against humanity and not to exclude any of them. Likewise, this research can be considered as a preliminary study and a starting point for future work, hopefully based on a larger fieldwork analysis.

2. ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCE IN PERU: A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY

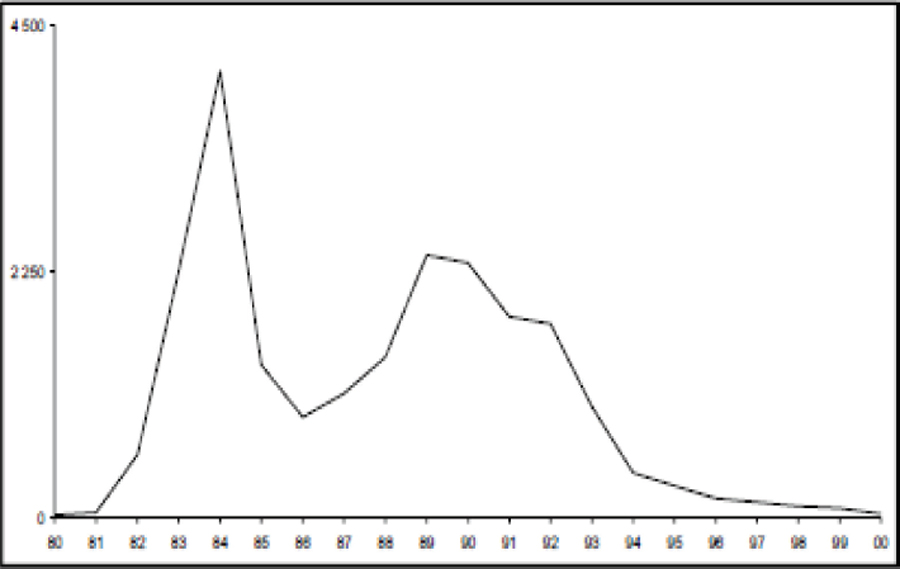

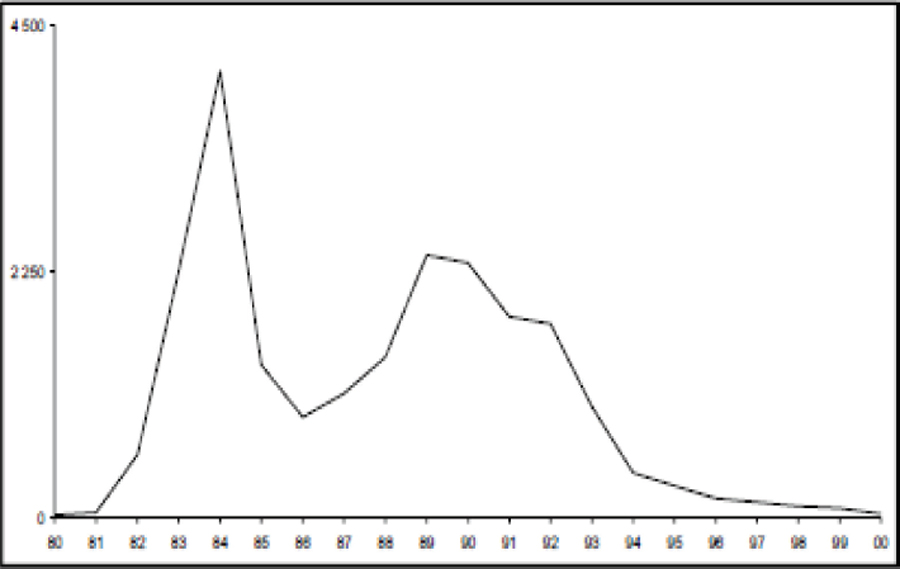

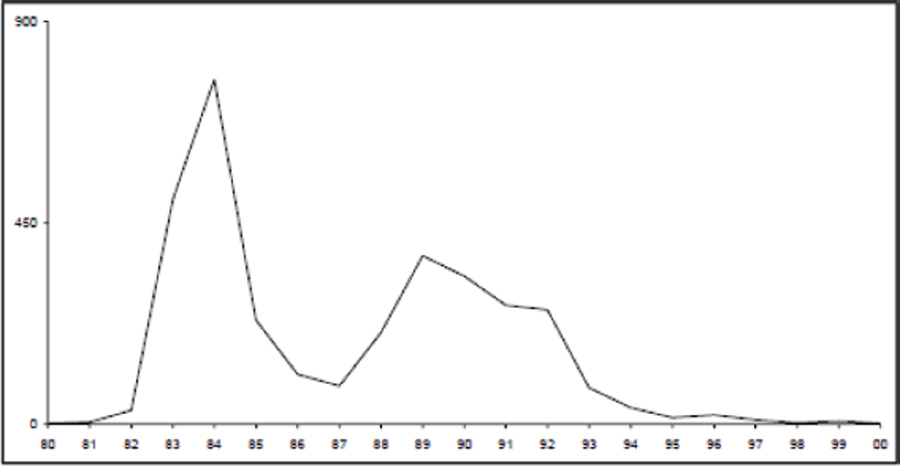

Before going into detail on the impact of enforced disappearance, it is important to underline that between 1980 and 2000, Peru experienced a period of unprecedented violence - known as the internal armed conflict - which led to at least 69,280 fatalities (Graph 1), according to the estimate by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR), created in 2001 to shed light on these events (Degregori, 2014). According to Graph 2, those responsible for these victims were subversive groups, such as Shining Path (PCR-SL; 54%) and the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA; 1%); the police forces and the armed forces (AGENTES DEL ESTADO; 36%); self-defence committees and rondas campesinas (CADS; 2%), unknown and other actors (NO DETERMINADOS Y OTROS; 7%)2.

Graph 1. Estimated number of fatalities per year.

Source: CVR, 2003b, p. 22.

Graph 2. Estimated percentage of number of victims caused by each group.

Source: CVR, 2003b, p. 21.

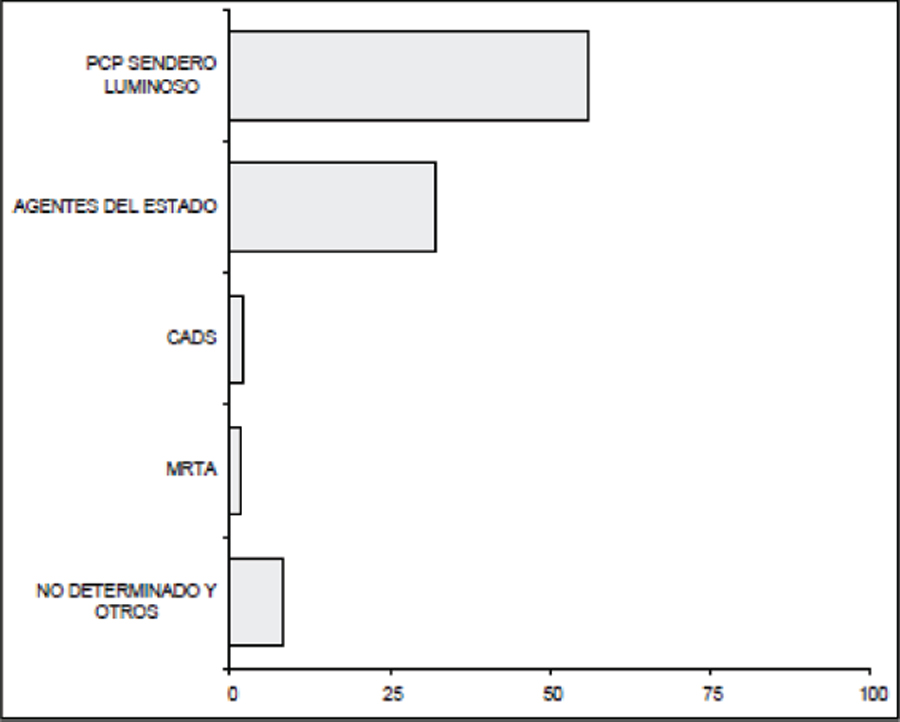

These actors committed different human rights violations, such as assassinations, arbitrary or extrajudicial executions, kidnappings, enforced disappearances and cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment or punishment, among others (Graph 3). Most of the victims were killed in the south-central region of Peru, in particular from the departments of Ayacucho, Junín, Huánuco, Huancavelica and Apurímac. However, the district of Lima and the north-eastern and central Amazon rainforest were also severely affected by the violence. These regions and areas accounted for 97% of the total number of victims, as well as the greatest number of attacks, destruction of infrastructure and loss of social capital. The majority of those killed were peasant farmers from the poorest and most marginalised areas of the country, Quechua-speaking inhabitants from rural Andean areas, and members of different indigenous communities from forest regions (CVR, 2003a, p. 12).

