Figure 1: Seventeen UN SDGs

Source: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/news/communications-material/

CROSS-EMBEDDED RELATIONSHIP NATURE OF HUMAN RIGHTS-RELATED TREATIES AND INSTRUMENTS WITH ENVIRONMENT-RELATED SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

Abstract: It is imperative that Treaties & Instruments and United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) must be analysed considering their interdependencies and mutually reinforcing nature. The paper examines the Cross Embedded Relationship (CER) nature of core Human Rights-related Treaties & Instruments (HR-T&I) in Environment-related SDGs (E-SDG) in driving a structured transformation process toward inclusive economic growth, adhering to human rights values that are environmentally centric and sustainable in the true sense. Some core HR-T&I explicitly recognise CER, as observed in textual analysis. The study reveals a varied level of the Cross Embedment Relationship Index (CERI) between the provisions of core HR-T&I and E-SDG, thereby indicating the importance of human rights principles in E-SDG and the significance of environment orientation in core HR-T&I. Linking core HR-T&I provisions with E-SDG and extra-legal compliance mechanism of SDGs can produce positive synergies in realising SDG objectives.

Keywords: Sustainable development, Human Rights, international treaties & instruments, UN SDGs, environment targets, cross embedded relationship, cross embedded relationship index.

Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION AND STUDY BACKGROUND: 1.1 Study background, 1.2 Selection of E-SDG, 1.3 Aim of the paper; 2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK PRINCIPLES OF CER BETWEEN CORE HR-T&I AND E-SDG; 3. TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CORE HR-T&I IN THE CONTEXT OF E-SDG: 3.1 Approach, 3.2 UDHR, 3.3 ICERD, 3.4 ICESCR, 3.5 ICCPR, 3.6. CEDAW, 3.7 CRC, 3.8 ICRMW, 3.9 CRPD; 4. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION ON CER OF CORE HR-T&I WITH E-SDG: 4.1 Approach, 4.2 Analysis of CER of core HR-T&I with E-SDG 12, 4.3 Analysis of CER of core HR-T&I with E-SDG 13, 4.4 Analysis of CER of core HR-T&I with E-SDG 14. 4.5 Analysis of CER of core HR-T&I with E-SDG 15; 5. QUANTITATIVE CHARACTERISATION OF CER AND CROSS EMBEDDED RELATIONSHIP INDEX; 6. IMPORTANCE OF CER NATURE OF CORE HR-T&I WITH E-SDG AND CONCLUSION.

1. INTRODUCTION AND STUDY BACKGROUND

1.1. Study background

Internationally recognised Human Rights (IHR) and the environmental law frameworks have not yet been integrated despite interrelated and interconnected relations between the two fields as recognised by the 1972 Stockholm Declaration (UN, 1972). Environmental degradation and IHR abuse are two major issues in the contemporary world, but a common international law protecting the environment and IHR is unfound (Olawuyi, 2014; Akyuz, 2021).

United Nations (UN) seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), along with their 169 targets, as shown in Figure 1, are components of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SD), as adopted by the UN General Assembly Summit in 2015. Seventeen SDGs and their corresponding targets pave an equitable roadmap for a development that blends three dimensions of sustainability: environmental-economical-social (EES) facets, factoring IHR. Promotion, protection and fulfilment of IHR and environmental sustainability are viewed as complementary objectives at the core of SD. Furtherance to the UN Conference on Human Environment held in Stockholm in 1972, the linkage relationship between IHR and the environment has received increased attention. States, the Human Rights Council (HRC), the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the World Bank Inspection Panel, international institutions and civil society laid substantial interest in understanding the relationship between IHR and the environment.

Figure 1: Seventeen UN SDGs

Source: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/news/communications-material/

Strongly grounded in IHR standards, the 2030 Agenda endeavours to leave no one behind and anchor equality and non-discrimination, as enumerated below.

“(i) The 2030 Agenda is unequivocally anchored in IHR; (ii) The SDGs offer a new, more balanced paradigm for more sustainable and equitable development; (iii) The SDG targets are closely aligned with IHR standards; (iv) However, where there are gaps or inconsistencies, it will be critical to ensure that implementation of the targets is consistent with IHR law; (v) The 2030 Agenda aims to combat inequalities and discrimination and “leave no one behind”, and contains a strong commitment to the disaggregation of data; (vi) The new agenda includes perhaps the most expansive list of groups to be given special focus of any international document of its kind; (vii) The SDGs are universal and indivisible, and all goals must be implemented for all people in all countries; (viii) A strong accountability framework should be established at national, regional and global levels, including accountability for non-state actors; (ix) A IHR-sensitive SDG indicator framework is needed, to monitor progress for all people, everywhere.”(OHCHR, 2017)

SDG finds various references to the IHR (Spijkers, 2020). When analysing IHR anchorage of each SDG and its corresponding targets, it becomes evident that the 2030 Agenda and IHR are intertwined and inextricably tied together (Feiring and König-reis, 2020) Connecting legal scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers working on IHR and biodiversity issues, the report of SwedBio (Ituarte-lima, 2020) provides pathways and strategies that could enable humankind to reverse the intimidating tendencies of ecological deterioration, achieving a clean and healthy environment together with the SDG keeping IHR in the centre stage and leaving no-one behind (Ituarte-lima, 2020).

Various international and regional Treaties and Instruments (T&I) on different subjects have evolved over time. Many research studies, international reports and institutions have focused on analysing T&I in the context of SDGs (Harrigton, 2021; Huan et al., 2021). SDGs progress analysis incorporating provisions of T&I is a recent and evolving phenomenon. Thus, the provisions of legally binding and nonbinding Human Rights-related Treaties and Instruments (HR-T&I) and targets of SDGs must be analysed considering their interdependencies and mutually reinforcing nature. Only a little attempt has been made in the past in this direction. HR-T&I are effective in improving the environment, and HR-T&I act as a proactive facilitator in fostering SD and environment and IHR law to further SDGs progress.

It is conventional to analyse the direct correlation between the provisions of environment-related T&I and environment-related goals (E-SDG). HR-T&I are predominantly pertinent to the principle of inclusive growth while guaranteeing that no one is eliminated or discriminated against in resource sharing, development process, and growth strategy. Qualitative mapping of provisions of core HR-T&I and IHR is found in the literature (The Office of the Legal Counsel in collaboration with the Communicable Diseases and Department Environmental Determinants of Health, 2022). Despite SD being promulgated in international and national legal contexts in a structured manner, there is still a gap witnessed in integrating environmental and IHR principles. Hence analysing the Cross Embedded Relationship (CER) nature of HR-T&I in E-SDG assumes great importance in this context. In the past, some attempts to link SDG and a few HR-T&I have been carried out (The Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2008; Wernham, 2016; The Danish Institute of Human Rights, 2017). The long-overdue recognition of the IHR and environment nexus and the subsequent IHR turn in the environment and climate change litigation are also highlighted in the literature (Fraser and Henderson, 2022). However, the CER nature of HR-T&I in E-SDG is rarely analysed comprehensively, or analyses are confined to SDG dealing with health or water (Scanlon, Cassar and Nemes, 2004) or right to food and nutrition (Vivero Pol and Schuftan, 2016; Aller Celia, Romero Elena and Carvajal Marta, 2018) or clean energy or related areas (Spijkers, 2020). This perceived gap needs to be addressed as a holistic approach by examining various legally binding and nonbinding core HR-T&I provisions and their linkage with the E-SDG.