Graph 3. % of crimes and human rights violations and other incidents reported per each act3.

Source: CVR, 2003g, p. 274.

Of all the human rights violations committed during this period of violence, enforced disappearances were notably dramatic. The CVR initially reported that 8,558 persons had disappeared. It also cited the existence of 4,644 burial sites, of which 2,200 were located in the 10 departments most affected by the internal armed conflict (CVR, 2003b, p. 23). The work of the CVR has been continued by a number of institutions that have devoted themselves to recording and classifying disappeared persons.

In 2007, for example, the Peruvian Team of Forensic Anthropology (EPAF) submitted a report to the International Committee of the Red Cross with the records of 13,271 disappearances. In 2008, the National Coordinator for Human Rights (CNDDHH) also presented a report that compiled 3,469 new cases in addition to those presented by the CVR, increasing the number of disappeared persons to 12,027 (COMISEDH, 2012, p. 20). Furthermore, in 2011, the Legal Medicine Institute of the Public Prosecutor’s Office of Peru stated that 15,731 persons had disappeared during the internal armed conflict, 4,241 of whom were from the Department of Ayacucho alone (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2012).

From 2016 onwards, and thanks to Law 30470 ‘Law on the search for persons who disappeared during the period of violence 1980-2000’, the first steps for a future national policy were made to address these matters; thanks to this Law, the General Directorate for the Search of Disappeared Persons (DGBPD) was created under the umbrella of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, which is in charge of the search process for disappeared persons. In 2018, this Directorate created the National Registry of Disappeared Persons and Burial Sites (RENADE), the first official centralised registry, which organised and investigated the data of more than twenty-thousand persons who were reported to have disappeared from 1980 to 2000. In its second statistical report (DGBPD, 2021), the DGBPD specified that disappeared persons in Peru are 21,918. The whereabouts of 7,404 persons remains unknown or uncertain, while the whereabouts of 6,664 persons are allegedly known but there is no legal proof of their location. Locating, exhuming, identifying and returning the remains to families constitutes a pending task for Peru, and these latest – and unfortunately not yet final – figures, make it one of the countries with the most disappeared persons in Latin America (LUM, 2018).

But what is enforced disappearance? The CVR defines enforced disappearance as: ‘the disappearance and deprivation of freedom of one or more persons by agents of the State or by those who act with its authorisation, support, or acquiescence, or by individuals or members of subversive organisations, followed by an absence of information or a refusal to acknowledge that deprivation of freedom or to give information on the whereabouts of that person’ (CVR, 2003c, p.114). Enforced disappearance as a generalised and systematic practice is considered to be a crime against humanity by the Statute of Rome –that established the International Criminal Court – in its article 7, paragraph 1 (International Criminal Court, 1999). As can be seen in Graph 4, enforced disappearance was a generalised practice particularly from 1983 to 1985 and from 1989 to 1993. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (COIDH) concluded in its Report (number 56/99) that: ‘[…] between 1989 and 1993, there existed in Peru a systematic and selective practice of forced disappearances, carried out by agents of the Peruvian State or were tolerated by said State. Said official practice of enforced disappearances was part of the fight against subversion, although in many cases it harmed people who had nothing to do with the activities related to dissident groups’ (Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, Report 56/99, par. 68).

Graph 4. Number of enforced disappearances reported to the CVR by year.

Source: CVR, 2003c, p. 81.

The process began with the victim being detained usually by masked and armed agents who would violently take the suspect to a police station or military location. There, the detainee was interrogated and almost always tortured in order to extract information that was eventually useful in the fight against subversiveness. Sometimes they were released, but other times they were arbitrarily executed. In order to destroy the evidence of these executions, the bodies were made to disappeared or disposed of by mutilating them, incinerating the remains, throwing them into rivers or into other inaccessible places, burying them in mass graves or scattering body parts in different places to make identification difficult (CVR, 2003c, p. 114).

Moreover, enforced disappearance in Peru was a systematic practice due to the existence of a complex power structure that devised, organised and carried it out: it was done according to a standardised modus operandi that identified, selected and processed the victims, and also involved the disposal of their bodies, delegating these functions to different groups: to military officers, to police agents or to civilians.

According to the CVR, it was possible to expand this systematic practice thanks to the broad authority held by military officers when states of emergency were declared, when respect for human rights within the framework of the fight against subversiveness was truly precarious (CVR, 2003c, p. 115).

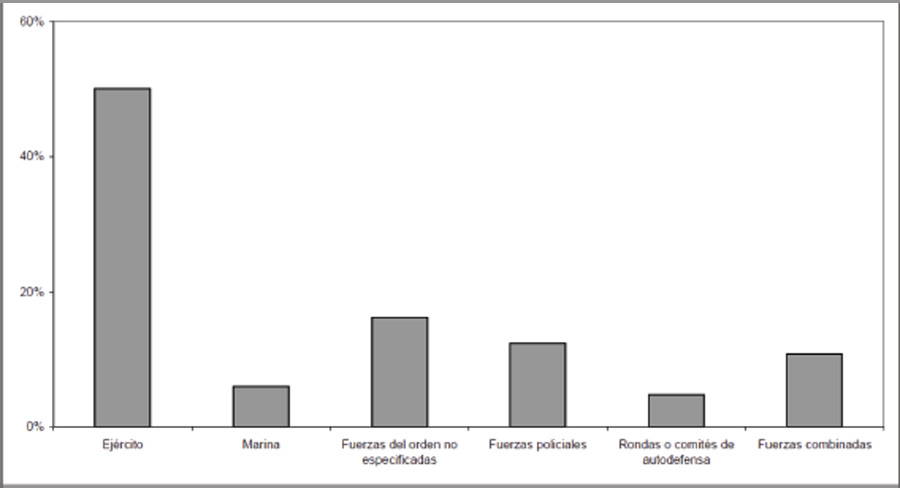

As can be seen in Graph 5, the main group responsible for enforced disappearances was the Peruvian army, followed by law enforcement and police agencies, the Navy, rondas campesinas and self-defence committees4. In order to commit these types of criminal acts, whose goal was to defeat PCP-SL and MRTA terrorism, a number of paramilitary groups were set up within the armed and police forces during the conflict. One of these was the Colina Group, whose members belonged to the Peruvian Army Intelligence Service (SIE), which ‘carried out a State policy consisting of identifying, controlling and disposing of those suspected of belonging to insurgent groups or who opposed the regime of former President Alberto Fujimori, through systematic actions of indiscriminate extrajudicial executions, selective killings, enforced disappearances and torture’ (Inter-American Court of Human Rights, Case of La Cantuta vs. Peru, 2006: paragraphs 40 and 80).

Graph 5. Percentage of cases of enforced disappearance per group responsible.

Source: CVR, 2003c, p. 81.

In addition, the Colina Group was responsible for the Barrios Altos and La Cantuta massacres (Jara, 2013), for which the Peruvian state was condemned by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and former President Alberto Fujimori was put in prison. Furthermore, enforced disappearances could be perpetuated as a systematic practice also due to the inaction of the Public Prosecutor’s Office to investigate and punish those responsible for the crimes committed, most of whom still remain unpunished and have not revealed the whereabouts of the victims (CVR, 2003c, p. 117). In fact, only some of these agents were convicted for having carried out this crime, as stated in Report 159 of the Ombudsman’s Office, which states that up to 2008 only 339 people had been prosecuted, out of which 264 were in the Army, 47 were in the Peruvian National Police, 17 were in the Navy, and 11 were civilians convicted for crimes committed mainly in the city of Ayacucho (Ombudsman’s Office, 2008, p. 139).

3. THE SEARCH FOR DISAPPEARED PERSONS: A LEGACY BRIDGING GENERATIONS

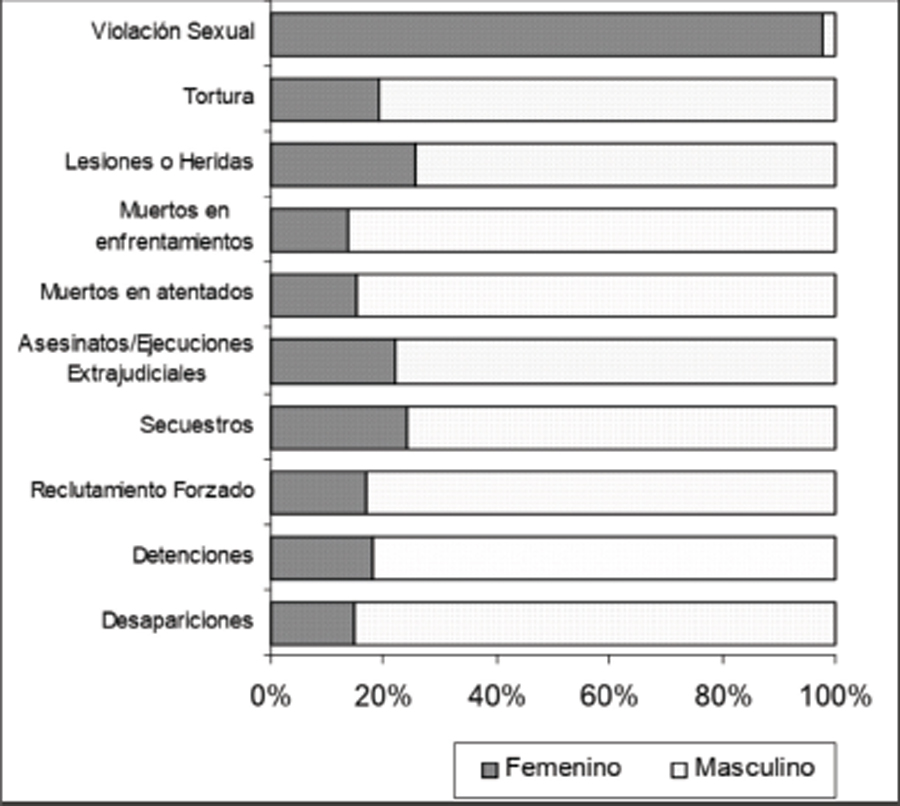

A fact that must be highlighted – as can be seen in Graph 6 – is that the fatalities and disappeared persons were mainly male: this means that a significant number of women witnessed the traumatic loss of family members and loved ones5. This is also confirmed in Report 55 of the Ombudsman’s Office, according to which 87.8% of the victims of enforced disappearance in Peru were male and 12.2% were female; 66.8% of the victims were between 15 and 34 years of age (Ombudsman’s Office, 2004, p. 65).

Enforced disappearance and/or assassination (plus other crimes committed against their family members) leads to significant personal and family trauma, not only because of the void left by the loved one but also because of the sudden impact that said loss had on their lives, creating a before-and-after moment that can never be forgotten. In fact, because of the violence, many women were widowed and were obliged to become the head of the household, being responsible for the work in the fields, in addition to doing the housework and bringing up the children. Their economic situation worsened drastically as they were not able to find a way to feed their fatherless children. These circumstances drove many children to start working at a very young age; it was impossible to go to school or they had to find the money to do so, sometimes not only for themselves but also for their younger siblings (Alvites & Alvites, 2007, 134 et seq.).

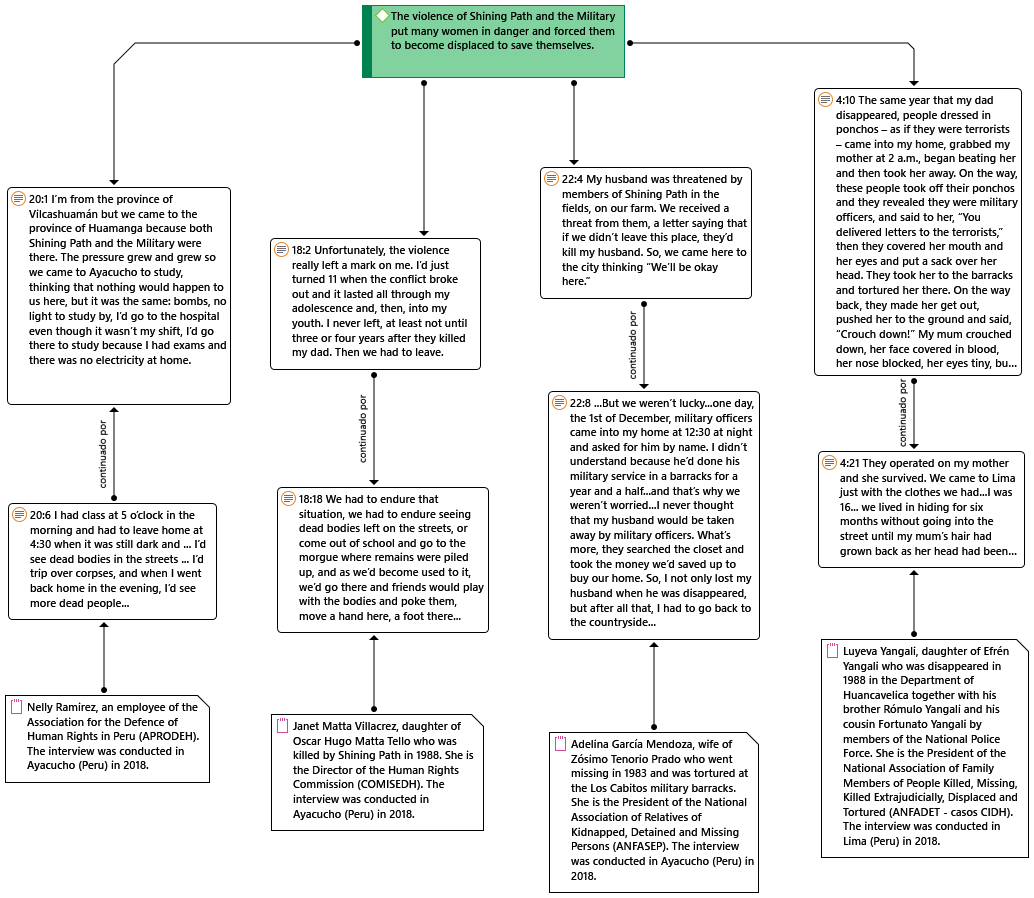

Faced with enforced disappearance or assassination, in many cases, the only way to stay safe was to move from the countryside to the city and, sometimes, from the city back to the countryside again, trying to continuously flee the advance of a changing enemy that one day could be a subversive group and the next day the armed forces, among others (Chart 1). This can be seen in the following charts according to the testimonies of victims of subversive groups and human rights violations committed by state agents, we interviewed in Peru in 2018, whose interviews we analysed with Atlas.ti 8 qualitative research analysis software.

Chart 1. The violence of Shining Path and agents of the State forced many women to become displaced to save themselves.

Source: Own work done with Atlas.ti 8 qualitative research analysis software, based on qualitative interviews conducted in Peru.

According to these witness accounts, the disappearance or assassination of a family member led to multiple traumas, in particular for the women as they not only had to cope with the loss of a loved one, but also had to leave their homes and properties and flee, struggle with the cultural uprooting that forced displacement involves as well as the social stigmatisation in their new place of abode. At times, their Andean or indigenous features, the fact that they were illiterate or hardly knew any Spanish, had little money, were stigmatised because of the violence they had suffered, meant they had to endure social exclusion, discrimination and undeserved blame, both in the place they had left behind as well as in their new place to live (CVR, 2003e).

However, despite all the suffering they endured, during the conflict many Peruvian women decided to react with resilience in the face of adversity, trying to improve their personal situation by working and studying in order to ensure a better future for themselves and their families. In this traditional society they had to overcome many challenges, as women were exclusively assigned the roles of ‘mother’ or ‘wife’, roles only associated with taking care of the home and rearing children (Alvites & Alvites, 2007, 134 et seq.).

Graph 6. Violations against human rights reported to the CVR according to the sex of the victim6.

Source: CVR, 2003g, p. 273.

Undoubtedly, one of the greatest challenges that Peruvian women have had to face during the conflict and in the post-conflict period is the search for their disappeared relatives. This search has led them to visit hospitals, police stations, military bases, prisons and even morgues, exposing them to new crimes such as arrest, torture, threats, rape, among others. Too often they have had to endure the blatant impunity enjoyed by the perpetrators, often State agents who concealed the truth from them and hindered them from obtaining justice (Ortiz Perea, 2017).