1.2. Selection of E-SDG

Seventeen 17 SDGs and corresponding 169 targets, in addition to their attribute of indivisibleness, inclusiveness and universality, lay considerable and equal importance on EES dimensions of SD with environmental dimensions integrated into socio-economic development plans (Asian Development Bank, 2019). According to United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), "environmental dimensions" could imply a total of 86 targets out of 169 targets that either directly or indirectly pursue to reduce environmental damage or accentuate the pivotal role of natural resources and ecosystem services in guaranteeing human well-being and prosperity (UNEP, 2016). For practical reasons, the present paper could not consider all the 86 targets identified by UNEP (UNEP, 2016). Instead, the paper focus on E-SDG, namely 12, 13, 14, and 15 and their corresponding Environment-related Target (ET-SDG) proposed to have a direct relationship with responsible consumption and production, climate change, and sustainable marine and terrestrial ecosystems management.

Thus the E-SDG for the present study would include:

“(i) E-SDG 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns i.e. ET-SDG 12.1-12.8, 12.a-12.c; (ii) E-SDG 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts i.e. 13.1-13.3, 13.a-13.b; (iii) E-SDG 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for SD, i.e. ET-SDG 14.1-14.7, 14.a-14.c; and (iv) E-SDG 15: Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss, i.e. ET-SDG 15.1-15.9, 15.a-15.c” (UN General Assembly, 2015, 2017).

1.3. Aim of the paper

The main aim of the present article is to examine the CER nature of core HR-T&I in E-SDG for driving a metamorphic transformation process toward inclusive economic growth, adhering to IHR values that are environmentally-centric and sustainable in a true sense. The perceived gap is addressed through:

a. A systematic review of legally binding and nonbinding core HR-T&I, E-SDG, their relevance and applicability in SDG analysis. For practical reasons, the core HR-T&I selected for the study (OHCHR, 2014) include (i) Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), 1948 (UN General Assembly, 1948); (ii) International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), 1965 (UN General Assembly, 1965); (iii) International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), 1966 (UN General Assembly, 1966b); (iv) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), 1966 (UN General Assembly, 1966a); (v) Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), 1979 (UN General Assembly, 1979); (vi) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), 1989 (UN General Assembly, 1989); (vii) International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (ICRMW), 1990 (UN General Assembly, 1990); (viii) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), 2007 (UN General Assembly, 2006)3;

b. Understanding of theoretical framework principles of CER between core HR-T&I and E-SDG;

c. Analysing the CER nature of core HR-T&I in E-SDG that are necessary to be monitored for

“(i) sustainable consumption and production patterns; (x) combating climate change; (xi) conservation and sustainable usage of marine resources; and (xii) protection, restoration and promotion of sustainable use of the terrestrial ecosystem.” (UN General Assembly, 2015).

d. Development of a quantitative measure of CER and relative quantitative analysis of CER both from core HR-T&I and E-SDG perspectives.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK PRINCIPLES OF CER BETWEEN CORE HR-T&I AND E-SDG

This section discusses the major environmental threats and their impact on IHR; how environmental protection contributes to the realisation of IHR; the work of the IHR treaty bodies regarding the CER between IHR and the environment; and theoretical issues in the CER between IHR and the environment.

The doctrine of SD can be traced to the Stockholm Declaration (UN, 1972). The Declaration recognised that there is “a fundamental right to freedom, equality and adequate conditions of life, in an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity and well-being.”(UN, 1972), thereby apparently recognising a right to an adequate environment. However, it lacks the force of a binding treaty.

2030 Agenda is overtly anchored in IHR principles, recognises IHR as foundational to Agenda, is strongly reflected in several SDGs and their associated targets, and is indistinguishably linked. Many SDGs and their corresponding targets correspond to essential dimensions of States’ IHR commitments, as outlined in core HR-T&I and other documents (The International Planned Parenthood Federation, 2015) relating to IHR. Seventeen SDGs aimed to realise IHR for everyone, and elements of IHR and labour standards are manifested in several manners in more than 90% of SDG targets. The inclusive growth model approach reflects basic principles of IHR of non-discrimination and equality. IHR reinforces SDGs, and it is possible to achieve SDGs only when principles of participation, accountability and non-discrimination are respected. A significant level of convergence witnessed between IHR and the 2030 Agenda suggests that prevailing IHR mechanisms can facilitate evaluating and implementing the 2030 Agenda and SDGs. It underlines the Agenda’s grounding in UDHR and core HR-T&I and emphasises States’ responsibilities to respect, protect and promote IHR and fundamental freedoms for all, without distinction of any kind. The report of Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation elucidates the manner of support provided by IHR to the 2030 Agenda, the reason for considering an IHR-based approach for the 2030 Agenda implementation, and how global and national IHR mechanisms can be leveraged in reinforcing SDG monitoring and review (Feiring and König-reis, 2020).

Atmospheric-related activities create environmental impacts as they exacerbate air emissions, resulting in air pollution, climate change and ozone depletion. Land degradation, deforestation and desertification threaten the terrestrial environment, mostly of a regional nature. It is imperative to understand that development and the water environment are linked to environmental problems, including degradation of water quality, depletion of fresh water, and pressures on the oceans. Hazardous waste, chemical contaminants and pollution are common environmental threats. Biodiversity loss and natural and man-made disasters are other forms of threats to the environment. All of these factors are destructive to the environment, have negative impacts on human well-being, and have potential and visible impacts on IHR.

Environmental degradation may impair the attainment of IHR. It is decisively recognised that “environmental degradation can and does adversely affect the enjoyment of a broad range of IHR” (UN Human Rights Council, 2013). The numerous environmental threats have or potential to have an adverse impact on all aspects of IHR and well-being. Environmental protection must be ensured to protect IHR and improve human well-being.

It is imperative to consider environmental protection as an IHR-connected issue for a host of reasons like (i) IHR’s view focuses directly on environmental impacts on individual life, health, privacy and property rather than on States or the environment at large; (ii)) A focus on IHR can serve to guarantee enhanced environment quality standards based on the obligation of States to take adequate measures to control various forms of pollution affecting health and private life; (iii) The relationship between IHR and the environment helps to promote the rule of law in environmental-related matters as Governments are held responsible for noncompliance in enforcing the law and lack of control on environmental pollution, violations and nuisances, including those caused by companies; (iv] IHR considerations have the potential to facilitate large scale public participation in environmental decision-making, environment and social impact assessment studies, access to justice and access to information; (v) A IHR approach may more categorically encompass public interest elements in environmental protection as an IHR”(Boer and Boyle, 2014). A high-quality environment is a core component of IHR to life, health, and associated rights like the right to clean water, adequate housing, and food (Lewis, 2018).

As observed by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), Stockholm Declaration (UN, 1972) reflects a “general recognition of the interdependence and interrelatedness of IHR and environment” (UN Human Rights Council, 2009). OHCHR’s conclusion is also supported in other work wherein IHR law includes obligations relating to the environment that encompass both procedural and substantive obligations (UN Human Rights Council, 2013). Despite literature available on the environment and IHR law and its relevance to SDGs (Environmental Law Dimensions of Human Rights, 2015; GaiaTascioni, 2016; Arts, 2017; Lewis, 2018; Dulume, 2019; Nikolaou, 2019; Orellana, 2020), the relationship between IHR and the protection of the environment in international law is by no means simple or direct (Boyle, 2012). Environmental dimensions of IHR law are rarely discussed in the literature, notwithstanding increasing environmental cases in IHR jurisprudence.