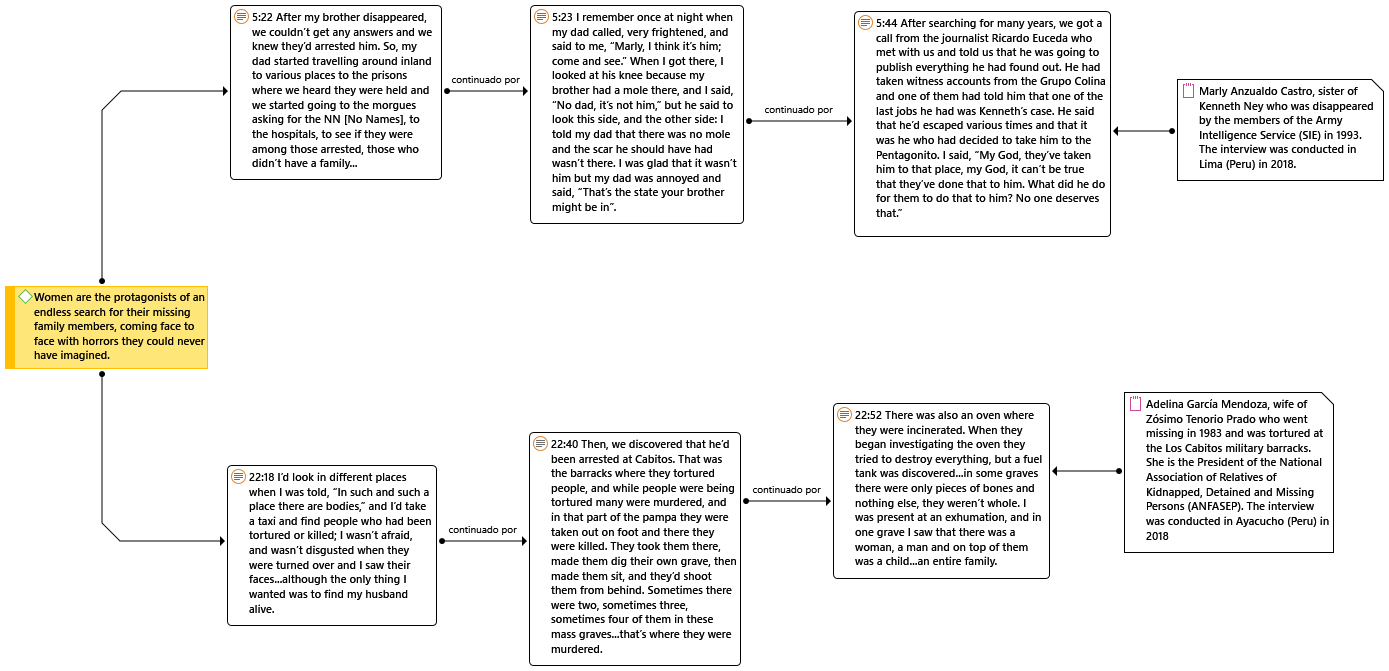

At other times, their search led them to uncover the facts, and discover an inhumane and horrific truth: to destroy the evidence of the executions carried out, the bodies of their family members were mutilated, remains were incinerated or were thrown into rivers or into other inaccessible places, buried in mass graves, or body parts were scattered in different places to make identification difficult. That is the account given by Marly (Chart 2), whose brother Kenneth Ney Anzualdo Castro disappeared in 1993 and was taken – together with his friend Martin Javier Roca Casas – to the basement of a building in Lima known as the ‘Pentagonito’ (Little Pentagon); this was the headquarters of the Army Intelligence Service (SIE), where many disappeared persons were incinerated in crematorium ovens. These facts were corroborated by Peru’s Supreme Court in 2016 when it tried Vladimiro Montesinos Torres, Nicolás de Bari Hermoza Río and Jorge Enrique Nadal Paiva – members of the Peruvian Army Intelligence Service – and found them guilty of being mediate perpetrators of the crime of enforced disappearance (Supreme Court of Justice of the Republic of Peru, 2016). The ruling of the Supreme Court complied with the internal judicial process, as the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (COIDH) had ordered the Peruvian State to do in the case of Anzualdo Castro vs. Peru7. However, due to the fact that the remains were incinerated, other very important aspects of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruling have not been fulfilled, such as the location, exhumation, identification and return of the mortal remains of the disappeared persons to their family members (Supreme Court of Justice of the Republic of Peru, 2016).

Chart 2. In some cases, the search for disappeared family members led Peruvian women to discover an abhorrent truth.

Source: Own work done with Atlas.ti 8 qualitative research analysis software, based on qualitative interviews conducted in Peru.

A similar case is that of Adelina García Mendoza, whose husband (Chart 2), Zósimo Tenorio Prado, was disappeared in 1983. He was tortured at the Domingo Ayarza barracks, better known as ‘Los Cabitos’, in Ayacucho. In 2017, the National Criminal Court of the Supreme Court issued a historic judgement with regard to the violations of human rights carried out at this barracks, proving that in the 1980s hundreds of people were arbitrarily arrested and tortured in order to make them confess to their alleged affiliation to Shining Path, before disappearing. Furthermore, it was proved that at ‘La Hoyada’, an area adjacent to ‘Los Cabitos’, mass graves were found, where 109 people had been buried. It was also proved that a crematorium oven had existed there, used to incinerate the remains of victims to make their bodies definitively disappear. In this very same place, despite the terrible discoveries, the family members are fighting to create a Sanctuary of Memory at La Hoyada so that their loved ones will be remembered. The ruling finally sentenced Pedro Paz Avendaño, head of the Intelligence Detachment of Ayacucho, to 23 years in prison, and Humberto Orbegozo Talavera, Head of ‘Los Cabitos’ Barracks to 30 years.

These are just some of the thousands of stories that have been forgotten for decades and are still unknown; stories of women who, in addition to having suffered the loss of a loved one, were subjected to numerous re-victimisations or secondary victimisations (Echeburúa & Gerrica, 2006, p.198) because not only did they suffer harm and a violation of their rights, but they were also humiliated, blamed by the perpetrators; ignored and unprotected by public authorities; and marginalised, excluded and stigmatised by the rest of civil society.

However, despite the repeated victimisations they suffered, during the internal armed conflict the mothers, wives, siblings and children of the victims of violence, in addition to saving their own lives, tried to help each other by creating ties of solidarity among themselves. This mutual help led to the emergence of a human rights movement, whose aim was to address different urgent matters, among which were: finding disappeared family members; and advocating public policies to support rights regarding the truth, justice, memory and reparation (CVR, 2003f, p. 295). With these main goals, these women and their family members gave rise to a human rights movement that involved different associations.

In 1983, after the Armed Forces entered Ayacucho, the Association for the Defence of Human Rights in Peru (APRODEH) was set up and which, even today, offers numerous services, including legal aid to the family members of victims. Thanks to their work – and that of many other associations offering legal aid to the family members of victims – many cases have been tried in court with the aim of ending the impunity of those responsible for the violations committed and obtaining justice. In many cases, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has condemned the State of Peru; it has issued 29 rulings, most of which were linked to acts committed during the internal armed conflict. Consequently, as of today, of all the states that ratified the American Convention on Human Rights (CADH), Peru is the country most condemned for violations against human rights (Ugarte Boluarte, 2014). These rulings confirm that the State of Peru, by committing assassination, carrying out massacres and arbitrary executions, among other practices, notably violated the right to life. Similarly, by torturing and inflicting other cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment it specifically infringed the right to physical and moral integrity; by kidnapping and enforced disappearances it notably violated the right to personal freedom; by carrying out trials with ‘faceless judges’ it violated the right to due process (Salado Osuna, 2004).