The resolution of the HRC acknowledged numerous important components of the CER between IHR and the environment as detailed below (UN General Assembly, 2011b, 2011a):

“(a) SD and the protection of the environment can contribute to human well-being and the enjoyment of IHR;

(b) Environmental damage can have negative implications, both direct and indirect, for the effective enjoyment of IHR;

(c) While these implications affect individuals and communities around the world, environmental damage is felt most acutely by those segments of the population already in vulnerable situations;

(d) Many forms of environmental damage are transnational in character, and that effective international cooperation to address such damage is important in order to support national efforts for the realisation of IHR;

(e) IHR obligations and commitments have the potential to inform and strengthen international, regional and national policymaking in the area of environmental protection and promote policy coherence, legitimacy and sustainable outcomes” (UN General Assembly, 2011b, 2011a).

The 16 Framework Principles on Human Rights and the Environment, based primarily on international instruments and decisions by international institutions, were presented to the UN HRC in 2018 by the Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment (Knox, 2018; Knox, J.H. and Morgera, 2022), setting out the obligations of States under IHR law because they relate to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment and provide a sturdy basis for understanding and implementing IHR obligations relating to the environment (Knox, 2018; Knox, J.H. and Morgera, 2022).

Philosophical, theoretical and legal perspectives of IHR and the environment are discussed in the literature (Leib, 2011). The theoretical discussion involves two core issues: (i) analysing the nature and type of the relationship between IHR and the environment; and (ii) examining the scope of a new IHR for a healthy environment for recognition by the international community.

Three major theoretical approaches are identified in the literature (UN General Assembly, 2011a; Boer and Boyle, 2014; Kaltenborn, Krajewski and Kuhn, 2020) for the above-cited first issue;

(i)positioning the environment as a “pre-condition to the enjoyment of IHR.”; thereby accentuating that life and human dignity are only possible to achieve whenever people have access to an environment with certain basic qualities. Air, water, land, soil and noise pollution causing environmental degradation can affect the attainment of specific rights, such as the rights to life, food and health;

(ii)IHR is coined as “tools to address environmental issues, both procedurally and substantively”; thereby emphasising the possibility of using IHR to achieve adequate levels of environmental protection. In the context of a procedural perspective, access to information, participation in public affairs and access to justice and other such rights are essential in establishing governance structures that facilitate society to adopt fair decision-making processes on matters related to the environment. The environmental aspects of some of the protected rights are highlighted in the substantive part;

(iii)integrating IHR and the environment under the SD, thereby underlining the need to treat societal objectives in an integrated manner with EES justice factoring in the concept of SD.

The above-discussed three approaches have profoundly influenced global vision, policymaking, development of credible jurisprudence relating to IHR and the environment and the debate over the recognition and acceptance of a new IHR for a healthy environment (UN General Assembly, 2011a; Boer and Boyle, 2014; Kaltenborn, Krajewski and Kuhn, 2020). The three approaches cited above are compatible, capable of coexisting and do not necessarily exclude one another.

Another school of thought (Akyuz, 2021) is that IHR and the environment have CER in two ways (i) the environment is seen as a pre-condition of the realisation of IHR; (ii) IHR can be an effective tool for the attainment of environmental safety. These two relations are brought together under the aegis of the environment.

The recognition of the close relationship between IHR and the environment has largely taken two forms: (a) the adoption of a new explicit right to the environment characterised as healthy, safe, satisfactory, or sustainable; and (b) heightened attention to the relationship to the environment of already recognised rights, such as the right to life and health (UN Human Rights Council, 2013).

The second core issue mentioned above, namely examining whether the international community recognises a new IHR for a healthy environment, relates to consideration for the recognition of an IHR for a healthy environment and divergent views are seen in its recognition mode and legal implementation mode (UN General Assembly, 2011a).

Based on the theoretical framework principles of CER between HR-T&I and E-SDG, the two arguments can be cited to characterise the CER between HR-T&I and ET-SDG (Shelton, 2006); (i) legally binding and nonbinding HR-T&I incorporates IHR principles to include an environmental dimension when environmental degradation averts complete fulfilment of the guaranteed rights; and (ii) legally binding and nonbinding HR-T&I demonstrate a new substantive IHR to a safe and healthy environment.

In the first argument, HR-T&I seeks to ensure that environmental conditions do not deteriorate to a stage wherein the substantive right to life, health, culture, family, private life, and other IHR is seriously impaired. By focusing on the impact of environmental damage on existing IHR, this argument is used to deal with the most serious cases of real or imminent pollution. The core advantage of this argument is that existing IHR complaint procedures may be deployed against those States having environmental protection levels below a cut-off stage that must be maintained to achieve any of the guaranteed IHR. Using existing IHR law has limitations as it cannot be readily deployed for resolving threats in certain peculiar situations where other species or ecological processes have no direct linkage with human well-being. The second argument is to frame a new IHR to an environment that is not well-defined entirely in an anthropocentric manner; a safe environment for humans, ecologically balanced and sustainable in the true sense.

The theoretical approach led to developing and adopting several HR-T&I that reflect the growing relationship between IHR and the environment. Several HR-T&I concluded since the Stockholm Conference have included explicit references to the environment or recognised a right to a healthy environment. The core HR-T&I have addressed the environmental dimensions of the rights protected under their respective treaties differently in the form of General Comments, decisions concerning individual petitions and concluding observations. IHR mechanisms have also clarified the linkages between IHR and the environment. Many sources, including the HRC, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the special rapporteurs, have identified environmental threats to the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (UN Human Rights Council, 2013).

Typically an analytical study on the subject needs to examine the key components of the CER between core HR-T&I and E-SDG, with emphasis on (i) the conceptual relationship between core HR-T&I principles and E-SDG; (ii) environmental threats to core HR-T&I principles; (iii) mutual reinforcement of E-SDG and core HR-T&I protection; and (iv) extraterritorial dimensions of core HR-T&I and E-SDG (UN General Assembly, 2011a). The study presents the key components of the CER between various core HR-T&I and E-SDG, as enumerated earlier.

3. TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF CORE HR-T&I IN THE CONTEXT OF E-SDG

3.1. Approach

The IHR provides direction for the deployment of the 2030 Agenda for SD, and similarly, the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs can contribute significantly to achieving the IHR. A textual analysis of the core HR-T&I is also provided, focusing on possibilities for CER with E-SDG. The substantive rights, negative and restrictive obligations for States to avoid initiating activities that may hinder the IHR, States' positive and proactive obligations to protect and comply with the IHR, procedural obligations for ensuring access to information and performing environmental and social impact assessments, the fundamental right to participate in government and public affairs, public participation in environmental decision-making and remedy mechanisms for IHR violations are analysed. The section gives various provisions of legally binding and nonbinding core HR-T&I in the context of E-SDG, with a qualifying statement that the HR-T&I list is not comprehensive or chronological.

3.2. UDHR

The UDHR defines all peoples as free and equal in rights and dignity, without distinction of any kind. Equality before the law, right to equal protection without discrimination, freedom of opinion and expression, and right to safe and healthy working conditions are inherent to these rights. It is essential to appreciate the fact the IHR should encompass the right to a safe, clean, healthy, and sustainable environment. This is enabled through a right of access for everybody for the identified basic resources like clean air-water and sustainable clean energy, being integral to the full enjoyment of a wide range of IHR, including but not limited to the rights to life, and health, food, water and sanitation (Gordon Brown, 2016). From the UDHR onward, HR-T&I have established that States should provide an “effective remedy” for violations of their protected IHR.

The important articles of UDHR (UN General Assembly, 1948) in the context of CER with E-SDG would include:

Art. 3: “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.”

Art. 8: “Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted..”.

Art. 19: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information…” The right to information is also critical to the exercise of other rights, including rights of participation and are “both rights in themselves and essential tools for the exercise of other rights, such as the right to life, the right to the highest attainable standard of health, the right to adequate housing and others” (UN Human Rights Council, 2008, 2013). The IHR of all persons to seek, receive and impart information is provided for, and they include information on environmental matters. The IHR obligations relating to the environment include a general obligation of non-discrimination in their application, particularly the right to equal protection under the law, which is protected by the UDHR (UN Human Rights Council, 2013).

Art. 21.1: “Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country…”

Art. 25.1: “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security ……”. The right shall also include a clean environment.

Art. 26.2: “Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms…..”

Art. 27.1: “Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.”

Art. 27.2: “Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests ….”

Art. 28: “Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms ……”

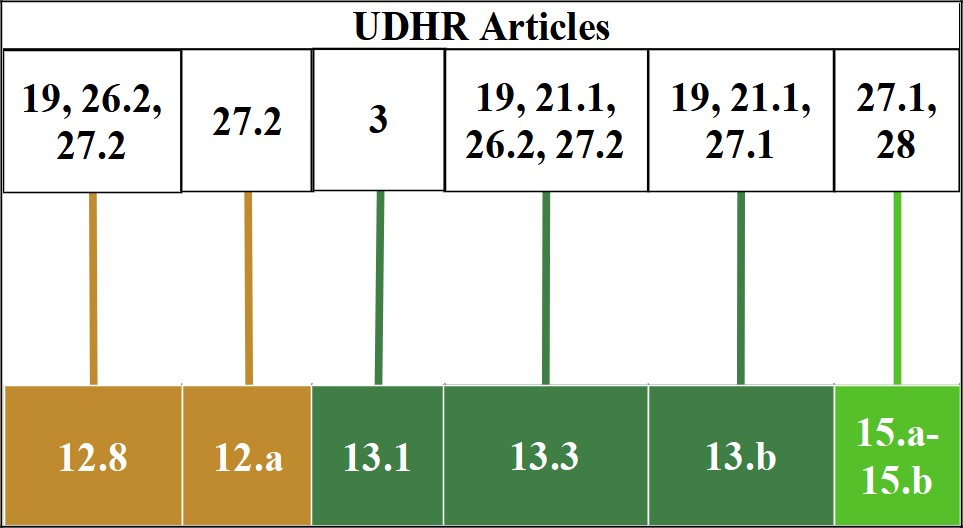

Based on the above textual analysis, Figure 2 depicts the provisions of UDHR and CER with E-SDG 12-15.

Figure 2: Provisions of UDHR and CER with E-SDG 12-15

3.3. ICERD

The proscription against racial discrimination is fundamental and intensely engrained in international law. ICERD is one of the core HR-T&I against racial discrimination in different areas of private and public life. States Parties have stated that racial discrimination should be prohibited and have complied with the Convention's provisions.

The important articles of ICERD (UN General Assembly, 1965) in the context of CER with E-SDG would include:

Art. 2.1: “States Parties condemn racial discrimination and undertake to pursue by all appropriate means and without delay a policy of eliminating racial discrimination in all its forms….”

Art. 5: “In compliance with the fundamental obligations laid down in article 2 of this Convention, States Parties undertake to prohibit and to eliminate racial discrimination in all its forms and to guarantee the right of everyone, without distinction……:”

Art. 5(a): “The right to equal treatment before the tribunals and all other organs administering justice.”

Art. 5(c): “Political rights, in particular the right to participate in the elections to vote and to stand for election on the basis of universal and equal suffrage, to take part in the Government as well as in the conduct of public affairs at any level and to have equal access to public service.”

Art. 5(e): “Economic, social and cultural rights, in particular:”

Art. 5(e)(i): “The rights to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work, to protection against unemployment, to equal pay for equal work, to just and favourable remuneration.”

Art. 5(e)(vi): “The right to public health, medical care, social security and social services.”

Based on the above textual analysis, Figure 3 depicts the provisions of ICERD and CER with E-SDG 12-15

Figure 3: Provisions of ICERD and CER with E-SDG 12-15

3.4. ICESCR

ICESCR recognises a wide range of economic, social, and cultural rights; the right to health, education, work, social security, and culture without discrimination as to ethnicity, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinions, national or social origin, economic status, birth or other status. ICESCR recognises, in particular, the right of every individual to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; the right of every individual to a decent standard of living for oneself and one’s family, including adequate food, clothing, and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions. It also recognises the right of all persons to benefit from fair working conditions, which, in particular, ensure safe and healthy working conditions. States Parties to the Covenant must make efforts to guarantee the full realisation of the rights referred to in the Covenant, including those required to (i) reduce stillbirth and infant mortality and provide for the healthy development of children; (ii) improve all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene; (iii) prevent, treat, and control epidemic, endemic, occupational, and other diseases; and (iv) create conditions that would assure medical service and medical attention to all in the event of sickness.

The important articles on ICESCR (UN General Assembly, 1966b) in the context of CER with E-SDG include:

Art. 1.2: “All peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources without prejudice to any obligations arising out of international economic co-operation, based upon the principle of mutual benefit and international law. In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.”

Art. 2.1: “Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realisation of the rights recognised in the present Covenant….”

Art. 2.2: “The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to guarantee that the rights enunciated in the present Covenant will be exercised without discrimination of any kind ….”. The responsibilities of States to proscribe discernment and ensure equal and effective protection against discrimination apply to the equal enjoyment of IHR relating to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment.

Art. 3: “The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to ensure the equal right of men and women to the enjoyment of all economic, social and cultural rights set forth in the present Covenant.”

Art. 11.1: “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognise the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions…*.”

Art. 11.2; “The States Parties to the present Covenant, recognising the fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger, shall take, individually and through international co-operation, the measures, including specific programmes, which are needed:”

Art. 11.2(a): “To improve methods of production, conservation and distribution of food by making full use of technical and scientific knowledge, by disseminating knowledge of the principles of nutrition and by developing or reforming agrarian systems in such a way as to achieve the most efficient development and utilisation of natural resources.”

Art. 11.2(b): “Taking into account the problems of both food-importing and food-exporting countries, to ensure an equitable distribution of world food supplies in relation to need.”

Art. 12.1: “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognise the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.”

Art. 12.2: “The steps to be taken by the States Parties to the present Covenant to achieve the full realisation of this right shall include those necessary for:”

Art. 12.2(b): “ The improvement of all aspects of environmental and industrial hygiene.”

Art. 12.1 and 12.2: The right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health implies the enjoyment of, and equal access to, appropriate health care and, more broadly, to goods, services and conditions which enable a person to live a healthy life. Underlying determinants of health include adequate food and nutrition, housing, safe drinking water and adequate sanitation, and a healthy environment (UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), 1999)

Art. 13.1: “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognise the right of everyone to education. They agree that education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity and shall strengthen the respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms…..”

Art. 15.1: “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognise the right of everyone:”

Art. 15.1(b): “To enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications.”

Art. 15.1(c): “To benefit from the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.”

Art. 15.2: “The steps to be taken by the States Parties to the present Covenant to achieve the full realisation of this right shall include those necessary for the conservation, the development and the diffusion of science and culture.”

Art. 15.3: “The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to respect the freedom indispensable for scientific research and creative activity.”

Art. 15.4: “The States Parties to the present Covenant recognise the benefits to be derived from the encouragement and development of international contacts and co-operation in the scientific and cultural fields.”

Based on the above textual analysis, Figure 4 depicts the provisions of ICERSCR and CER with E-SDG 12-15.