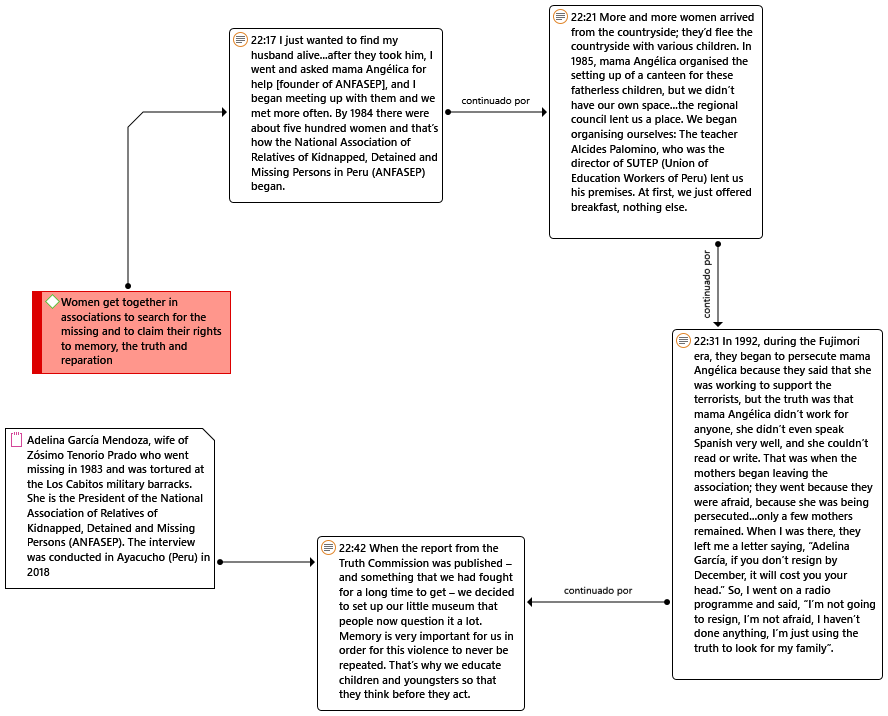

In 1985, the National Human Rights Coordinator was set up. Bringing together a number of associations, it became an effective instrument for victims to find support and legal advice; a point of reference, which, however, over the years has weakened (CVR, 2003f, p. 295). Meanwhile, in Ayacucho, in 1983, the first organisation of women and family members of those who disappeared was set up: the National Association of Relatives of Kidnapped, Detained and Disappeared Persons (ANFASEP). As explained in Chart 3 by its current President, Adelina García Mendoza, its goals include caring for fatherless children and their mothers who left the countryside fleeing the violence, by setting up a communal canteen; trying to find disappeared family members; publicly denounce the crimes committed via peaceful demonstrations, protests, marches and all kinds of activities to create awareness in civil society and to public authorities on the need for truth and reparation for the family members of disappeared persons. Furthermore, ANFASEP was the first Peruvian association to set up a Museum of Memory in Ayacucho so that the thousands of family members brutally taken by the conflict are not forgotten. This museum has been visited by scholars from around the world, yet regrettably continues to be attacked by a sector of the population, which, from the start, has tried to weaken the strength of the human rights movement (Crisóstomo, 2019, p. 129). Today, sadly, many of the mothers/women who founded this association have died without having found the bodies of their loved ones.

Chart 3. The search for disappeared family members led women to associate and fight for their rights to be respected.

Source: Own work done with Atlas.ti 8 qualitative research analysis software, based on qualitative interviews conducted in Peru.

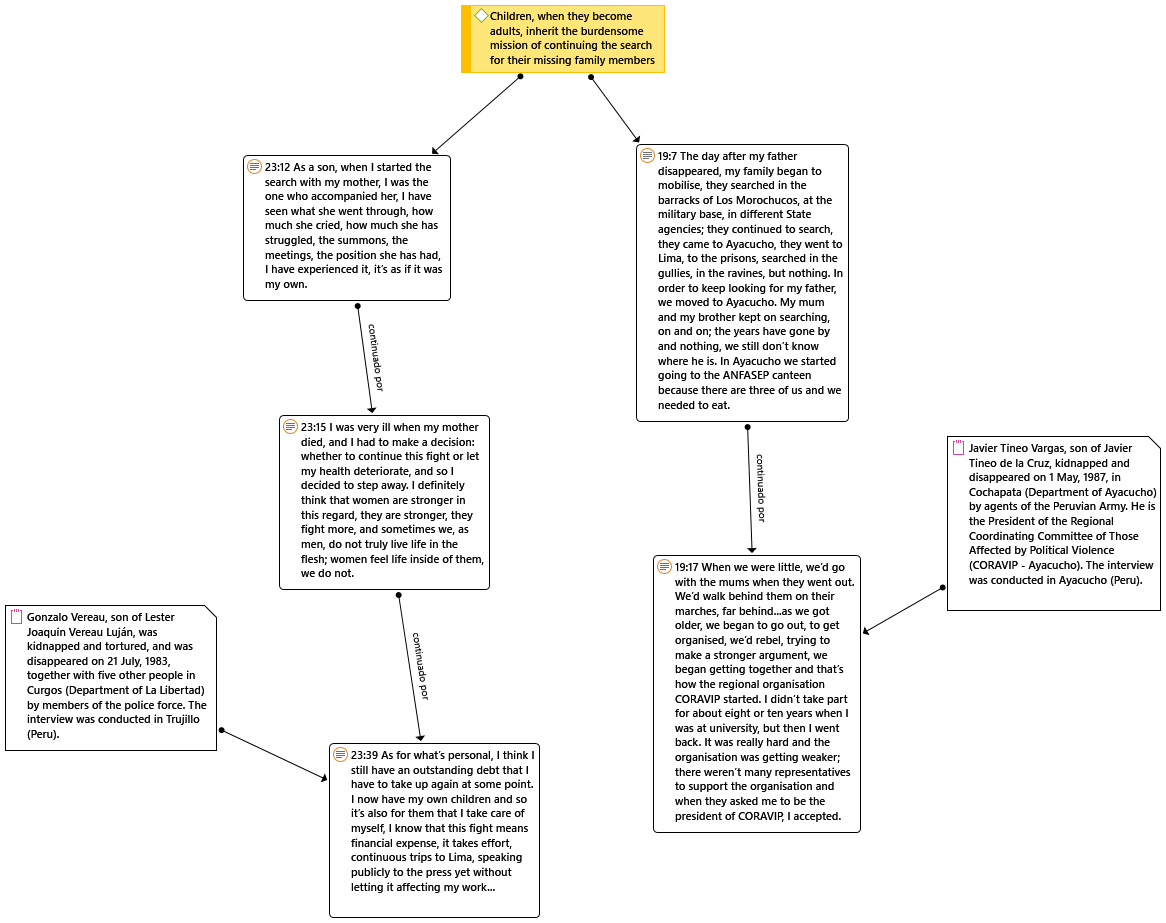

Their tireless search has often been inherited by the next generation, a mission for the children who supported them on the gigantic undertaking they endured. As can be seen from Chart 4, some of them have been able to pick up the baton and continue fighting in the name of their family members; others, unfortunately, for various reasons have not been able to continue with the burdensome task they inherited. However, it is important to stress that when the responsibility for searching for disappeared persons – and finding their remains – falls on family members, it constitutes a serious re-victimisation for them because the search for their loved ones is an obligation of the State, which should guarantee their right to truth, justice, memory and reparation.

Chart 4. The search for disappeared family members has been inherited by the next generation.

Source: Own work done with Atlas.ti 8 qualitative research analysis software, based on qualitative interviews conducted in Peru.

4. THE HUMANITARIAN APPROACH IN THE SEARCH FOR DISAPPEARED PERSONS: A WAY TO ENSURE THE RIGHT TO TRUTH

In the post-conflict era, despite the permanent stigmatisation to which they were exposed, the leaders of the human rights movement contributed to the setting up of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR), in which – for the first time ever – some 16,000 people offered their testimony, revealing the horrors to which they were subjected during the conflict. The CVR Report endorsed many of the movement’s demands, recommending, among other issues, the adoption of specific policies for reparation.

In light of the CVR’s recommendations, a reparation policy was implemented in 2005 via Law 28592 (Approval of the Comprehensive Reparation Plan for Victims of Violence). Thanks to this legislative instrument, the following were created: the High Level Multisectoral Commission (CMAN) that is in charge of monitoring the State’s actions and policies in the areas of peace, collective reparation and reconciliation (Ulfe, 2013); the Reparations Council (CR), in charge of creating the Central Registry of Victims (RUV) and of the accreditation, identification and individualisation of victims and different reparation programmes (collective reparations for the more than 600,000 displaced persons throughout the country who had to leave their land and homes due to violence by armed groups); and the Individual Economic Reparations Programme (PREI), in charge of reparations regarding health and education, symbolic reparations, access to and support for housing, and the restitution of rights (Lerner Febres, 2007).

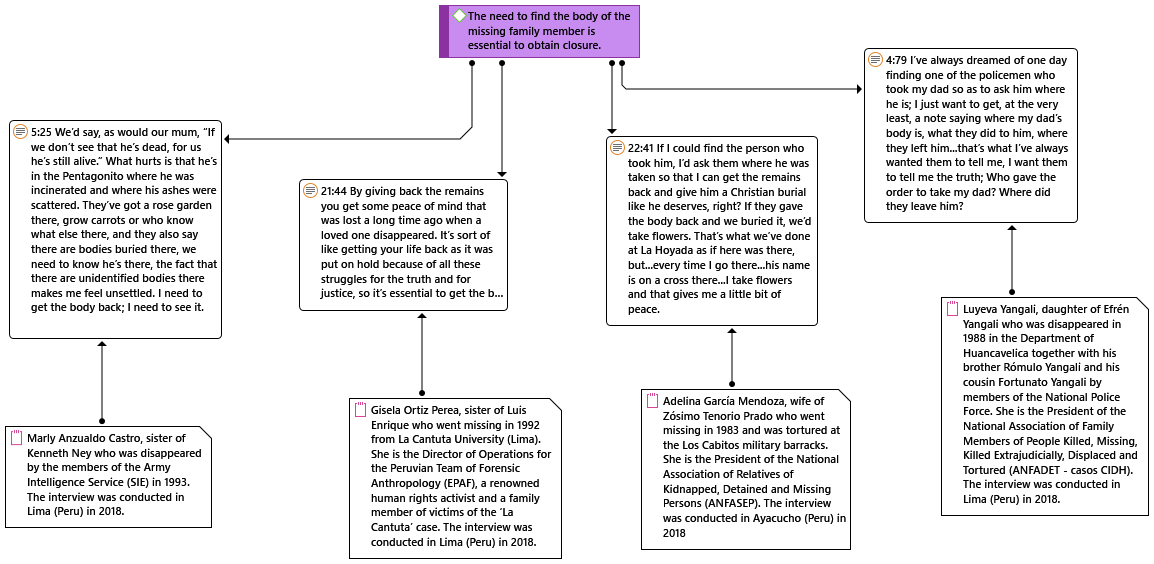

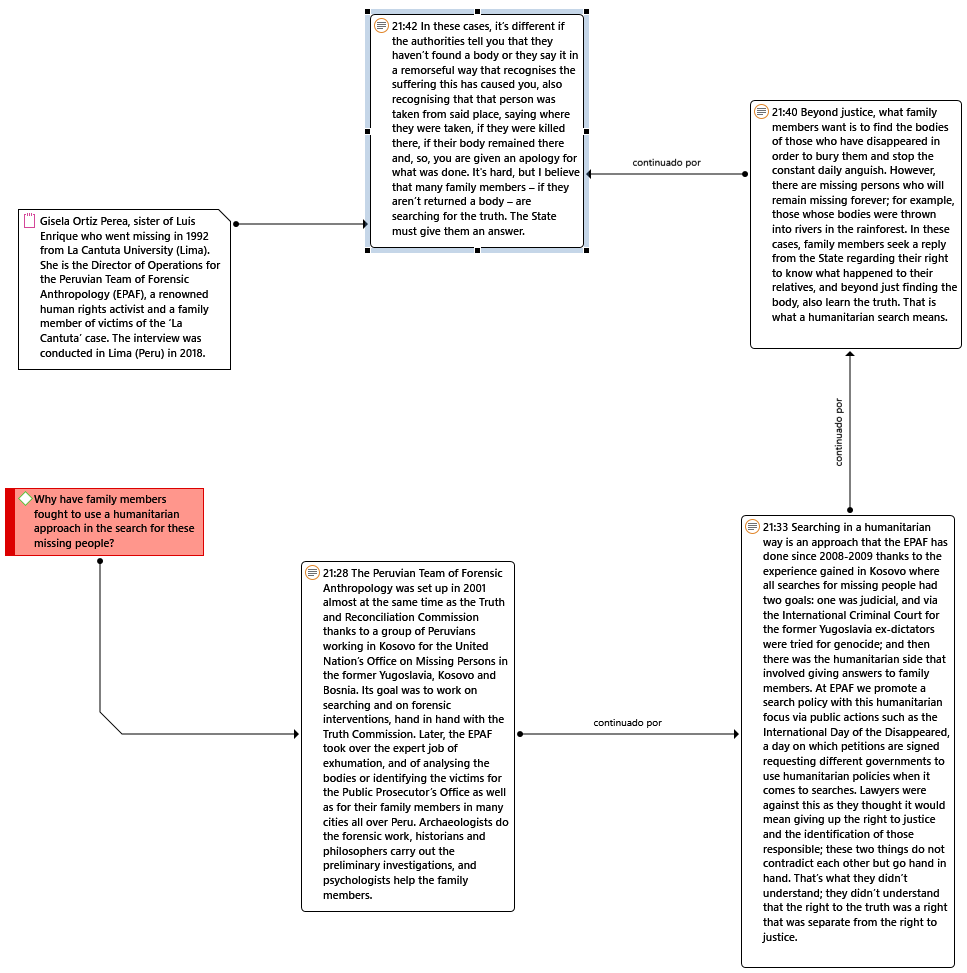

In addition to demands for reparations, which have been insufficiently implemented so far (Iris Jave, 2021), another very important claim made by family members of disappeared persons is, without a doubt, knowing the truth about what happened to their loved ones, finding their whereabouts and, when possible, to have their mortal remains returned to them. On the one hand, it is essential for family members to know the truth about what happened to their loved ones in order to be able accept their loss, cope with their absence and obtain closure (Chart 5). On the other hand, it is crucial to close this open wound not only on a personal level but also for civil society. However, it should be noted that, in interviews by family members, the need to know the truth about what happened is not necessarily accompanied by a demand to obtain full judicial truth that would allow the identification of those responsible and for them to be judged and punished. In fact, as can be seen in Charts 5 and 6, the greatest need of family members of disappeared persons is the recovery of the human remains of their loved ones (Losonczy & Robin, 2021). According to the account of Gisela Ortiz, Director of Operations of the Peruvian Team of Forensic Anthropology (EPAF), in Chart 6, this is why the human rights movement – advised by teams of experts – promoted the adoption of the humanitarian approach to the search for disappeared persons during the post-conflict era (Iris Jave, 2018). The main goal and priority of this approach is to satisfy the right to truth for family members and their need for closure; it aims to try to clarify what happened and, when possible, locate, exhume and return the remains of their loved ones, regardless of whether the perpetrators of that crime are identified, tried and convicted (EPAF & CNDDHH, 2008). In line with this approach, thanks to the tireless and peaceful struggle of family members of the disappeared persons, “Law 30470 on the search for persons who disappeared during the violence of 1980-2000” was passed in 2016. This Law aims to search for, recover, analyse, identify and return the human remains of disappeared persons by adopting the humanitarian approach. Article 2 of said Law understands the humanitarian approach to be: ‘the attention focused on relieving suffering, uncertainty and the need to offer answers to the family members of the disappeared persons. Prioritising a humanitarian approach means guiding the search to the recovery, identification, restitution and dignified burial of the human remains of the disappeared persons in such a way that it has a restorative effect for the families, yet without encouraging or hindering the attribution of criminal responsibilities’ (Law 30470, Art.2).

Chart 5. The need to find the body of the disappeared family member is essential to obtain closure.

Source: Own work done with Atlas.ti 8 qualitative research analysis software, based on qualitative interviews conducted in Peru.

Chart 6. Choosing the humanitarian approach to ensure the right to truth.

Source: Own work done with Atlas.ti 8 qualitative research analysis software, based on qualitative interviews conducted in Peru.

Before said law was approved, the search process for disappeared persons was only carried out when the Public Prosecutor’s Office had evidence on the whereabouts of a disappeared person while a case was being investigated. The location, exhumation and identification of disappeared persons therefore occurred exclusively within the framework of a judicial investigation. Following the approval of Law 30470, the process of searching for disappeared persons is now under the competence of the Directorate for the Search for Disappeared Persons (DGBPD) under the umbrella of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights and consists of three phases, formalised via the ‘Directive to Standardise the Process of Searching for Disappeared Persons with a Humanitarian Approach’ (Directive 001-2017- JUS/VMDHAJ-DGBPD). In the first phase, the DGBPD carries out a humanitarian investigation that consists of all the investigative actions undertaken to generate, compile, verify and analyse information regarding contexts and circumstances related to cases of disappeared persons. During this phase, a non-judicial investigation is carried out on the specific case and focuses on areas and contexts, conducting in-situ interviews, creating a psychosocial diagnosis and identifying, evaluating and recording possible burial sites where the person/s being searched for might be found.