Figure 4: Provisions of ICESCR and CER with E-SDG 12-15

3.5. ICCPR

According to the ICCPR, all human beings have the inherent right to life; that no person be arbitrarily deprived of his or her life. Each State Party to the Covenant must respect all persons on its territory and subject to its jurisdiction without distinction of any nature whatsoever. Ethnic origin, colour, gender, language, religion, political or other ideology, national or social origin, economic status and situation, birth or other status In matters of equality, it recognises that everyone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection before the law, without discrimination. It also establishes that all peoples have the right to self-determination, under which they freely determine their political status and continue their economic, social and cultural development. All peoples are eligible to dispose of their natural wealth and resources, without restrictions, for their ends, without prejudice to any obligations or restrictions arising out of economic co-operation, evolved on mutual benefit and international law. Under no circumstances is it possible to deprive a people of their means of subsistence.

The important articles of ICCPR (UN General Assembly, 1966a) in the context of CER with E-SDG would include:

Art. 1.2: “All peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources without prejudice to any obligations arising out of international economic co-operation, based upon the principle of mutual benefit and international law. In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence.”

Art. 2.1: “Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognised in the present Covenant, without distinction of any kind, such as …”

Art. 2.3(a): “Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to ensure that any person whose rights or freedoms as herein recognised are violated shall have an effective remedy, notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity.”

Art. 6: The right to life is explicitly protected. The HRC has adopted the right to life as the “supreme right”, “basic to all IHR”, and it is a right from which no derogation is permitted even in times of public emergency (UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), 1982; UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), 2000). Moreover, the Committee has clarified that the IHR to life imposes responsibilities on States to proactively adopt positive measures for its protection, including taking adequate measures to decrease infant mortality, malnutrition and epidemics (UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), 1982). In General Comment No. 36 (UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), 2019), the Committee stated, among other things, that the duty of States to protect life: “implies that States Parties should take appropriate measures to address the general conditions in society that may give rise to direct threats to life or prevent individuals from enjoying their right to life with dignity,” which may include “degradation of the environment.” (UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), 2019).

Art. 6.1: “Every human being has the inherent right to life. This right shall be protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.”

Art. 16: “Everyone shall have the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.”

Art. 19.1: “Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.”

Art. 19.2: “Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.” The right to information is also critical to the exercise of other rights, including rights of participation. The rights to information and participation are “both rights in themselves and essential tools for the exercise of other rights, such as the right to life, the right to the highest attainable standard of health, the right to adequate housing and others” (UN General Assembly, 1966a; UN Human Rights Council, 2008, 2013). The IHR of all persons to seek, receive and impart information include information on environmental matters.

Art. 25(a): “To take part in the conduct of public affairs…”

Art. 25(b): “To vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret ballot, guaranteeing the free expression of the will of the electors.”

Based on the above textual analysis, Figure 5 depicts the provisions of ICCPR and CER with E-SDG 12-15.

Figure 5: Provisions of ICCPR and CER with E-SDG 12-15

3.6. CEDAW

CEDAW condemns discrimination against women in all its forms and recognises the rights and obligations of States in the promotion and protection of women’s rights. States should eradicate any act or practice of discrimination against women and, in particular, ensure that public authorities and institutions take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the health care field to ensure an equal basis between men and women, access to health care services. CEDAW also recognises the right of all women to safe working conditions. It further establishes the obligation of States Parties to take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in rural areas to ensure an equal basis between men and women, among other things, include, including participation in rural development and reaping the benefit of such development, ensuring their right to enjoy adequate living conditions, particularly in the areas of housing, sanitation, electricity and water supply, transport, and communications. CEDAW provides a more detailed framework for protecting women's rights and ensuring they have a voice in public decisions.

The important articles on CEDAW (UN General Assembly, 1979) in the context of CER with E-SDG include:

Art. 2(b): “States Parties condemn discrimination against women in all its forms, agree to pursue by all appropriate means and without delay, a policy of eliminating discrimination against women and, to this end, undertake to adopt appropriate legislative and other measures, including sanctions where appropriate, prohibiting all discrimination against women.” The committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women has identified many types of environmental harm, including natural disasters, climate change, nuclear contamination and water pollution, that can adversely affect IHR protected under the CEDAW (UN General Assembly, 1979; UN Human Rights Council, 2013).

Art. 7(a): “To vote in all elections and public referenda and to be eligible for election to all publicly elected bodies.”

Art. 7(b): “To participate in the formulation of government policy and the implementation thereof and to hold public office and perform all public functions at all levels of government.”

Art. 7(c): “To participate in non-governmental organisations and associations concerned with the public and political life of the country.”

Art. 10(c): “The elimination of any stereotyped concept of the roles of men and women at all levels and in all forms of education…..”

Art. 10(h): “Access to specific educational information to help to ensure the health and well-being of families, including information and advice on family planning.”

Art. 11.1(a): “The right to work as an inalienable right of all human beings.”

Art. 11.1(b): “The right to the same employment opportunities..”

Art. 11.1(c): “The right to free choice of profession and employment, the right to promotion, job security and all benefits and conditions of service and the right to receive vocational training and retraining….”

Art. 11.1(d): “The right to equal remuneration, including benefits, and to equal treatment in respect of work of equal value, as well as equality of treatment…”

Art. 11.1(f): “The right to protection of health and to safety in working conditions….”

Art. 11.2: “States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the field of employment….”

Art. 14.2: “States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in rural areas…..”

Art. 14.2(g): “To have access to agricultural credit and loans, marketing facilities, appropriate technology and equal treatment in land and agrarian reform ……”

Art. 14.2(h): “To enjoy adequate living conditions, particularly in relation to housing, sanitation, electricity and water supply, transport and communications.”

Based on the above textual analysis, Figure 6 depicts the provisions of CEDAW and CER with E-SDG 12-15.

Figure 6: Provisions of CEDAW and CER with E-SDG 12-15

3.7. CRC

CRC recognises children's right to life, physical, mental, and moral integrity and health, the right to safe and healthy working conditions for adolescents, and their right to a healthy environment. It further guarantees the right of children and adolescents to rest and leisure and equal opportunities for cultural, artistic, and recreational activities. CRC also recognises the right of children to enjoy the highest attainable health standard and services for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health. To this end, States Parties must pursue full implementation of this IHR and, in particular, take appropriate steps to combat disease and malnutrition, including within the framework of primary health care, among other aspects, the application of readily available technology and the provision of adequate nutritious foods and clean drinking-water, dovetailing the dangers and risks of environmental pollution. Further, the Convention provides that children’s education should be directed, among other things, to instil in them respect for the natural environment. The Committee on the Rights of the Child (UN General Assembly, 1989; UN Human Rights Council, 2013) recognised and addressed the issue of considering environmental hazards as barriers to attaining the right to health and other rights.

The important articles of CRC (UN General Assembly, 1989; Wernham, 2016) in the context of CER with E-SDG would include:

Preamble: “Bearing in mind that the peoples of the UN have, in the Charter, reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights and in the dignity and worth of the human person, and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom.”

“Recognising that, in all countries in the world, there are children living in exceptionally difficult conditions, and that such children need special consideration.”

“Recognising the importance of international cooperation for improving the living conditions of children in every country, in particular in the developing countries.…”

Art. 2.1: “States Parties shall respect and ensure the rights set forth in the present Convention to each child within their jurisdiction without discrimination of any kind…”

Art. 2.2: “States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure that the child is protected against all forms of discrimination or punishment on the basis of …”

Art. 4: “States Parties shall undertake all appropriate legislative, administrative, and other measures for the implementation of the rights recognised in the present Convention…”

Art. 6.1: “States Parties recognise that every child has the inherent right to life.”

Art. 6.2: “States Parties shall ensure to the maximum extent possible the survival and development of the child.” The right to life is explicitly protected under CRC and links it to the obligation of States for the survival and development of the child; accordingly, General Comment No. 7 (2006) (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), 2006) suggest that the survival and development of the child need to be implemented in a holistic manner, “through the enforcement of all the other provisions of the Convention, including rights to health, adequate nutrition, social security, an adequate standard of living, a healthy and safe environment …”.

Art. 12.1: “States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child….”

Art. 13.1: “The child shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers ….”

Art. 15.1: “States Parties recognise the rights of the child to freedom of association and to freedom of peaceful assembly.”

Art. 17: “States Parties recognise the important function performed by the mass media and shall ensure that the child has access to information and material from a diversity of national and international sources ….:”

Art. 23.1: “States Parties recognise that a mentally or physically disabled child should enjoy a full and decent life, in conditions, which ensure dignity, promote self-reliance and facilitate the child's active participation in the community.”

Art. 24.1 “States Parties recognise the right of the child to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health and to facilities for the treatment of illness and rehabilitation of health.”

Art. 24.2: “States Parties shall pursue full implementation of this right and, in particular, shall take appropriate measures:”

Art. 24.2(c): “To combat disease and malnutrition, including within the framework of primary health care, through, inter alia, the application of readily available technology and through the provision of adequate nutritious foods and clean drinking water, taking into consideration the dangers and risks of environmental pollution.”

Art. 24.2 and 24.2(c): The States Parties shall take appropriate measures to combat disease and malnutrition with due consideration to the dangers and risks of environmental pollution. CRC outlines a variety of additional requirements that are relevant to the protection of children in the context of climate change.

Art. 27.1: “States Parties recognise the right of every child to a standard of living adequate for the child's physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development.”

Art. 27.3: “States Parties, in accordance with national conditions and within their means, shall take appropriate measures to assist parents and others responsible for the child to implement this right and shall, in case of need, provide material assistance and support programmes, particularly with regard to nutrition, clothing and housing.”

Art. 28.3: ”States Parties shall promote and encourage international co-operation in matters relating to education…..”

Art. 29.1(a): “States Parties agree that the education of the child shall be directed to the development of the child’s personality, talents and mental and physical abilities to their fullest potential;.”

Art. 29.1(e): “The development of respect for the natural environment.” States have acknowledged that the education of the child needs to focus, among other things, on the development of respect for IHR and the natural environment.

Art. 30: “In those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities or persons of indigenous origin exist, a child belonging to such a minority or who is indigenous shall not be denied the right..”

Art. 37(c): “Every child deprived of liberty shall be treated with humanity and respect for the inherent dignity of the human person….”

Children must be recognised as active participants and custodians of natural resources in promoting and protecting a safe and healthy environment (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), 2003). Benefiting from near-universal ratification, the CRC obliges States to take measures to ensure the realisation of all rights under the Convention for all children under their jurisdiction. The CRC also obliges States to take measures to protect children's right to life, survival and development, including addressing pollution and environmental degradation.

Significant divergent views are witnessed in analysing provisions of the CRC(Wernham, 2016; The Danish Institute of Human Rights, 2017). Some reports consider that all of the SDGs are relevant for children and not only those specifically referring to children, and the distinction between child-and adult-specific SDGs is not rigid (Wernham, 2016). Some authors(The Danish Institute of Human Rights, 2017) prefer to cite no indirect reference or only a few articles, while others adopt a substantial citation level (Wernham, 2016). The reason cited for such deliberate broad interpretation can be explained with an example of SDG target 12.4: “By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks, and significantly reduce their release to air, water and soil in order to minimise their adverse impacts on human health and the environment” (UN General Assembly, 2015); responds to no rights directly relating to the child; on the other hand a broad interpretation include Convention Art. 24.2 (c) taking into consideration the dangers and risks of environmental pollution of many children put at risk living near industrial establishments, and similar views of broad interpretation are found in the literature (Wernham, 2016).

Based on the above textual analysis, Figure 7 depicts the provisions of CRC and CER with E-SDG 12-15.

Figure 7: Provisions of CRC and CER with E-SDG 12-15

3.8. ICRMW

ICRMW aims to protect migrant workers and their families from exploitation and violations of the IHR, whatever their migratory status. ICRMW reaffirms the fundamental rights embodied in the UDHR and other HR-T&I. ICRMW defines civil and political rights related to the specific situation of migrant workers and includes provisions on violations of migration legislation and prohibitions. It also defines the economic, social and cultural rights of migrant workers concerning their particular situation, such as the right to basic health care or the right to education for migrant workers' children.

The articles of ICRMW (UN General Assembly, 1990) in the context of CER with ET-SDG would include:

Art. 7 “States Parties undertake, in accordance with the international instruments concerning human rights, to respect and to ensure to all migrant workers and members of their families within their territory or subject to their jurisdiction the rights provided for in the present Convention without distinction of any kind such as…..”

Art. 9: “The right to life of migrant workers and members of their families shall be protected by law.”

Art. 41.1: “Migrant workers and members of their families shall have the right to participate in public affairs of their State of origin and to vote and to be elected…”

Art. 41.2: “The States concerned shall, as appropriate and in accordance with their legislation, facilitate the exercise of these rights.”

Art. 42.1: “States Parties shall consider the establishment of procedures or institutions through which account may be taken, both in States of origin and in States of employment, of special needs, aspirations and obligations of migrant workers and members of their families and shall envisage, as appropriate, the possibility for migrant workers and members of their families to have their freely chosen representatives in those institutions.”

Art. 42.2: “States of employment shall facilitate, in accordance with their national legislation, the consultation or participation of migrant workers and members of their families in decisions concerning the life and administration of local communities.”

Art. 42.3: “Migrant workers may enjoy political rights in the State of employment if that State, in the exercise of its sovereignty, grants them such rights.”

Based on the above textual analysis, Figure 8 depicts the provisions of ICRMW and CER with E-SDG 12-15.

Figure 8: Provisions of ICRMW and CER with E-SDG 12-15

3.9. CRPD

The objective of the CRPD is to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all IHR and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity. CRPD, having an explicit dimension of social development, gives a new dimension to viewing disabled persons, people with rights who are equipped to claim those rights and make decisions pertaining to their lives not only based on their free and informed consent but also on being active members of society. The CRPD generally classifies persons with disabilities and reiterates that all persons with various disabilities must enjoy all fundamental freedoms and the IHR. It elucidates and qualifies (i) how all groups of IHR apply to persons with disabilities; (ii) recognises areas where adaptations need to be made for persons with disabilities to efficiently exercise their IHR; (iii) areas where their IHR have been desecrated; and (iv)where protection of IHR must be reinforced.

The important articles of CRPD (UN General Assembly, 2006) in the context of CER with E-SDG would include:

Art. 4.3: “In the development and implementation of legislation and policies to implement the present Convention, and in other decision-making processes concerning issues relating to persons with disabilities, States Parties shall closely consult with and actively involve persons with disabilities, including children with disabilities….”

Art. 5.1 “States Parties recognise that all persons are equal before and under the law and are

entitled without any discrimination to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law.”

Art. 5.2 “States Parties shall prohibit all discrimination on the basis of disability and guarantee to

persons with disabilities equal and effective legal protection…..”

Art. 9.2(g): “Promote access for persons with disabilities to new information and communications technologies and systems, including the Internet.”

Art. 9.2(h): “Promote the design, development, production and distribution of accessible information and communications technologies and systems at an early stage so that these technologies and systems become accessible at minimum cost.”

Art. 10: “States Parties reaffirm that every human being has the inherent right to life and shall take all necessary measures to ensure its effective enjoyment by persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others.”