The second phase involves a joint intervention with the Public Prosecutor’s Office: it consists of all the actions which are carried out to recover, analyse and evaluate the evidence, which, after being scientifically analysed, may allow disappeared persons to be identified and returned to their family members in order for them to be buried with dignity. In this phase, the two institutions work together to identify burial sites and exhume the remains, analyse the skeletal remains and other evidence, and carry out their identification process. This identification process is now more effective thanks to the approval of the 1398 legislative decree of 2018, which allowed the DGBPD to create a genetic data bank that allows the DNA of the family members of the victims to be compared with the skeletal remains found in mass graves (El Comercio, 2018).

The third phase – which the DGBPD is in charge of – corresponds to the end of the process. In this phase, family members are informed about the fate of their loved ones, family reunions are organised (if the disappeared person has been found alive), human remains are returned (if they are found), symbolic ceremonies are held (in cases where bodies are not exhumed or not found), as are ceremonies to mark the end of the search process.

Thanks to the adoption of this humanitarian approach, the DGBPD offers family members psychosocial support throughout the search process, i.e. a set of actions on an individual, family, community and/or social level that are aimed at preventing, addressing and coping with the psychosocial impact of the disappearance, which also helps the search process for disappeared persons to be carried out.

Family members are supported at every stage of the forensic investigation and during the return of any remains to ensure their recovery and emotional well-being (Law 30470, Art.2, Letter e). In addition, the DGBPD coordinates a set of actions implemented by different sectors of the State so that family members can participate in the processes to search for, recover, analyse, identify, return and bury the remains of disappeared persons with dignity (material and logistical support to family members).

Therefore, thanks to the approval of Law 30470, and the consequent adoption of the humanitarian approach, the process of searching for disappeared persons is no longer exclusively linked to a judicial investigation but is more focused on ensuring the right to truth for family members, regardless of whether or not there is an ongoing judicial investigation.

Notwithstanding the steps that have been taken to design a policy for the search for disappeared persons and reparations in Peru, there remain different challenges that need to be addressed in the near future. In fact, in spite of having institutionalised the search process the challenge that needs to be addressed is that a massive amount of work still remains to be done before family members can enjoy a full right to the truth as the whereabouts of many thousands of disappeared persons are still unknown. Finally, the Covid-19 pandemic is also making this process extremely difficult due, on the one hand, to restricted mobility and, on the other, because of cuts in the budget allocated to the search for disappeared persons.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This paper, firstly, has examined how enforced disappearance manifested itself in Peru during the internal armed conflict (1980-2000), its modus operandi and why it is considered to be a crime against humanity. Secondly, via the testimonies of leaders of associations who are fighting to defend human rights, the experience of family members in relation with their need to know the truth about what happened and to recover the mortal remains of their loved ones have been explored. Thirdly and finally, we have studied how the Peruvian State has tried to satisfy said demands of the human rights movement via the approval of Law 30470 and by adopting a search process with a humanitarian approach.

Answering to the first research question, the impact of enforced disappearance on the relatives of victims has been particularly traumatic in Peru, especially for women. Actually, since victims of enforced disappearance were mostly male, women suffered multiple losses, having had to cope not only with the absence of a loved one, but also with the family burden alone, often dealing with forced displacement and social stigmatisation in the new place of residence.

Undoubtedly, one of the greatest challenges that Peruvian women have had to face during the conflict and in the post-conflict period is the search for their disappeared relatives. This search has led them to visit hospitals, police stations, military bases, prisons and even morgues, exposing them to new crimes such as arrest, torture, threats, rape, among others. Too often they have had to endure the blatant impunity enjoyed by the perpetrators, often State agents who concealed the truth from them and hindered them from obtaining justice. At other times, their search led them to uncover the facts, and discover an inhumane and horrific truth.

However, thanks to the analysis of the interviews we carried out in Peru, it can be concluded that, despite all the injustices suffered, many of them have fought against impunity, being a civic example, leading the creation of a peaceful movement in defence of human rights which, on the one hand, has tried to overcome the State’s neglect of those affected and, on the other hand, has fought and continues to fight for greater effectiveness of the rights to truth, justice, memory and reparation.

In response to our second research question, the measures taken by the Peruvian State in order to guarantee the search, exhumation, identification and restitution of the remains of disappeared persons are innovative but unfortunately still insufficient. Despite the steps that have been taken to design a national policy for the search for disappeared persons and reparations in Peru, this paper concludes that at least two urgent challenges still need to be addressed in the near future. Firstly, a huge amount of work remains to be done in order for family members to recover the remains of disappeared persons as the whereabouts of many thousands of disappeared persons are still unknown. Coping with the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic is the second challenge that must be stressed; it is making the search process much more difficult due to restricted mobility and cuts in the budget allocated to it.

The partial results obtained in this preliminary research certainly constitute a starting point for further work to explore how to consolidate the national policy of searching for missing persons in Peru in order to guarantee the right to truth to their families.

REFERENCES

Primary sources

Interview with Adelina García Mendoza, wife of Zósimo Tenorio Prado who went disappeared in 1983 and was tortured at the Los Cabitos military barracks. She is the President of the National Association of Relatives of Kidnapped, Detained and Disappeared Persons (ANFASEP). The interview was conducted in Ayacucho (Peru) in 2018.

Interview with Gisela Ortiz Perea, sister of Luis Enrique who went disappeared in 1992 from La Cantuta University (Lima). She is the Director of Operations for the Peruvian Team of Forensic Anthropology (EPAF), a renowned human rights activist and a family member of victims of the ‘La Cantuta’ case. The interview was conducted in Lima (Peru) in 2018.

Interview with Janet Matta Villacrez, daughter of Oscar Hugo Matta Tello who was killed by Shining Path in 1988. She is the Director of the Human Rights Commission (COMISEDH). The interview was conducted in Ayacucho (Peru) in 2018.

Interview with Marly Anzualdo Castro, sister of Kenneth Ney who was disappeared by the members of the Army Intelligence Service (SIE) in 1993. The interview was conducted in Lima (Peru) in 2018.

Interview with Nelly Ramirez, an employee of the Association for the Defence of Human Rights in Peru (APRODEH). The interview was conducted in Ayacucho (Peru) in 2018.

Luyeva Yangali, daughter of Efrén Yangali who was disappeared in 1988 in the Department of Huancavelica together with his brother Rómulo Yangali and his cousin Fortunato Yangali by members of the National Police Force. She is the President of the National Association of Family Members of People Killed, Disappeared, Killed Extrajudicially, Displaced and Tortured (ANFADET - casos CIDH). The interview was conducted in Lima (Peru) in 2018.

Gonzalo Vereau, son of Lester Joaquin Vereau Luján, was kidnapped and tortured, and was disappeared on 21 July, 1983, together with five other people in Curgos (Department of La Libertad) by members of the police force. The interview was conducted in Trujillo (Peru).

Javier Tineo Vargas, son of Javier Tineo de la Cruz, kidnapped and disappeared on 1 May, 1987, in Cochapata (Department of Ayacucho) by agents of the Peruvian Army. He is the President of the Regional Coordinating Committee of Those Affected by Political Violence (CORAVIP - Ayacucho). The interview was conducted in Ayacucho (Peru).

Secondary sources

ALVITES E. & ALVITES L., Mujer y violencia política. Notas sobre el impacto del conflicto armado interno peruano. Feminismo/s, (9) 2007, pp. 121-137. https://doi.org/10.14198/fem.2007.9.09

CORBETTA P. (2003), Metodología y técnicas de investigación social. Madrid: McGrawhill.

CORBIN, J. & STRAUSS, A. (2008), Basics of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

Comisión de Derechos Humanos (2012). Plan Regional de investigaciones antropológico forenses para Ayacucho, estrategias de investigación y lineamientos generales. Ayacucho: COMISEDH.