Art. 11: “States Parties shall take, in accordance with their obligations under international law, including international humanitarian law and international human rights law, all necessary measures to ensure the protection and safety of persons with disabilities in situations of risk, including situations of armed conflict, humanitarian emergencies and the occurrence of natural disasters.”

Art. 21(a): “Providing information intended for the general public to persons with disabilities in accessible formats and technologies….”

Art. 21(b): “Accepting and facilitating the use of sign languages, Braille, augmentative and alternative communication, and all other accessible means, modes and formats of communication of their choice by persons with disabilities in official interactions.”

Art. 21(c): “Urging private entities that provide services to the general public, including through the Internet, to provide information and services in accessible and usable formats for persons with disabilities.”

Art. 21(d): “Encouraging the mass media, including providers of information through the Internet, to make their services accessible to persons with disabilities.”

Art. 21(e): “Recognising and promoting the use of sign languages.”

Art. 24.3(a): “Facilitating the learning of Braille, alternative script, augmentative and alternative modes, means and formats of communication…”

Art. 24.3(b): “Facilitating the learning of sign language and the promotion of the linguistic identity of the deaf community.”

Based on the above textual analysis, Figure 9 depicts the provisions of CRPD and CER with E-SDG 12-15.

Figure 9: Provisions of CRPD and CER with E-SDG 12-15

4. ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION ON CER OF CORE HR-T&I WITH E-SDG

4.1. Approach

As detailed in above considerations, most of listed core HR-T&I (i) contain substantive rights, such as IHR to life, health, and an adequate standard of living, supported by a set of (a) negative and restrictive obligations for States in order to avoid initiating activities that may hinder the IHR or other actions of this type nullifying their obligation to comply with the IHR and (b) States' positive and proactive obligations to protect and comply with the IHR; (ii) procedural obligations, that recognise IHR of all persons “to seek, receive and impart information” for ensuring access to information and performing environmental and social impact assessments; (iii) acknowledging the fundamental right of every individual to take part in the government of their country and in the conduct of public affairs; (iv) establishing and demonstrating that governments have an obligation to facilitate public participation in environmental decision-making in order to protect IHR against environmental harm; and (v) conceding that States should provide an “effective remedy” for IHR violations. The responsibilities of States to proscribe discrimination and to ensure equal and effective protection against discrimination also apply to the equal enjoyment of IHR relating to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment. The responsibilities of States to deliver access to judicial and other procedures for effective remedies for violations of IHR also encompass remedies for violations of IHR pertinent to environmental issues (Knox, J.H. and Morgera, 2022). The baseline IHR of every individual to participate in the government of their country, including in the conduct of public affairs, is recognised. This right also includes participation in decision-making related to the environment (UN General Assembly, 1948, 1966a; UN Human Rights Council, 2013). To safeguard against environmental harm and for taking necessary measures for the full attainment of IHR that be contingent on the environment, States need to create a robust mechanism for the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment, including establishing, maintaining and enforcing effective legal and institutional frameworks (UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), 2002; UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), 2013; UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), 2019; Knox, J.H. and Morgera, 2022). The obligations of States to cooperate to achieve universal respect for and observance of IHR require them to work together to address transboundary and global threats to IHR.

The reinforcing nature of core HR-T&I with ET-SDG 12-15 is analysed. Sections 4.2 to 4.5 give a CER nature of core HR-T&I with ET-SDG 12-15, respectively, in a qualitative manner. The actual text of ET-SDG 12-15 is analysed in more detail and is subjected to textual analysis, in which the language of ET-SDG 12-15 is compared with authoritative codifications of the various core HR-T&I. with a qualifying statement that the HR-T&I list is not comprehensive or chronological.

4.2. Analysis of CER of core HR-T&I with E-SDG 12

Eight substantive targets of E-SDG 12 and three targets on means of implementation focus on responsible consumption and production, encompassing a wide range of themes that could enable the decoupling of inclusive economic growth from natural resource use and material consumption and chemicals and waste valorisation. Decoupling is imperative due to the rapid depletion of natural resources and EES considerations. Decoupling and other initiatives on E-SDG 12 is a proactive initiative towards migrating to a sustainable business model and circular economy, triple bottom line and Environment, Social, Governance (ESG) reporting (B. Suresh, Erinjery Joseph James and Jegathambal, 2016; B. Suresh, 2017; B.Suresh, 2018; Asian Development Bank, 2019).

The report of the Independent Expert (UN Human Rights Council, 2013) on the issue of IHR obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment mapped IHR obligations relating to the environment global IHR treaties by analysing the text of the agreements of core HR-T&I. In addition to the text of the agreements, the reports examined relevant interpretations of the treaty bodies via the general comments, country reports and views on communications.

The IHR to sustainable consumption and production patterns is a relatively new addition to the catalogue of IHR. While no direct or implicit CER with ICERD and ICRMW could be cited, explicit and implicit CER with E-SDG 12 can be found in other core HR-T&I.

UDHR has a low-level CER on this subject, reflecting remote CER with ET-SDG 12.8, 12(a).

ICESCR includes text relating to environmental and industrial hygiene matters in the workplace. Coining social elements of good health, like environmental safety and awareness, can help in controlling and preventing infectious diseases. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has adopted various General Comments relevant to the environment and SD, notably General Comments 14 and 15, which interpret Art. 11 and 12 of the ICESCR to include access to sufficient, safe, and affordable water for domestic uses and sanitation (UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), 2000, 2002). They also cover the prevention and reduction of exposure to harmful substances, including radiation and chemicals, or other detrimental environmental conditions that directly or indirectly impact human health (Boer and Boyle, 2014). General Comment No. 14 elaborates on the right to health, and its underlying determinants, including a clean environment and specifically, mention that State Parties proclaim national policies towards “reducing and eliminating pollution of air, water and soil, including pollution by heavy metals such as lead from gasoline” (UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), 2000). In General Comment No. 12 (UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), 1999), the Committee has also clarified the linkages between environmental safety and the realisation of the right to adequate food and such rights require the State party to adopt “appropriate EES policies”. These policies are essential for ensuring food is “free from adverse substances” contamination through inadequate environmental hygiene. It is also important to note that climate change, the productivity of land, and other natural resources were also mentioned in General Comment No. 12 and that these elements are inextricably linked to the environmental health of soils and water. In General Comment No. 15, the Committee explicitly linked the right to water to environmental concerns, observing that adequate water supplies are those which are “free from micro-organisms, chemical substances and radiological hazards” as well as having “an acceptable colour, odour and taste for each personal and domestic use” (UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), 2002). Thus, enjoyment of the right to adequate water depends on the environmental purity of the water. Thus satisfying the standards of the ICESCR cannot be done without adhering to responsible consumption and sustainable production practices. Comparatively, ICESCR has several reasonable levels of explicit and implicit CER with E-SDG 12 with Art. 12.1, 12.2(b) having a direct CER with ET-SDG 12.4, and Art. 11, 11.2(a)-11.2(b) with ET-SDG 12.3.

Similar to UDHR, no direct CER could be cited in ICCPR. Further, ICCPR has a minimum CER on this subject, reflecting remote reference to ET-SDG 12.2, 12.8 (The Danish Institute of Human Rights, 2017). CEDAW has the implicit nature of CER confined to one target, i.e. ET-SDG 12.8 (The Danish Institute of Human Rights, 2017). While no direct or indirect CER could be cited to CRC with E-SDG 12 in certain reports (The Danish Institute of Human Rights, 2017), few reports make a substantial level of citations, both direct and by deliberately adopting a broad interpretation of the CRC. Direct CER with CRC could be cited with Art. 29.1(e) (ET-SDG 12.2), and Art. 24.2(c) (ET-SDG 12.4). The rest of the CER with CRC is only implicit in nature with broad interpretation, and accordingly, CRC exhibit the moderate level of CER with E-SDG 12 (Wernham, 2016).

CRPD has the implicit nature of CER confined to one target, i.e. ET-SDG 12.8 (The Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2008). While the CEDAW approach is to reduce the traditional burden on the women operating in an unhygienic environment with restricted technologies, CRC reference is more on ensuring quality life for children from health considerations, and CRPD refers to ensuring quality life for persons with disabilities.

With low CER of core HR-T&I with E-SDG 12 and implicit references, some targets of E-SDG 12 adopt a language that explicitly expresses IHR principles. The CER between core HR-T&I and E-SDG 12 reflect (i) the conceptual relationship between core HR-T&I principles and E-SDG 12 (ET-SDG 12.3, 12.5, 12.7, 12.8, 12(b)); (ii) E-SDG 12 threats to core HR-T&I principles (ET-SDG 12.4); (iii) mutual reinforcement of E-SDG 12 and core HR-T&I protection (ET-SDG 12.2, 12.6, 12(c)); and (iv) extraterritorial dimensions of core HR-T&I and E-SDG 12 (ET-SDG 12.1, 12(a)).

Based on the above textual analysis, Figure 10 summarises the CER of HR-T&I with ET-SDG 12 qualitatively.

Figure 10: Summary of CER of legally binding and nonbinding core HR-T&I with E-SDG 12 in a qualitative manner

4.3. Analysis of CER of core HR-T&I with E-SDG 13

E-SDG 13 on climate action is a significant issue and undoubtedly a critical factor in environmentally sustainable growth in countries at risk from climate change impacts. Climate change has many interlinkages with E-SDG 12, 14, and 15. Various initiatives subsequent to the UNFCCC Paris Agreement have led to sufficient financial and other resources flowing to climate change.

The separate resolutions (7/23, 10/4, and 18/22) of the HRC identified the threat of climate change to individuals and communities and its implications on the enjoyment of IHR (Boer and Boyle, 2014). The IHR implications of climate change, including effects of mitigation and adaptation, have been studied by various authors in the context of impacts on (i) ecosystems and natural resources; (ii) physical infrastructure and human settlements; (iii) livelihoods, health, and security and concluded that even within the international goal of 2° c of global warming, these impacts will increase vividly in the near future thereby creating a serious interference with the exercise of fundamental IHR with a caution that mitigation, adaptation, and geoengineering measures can also result in IHR violation (Koivurova, Duyck and Heinämäki, 2013; IPCC, 2014; OHCHR, 2014). OHCHR report (UN Human Rights Council, 2009) depicts the impairment of the enjoyment of IHR, including obligations of States under IHR law, due to the observed and projected impacts of climate change. However, noted that “it is less obvious whether, and to what extent, such effects can be qualified as IHR violations in a strict legal sense” (UN Human Rights Council, 2009). Special rapporteurs have explained how climate change threatens a wide range of rights, including the rights to health, water and food (UN Human Rights Council, 2013).

The core HR-T&I only implicitly refer to climate change as reflected in CER with E-SDG 13. The climate change considerations are vital to the 2030 Agenda for SD. However, the CER of HR-T&I with climate change seems to be underdeveloped, even though the States are under various obligations in terms of respecting, protecting, fulfilment towards IHR principles, including obligations to mitigate domestic GHG emissions, protecting citizens against the harmful effects of climate change, and ensure that responses to climate change do not result in IHR violations (Koivurova, Duyck and Heinämäki, 2013). However, there is a growing consensus that most or all of the IHR enumerated in the UDHR constitute customary international law, and as such, they are binding on all States regardless of treaty ratification status (Louis Henkin, 1996; De Schutter, 2010; Meron, 2012; Koivurova, Duyck and Heinämäki, 2013). The linkages between climate change and IHR principles are evident and clear to the extent that they will influence the full enjoyment of IHR. The progressive acknowledgement of IHR commitments concerning the environment and climate change is seen in the review of HR-T&I. Integrated reporting under the 2030 Agenda, IHR mechanisms, and the international climate change regime can help to ensure that responses to climate change are aligned with E-SDG 13, other relevant SDGs and related IHR obligations. States need to increase their ambition with respect to climate change mitigation and adaptation and work cooperatively to ensure the protection of IHR for all citizens worldwide.

The various reports encapsulate some of the linkages and interconnections between environmental degradation arising from climate and IHR violations (Limon, 2009).

Table 1 presents, based on the A/HRC/10/61 report, the impacts of climate change on IHR and the identified CER core HR-T&I (UN Human Rights Council, 2009).

Table 1: Analysis of impacts of climate change on IHR

Effects |

IHR affected |

Reference to core HR-T&I articles |

Extreme weather events |

Right to life |

UDHR 3; ICCPR 6.1; CRC 6.1 |

Increased food insecurity and risk of hunger |

Right to adequate food, right to be free from hunger |

UDHR 25; ICERD 5(e); ICESCR 11.1, 11.2(a), 11.2(b); CEDAW 14,2(h); CRC 24(c); CRPD 25(f), 28.1 |

Increased water stress |

Right to safe drinking water |

ICESCR 11.1 and 12; CEDAW 14,2(h); CRC 24.2(c); CRPD 28.2(a) |

Stress on health status |

Right to the highest attainable standard of health |

UDHR 25.1; ICERD 5(e)(iv); ICESCR 7(b), 10 and 12; CEDAW 12 and 14.2(b); CRC 24; ICRMW 43.1(e), 45.1(c) and 70; CRPD 16.4, 22.2 and 25 |

Sea-level rise and flooding |

Right to adequate housing |

UDHR 25.1; ICERD 5(e)(iii); ICESCR 11; CEDAW 14.2; CRC 27.3; ICRMW 43.1(d); CRPD 9,1(a), 28.1 and 28.2(d) |

The provisions of Art. 12.2(b) of ICESCR comparatively have better refection to E-SDG 13. The ICESCR contains several additional rights—such as the rights to health and an adequate standard of living—which also require positive action from the State for their implementation. The ICESCR Art. 2.1 requires parties to “take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realisation of the rights recognised in the present Covenant by all appropriate means.” The UDHR and ICCPR also recognise an obligation of States to “promote universal respect for, and observance of” IHR and freedoms.

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has interpreted the ICESCR as encompassing extraterritorial obligations of this nature. Unlike the ICESCR, the ICCPR does include a jurisdictional limit. Specifically, it directs each Party “to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction,” the rights recognised therein

CEDAW is more geared towards preventing acts of overt discrimination than addressing the discriminatory effects of actions on women. As such, the CEDAW does not provide much guidance on government obligations relating to the disproportionate burden women will likely experience due to climate change.

Divergent views are witnessed in analysing provisions of CRC concerning E-SDG 13. While no direct reference could be cited to CRC with E-SDG 13, few reports make a substantial level of citations by deliberately adopting an enlarged interpretation of the E-SDG 13 and CRC as an implicit reference and accordingly, CRC exhibit a high level of CER with E-SDG 13 (Wernham, 2016).

ICERD has a low level of CER with E-SDG 13, and comparatively, ICESCR, ICRMW, and CRPD have a considerable level of implicit CER with E-SDG 13 (The Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2008; The Danish Institute of Human Rights, 2017). The rights mentioned in CRPD in Art. 11 (ET-SDG 13.1) implicitly refer to disaster risks arising from climate change.