CRISÓSTOMO, M. (2019). Memories between Eras. ANFASEP’s leaders and after Peru’s Internal Armed Conflict. Latin American Perspectives, 46(5), 128-142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X19856901

CVR (2003a). Informe Final de la Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. «La violencia en las regiones». Tomo IV, Sección Tercera, Capítulo 1. Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. https://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/

CVR (2003b). Informe Final de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Compendio estadístico, Anexo 3. Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. https://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/

CVR (2003c). Informe Final de la Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. «Las desapariciones forzadas». Tomo VI, Sección Cuarta, Capítulo 1.2. Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. https://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/

CVR (2003d). Informe Final de la Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. «Los asesinatos y las masacres». Tomo VI, Sección Cuarta, Capítulo 1.1. Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. https://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/

CVR. (2003e). Informe Final de la Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. «Violencia y desigualdad de género». Tomo VIII, Segunda Parte, Capítulo 2.1. Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. https://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/

CVR (2003f). Informe Final de la Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. «El movimiento de derechos humanos», Tomo III, Cap. 3.1. Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. https://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/

CVR (2003g). Informe Final de la Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. «Violencia sexual contra la mujer». Tomo VI, Sección Cuarta, Capítulo 1.5. Comisión de la Verdad y la Reconciliación. https://www.cverdad.org.pe/ifinal/

DEGREGORI, C. I. (2014). Heridas abiertas, derechos esquivos. Derechos humanos, memoria y Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos.

ECHEBURÚA & GUERRICA. (2006). Especial consideración de algunos ámbitos de victimización. En E. T. Baca, Manual de víctimología. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch.

EL COMERCIO. (1 September 2018). Aprueban decreto legislativo para la creación de banco de datos genéticos. El Comercio.

EPAF & CNDDHH. (2008). Desaparición Forzada en el Perú: El aporte de la investigación antropológica forense en la obtención de la evidencia probatoria y la construcción de un paraguas humanitario. 2008. Lima: EPAF.

General Directorate for the Search of Disappeared Persons, Reporte Estadístico n° 2, Registro Nacional de Personas Desaparecidas y de Sitios de Entierro (RENADE), 31 de julio de 2021, Obtenido de: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minjus/informes-publicaciones/2154045-reporte-estadistico-n-2-registro-nacional-de-personas-desaparecidas-y-de-sitios-de-entierro

International Criminal Court (1999). Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (1999). Report 56/99. Case of Eudalio Lorenzo Manrique at al. San José de Costa Rica: Inter-American Commission of Human Rights

Inter-American Court of Human Rights (2009), Case of Anzualdo Castro vs. Perú (Judgment, 22 September 2009). San José de Costa Rica: Inter-American Commission of Human Rights.

Inter-American Court of Human Rights (2006), Case of La Cantuta vs. Peru (Judgment, 29 November 2006). San José de Costa Rica: Inter-American Commission of Human Rights.

JARA, U. (2013). Ojo por ojo. Lima: Planeta.

JAVE, I. (2021), La humillación y la urgencia. Políticas de reparación y posconflicto en el Perú. LIMA. Fondo Editorial de la PUCP.

JAVE, I. (2018). Organizaciones de víctimas y políticas de justicia: construyendo un enfoque humanitario para la búsqueda de personas desaparecidas. LIMA. IDEHPUCP. Obtenido de: http://cdn01.pucp.education/idehpucp/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/25164640/ford-anfasep_1pagina-final-isbn.pdf

LERNER FEBRES, S. (2007). Justicia y reparación para las víctimas de la violencia política. Revista Páginas, XXXII (207), 52-58.

LOSONCZY A. M. & ROBIN V. Retorno de cuerpos, recorrido de almas. Exhumaciones y duelos colectivos en América Latina y España, Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.

LUM. (24 de Abril de 2018). Presentan lista del Registro Nacional de Personas Desaparecidas y Sitios de Entierro (Renade). LUM. Obtenido de https://lum.cultura.pe/noticias/presentan-lista-del-registro-nacional-de-personas-desaparecidas-y-sitios-de-entierro-renade

MANRIQUE-VALLIER D. & BALL P. (2019), Reality and risk: A refutation of S. Rendón’s analysis of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s conflict mortality study, Research and Politics, (1) 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168019835628

Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores (2012). Documento de Trabajo sobre las Medidas adoptadas por diferentes sectores en relación a la Resolución AG/RES (XLI-O/11) “Las personas desaparecidas y la asistencia a sus familiares”. Lima: Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores.

OLAZ A. (2008), La entrevista en profundidad, Oviedo: Septem ediciones.

Ombudsman Office (2008). A 5 años de los procesos de reparación y justicia en el Perú. Balance y desafíos de una tarea pendiente. Lima: Ombudsman Office.

Ombudsman Office (2004). Violencia Política en el Perú: 1980-1996. Un acercamiento desde la perspectiva de género. Lima: Ombudsman Office.

ORTIZ PEREA, G. (2017). Hasta encontrarlos. La identidad como derecho: Retos y lecciones en la búsqueda de los desaparecidos en el Perú. Revista Memoria (23), IDEHPUCP, Ed., pp. 9-19.

PATTON, M. Q. (1990), Qualitative evaluation and research methods, Newbury Park: Sage Publication.

REYES, V. (21 de Agosto de 2017). Justicia para las víctimas de Los Cabitos, un análisis del fallo, LIMA, IDEHPUCP. Obtenido de https://idehpucp.pucp.edu.pe/notas-informativas/justicia-las-victimas-los-cabitos-analisis-del-fallo/

RENDON S. (2019), Capturing correctly: A reanalysis of the indirect capture–recapture methods in the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Research and Politics, (1) 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018820375

SALADO OSUNA, A. (2004). Los casos peruanos ante la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Trujillo: Normas Legales.

Supreme Court of Justice of the Republic of Peru (2016), Sótanos del SIE Case, Supreme Court of Justice of the Republic of Peru Judgement. Available in: https://doi.org/10.51378/eca.v71i746.3188

UGARTE BOLUARTE, R. (2014). Los derechos humanos en el Perú: una mirada al cumplimiento de las sentencias supranacionales dictadas por la Corte IDH vs. el Perú. Revista Lex, XII(14). https://doi.org/10.21503/lex.v12i14.636

ULFE M. E. (2013). ¿Y después de la violencia qué queda? Victimas, ciudadanos y reparaciones enel contexto post-CVR en el Perú. Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

ULFE, M.E. & ROMIO S. (2021), “Género y violencia: desmontando el perfil de víctima del Informe final de la Comisión de la Verdad y Reconciliación en Perú”, en Gómez D., Bernal A., González J., et al (eds.), Comisiones de la verdad y género en países del sur global: miradas decoloniales, retrospectivas y prospectivas de la justicia transicional. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, pp. 373-410.

VARONA G. (2015), Guía general de buenas prácticas en el trato con víctimas del terrorismo que evite la victimización secundaria. San Sebastián: Instituto Vasco de Criminología. Y Gobierno Vasco, Secretaría General para la Paz y la Convivencia. https://www.euskadi.eus/contenidos/proyecto/victimas_proyecto006/es_def/adjuntos/Guia_general_buenas_practicas.pdf

Received: January 4th 2022

Accepted: April 14th 2022

_______________________________

1. Ramón y Cajal Researcher, Departament of Political Science and International Relations, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain (agata.serrano@uam.es).

2. Some scholars question the reliability of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission estimations. On this issue, see the debate between Rendon (2019) and Manrique-Vallier & Ball (2019).

3. In order of appearance in the Graph 3, translated in English the crimes committed are: Assassinations/Extrajudicial Executions, Arrests, Torture, Disappearances, Kidnappings, Injuries and Bodily Harm, Recruitment by Force, Killed in Confrontations, Sexual Violence, Killed in Attacks.

4. Shining Path (PCP-SL) was responsible for individual and collective murders (massacres) committed in particular in the rainforest and the Peruvian Andes and were a systematic and generalised practice, especially in the Department of Ayacucho. According to the cases reported to the CVR, PCP-SL was responsible for 11,021 murders and 1,543 enforced disappearances; this brings the number of victims attributed to this terrorist group to a total of 12,564 people, making it 1.7 times higher than the number of deaths and disappearances attributed to State agents, which amounts to 7,391 (CVR, 2003d, p. 20).

5. For a critical approach on this issue, see Ulfe & Romio (2021), who proved that among victims of enforced disappearance there were many more women than those recorded by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

6. In order of appearance in the Graph 7, translated in English the violations committed are: Sexual Violence, Torture, Injuries and Bodily harm, Killed in Attacks, Assassinations/Extrajudicial Executions, Kidnappings, Recruitment by Force, Arrests, Disappearances.

7. Anzualdo Castro vs. Peru (COIDH Ruling, 22 September 2009).