ASSESSING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION, INDIA, VIS-À-VIS THE PARIS PRINCIPLES RELATING TO THE STATUS OF NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS INSTITUTIONS

RUCHITA KAUNDAL*

S. SHANTHAKUMAR**

Abstract: National Human Rights Institutions (NHRI) play an important role in monitoring and promoting international human rights norms in a country. However, in order to function as an effective NHRI, they must adhere to the “Paris Principles” of 1993. In 2023 the Indian NHRI prepares to renew its ’A’ grade accreditation. This offers an opportunity to assess the effectiveness of the institution in light of the aforementioned Principles. In doing so the authors address both the limitations that hinder the NHRI’s performance and the remedies. Notably, the role of “District Human Rights Courts”, in supporting the NHRI in enhancing its effectiveness.

Keywords: Human Rights, National Human Rights Institutions, Paris Principles, National Human Rights Commission India, Human Rights Courts, Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions

Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION 2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 2.1 Rationale Behind NHRIs 2.2 United Nations Campaign to Promote NHRIs 2.3 NHRIs and the Paris Principles 3. PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA 3.1 Evolution of Human Rights Protection in India 3.2 Events Contributing to the Establishment of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) 4. DOMESTIC INSTITUTIONALISATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA 4.1 An Overview - The Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 4.2 Analysing NHRC’s Compliance with the Paris Principles (Secondary Analysis) 4.2.1 Pluralistic representation within the composition of the NHRC vis -a -vis independence 4.2.2 Selection and appointment procedure of the members of the NHRC vis -a -vis structural independence 4.2.3 Financial and Administrative Autonomy 4.2.4 Broad Mandate 5. STATUTORY LIMITATIONS IN THE FUNCTIONING OF THE NHRC 5.1 Legal Constraints 5.2 Jurisdictional Constraints 6. WAYS TO ENHANCE THE CAPABILITIES OF THE NHRC 6.1 The Indian Judiciary and PHRA, 1993 6.2 Proposed Amendments to The PHRA, 1993 7. CONCLUSION

1. INTRODUCTION

Human Rights are rights intrinsic to the dignity of every individual (UDHR, 1948, art.1). To provide a conducive environment for the enjoyment of these and also to offer remedial channels to enforce the rights in times of breach rests upon the parent country of the individual (UDHR, 1948). The reason is that an individual is subject to the country’s law. At the same time, even though the government may ratify an international instrument, enjoying these rights is only possible with their practical implementation at the domestic level (NHRC, 2012, p.10).

To address this challenge, the United Nations (UN) insisted that member states establish independent human rights institutions within their domestic set-up to realise human rights practically. As a result, in 1991, the First “International Workshop on National Institutions for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights” took place in Paris (UN, 2010, p.7). The workshop’s purpose was to review the partnership between national and international institutions and determine how the alliance could be strengthened to provide better protection for human rights (Ray, 2003, p. 74). The deliberations within the workshop resulted in what came to be known as the “Paris Principles” - a set of instructions for assisting nations in establishing National Human Rights Institutions (NHRIs) (UNCHR, 1992). The draft of the principles was endorsed by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (Ibid). The United Nations General Assembly(UNGA) further voted on and adopted them as the “Principles Relating to the Status of National Institutions” (UNGA, 1993).

India was among the many countries to participate in the conference. However, divergent views on NHRI within the country initially refrained India from acting upon the “Paris Principles” (Ray, 2003, p. 83-84). The argument was that India had a well-equipped court system which protected the human rights enumerated within the national Constitution; additionally, the free press within the country was vigilant enough to keep a check as well as bring to light any incident of rights violation (Ibid). However, succumbing to international pressure in the wake of the alleged atrocities committed by the police and the armed forces in response to cross-border terrorism, the Indian government brought forth The Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 (Tiwana, 2004).

PHRA (1993) is the primary legislation for the overall protection of the human rights of the people within the country. It directly reflects India’s commitment to the 1993 “Paris Principles”. It allows for the constitution of two hierarchical institutions, namely the “National Human Rights Commission” (NHRC) at the centre (PHRA, 1993, §2) and the “State Human Rights Commissions” (SHRC) at the state level (Ibid, § 21). It further empowers the State Governments to constitute “Human Rights Courts” (HRC) at the district level (Ibid, § 30).

The present paper is divided into seven primary segments; the first segment sets the introduction and the focus to provide a framework for the assessment; the second segment of the paper gives the historical background and the rationale behind the United Nations’ (UN) campaign to set up NHRIs around the world. It further discusses the resulting document adopted by the UNGA for the promotion and protection of human rights, i.e. the “Paris Principles” and the accreditation process involved in designating an institution as an NHRI. The third segment discusses the evolution of human rights protection in India and events that led to the adoption of the PHRA. The fourth segment of the paper introduces the readers to the PHRA which establishes the NHRI for India. After doing so, the authors critically examine the NHRC’s (NHRI of India) structural compliance within the Act in light of the “Paris Principles”. The authors also look at the practical aspect of “Paris principles” through NHRC’s operations, as depicted in its last two Annual Report (s), i.e. 2018-19 and 2019-20. The reason for choosing the said Annual reports is that the reports for the year 2020-21, 2021 -22 and 2022 -2023 have not been published by the NHRC yet.

Since its inception, the NHRC has been accredited with an ‘A’ status by the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI) (Chauhan, 2018). However, in 2016, there was a shift in the decision by the GANHRI (Sahani, 2017). It refused to reaccredit India’s long-held ‘A’ grade status due to some of its compliance concerns (GANHRI, 2016, p. 24). However, with assurances made by India in amending the defects pointed out by the accreditation panel, the ’A’ status was restored to India (Thanawala, 2022). As India prepares to renew its accreditation with GANHRI under the 2023 session, it is important to examine the human rights establishment in light of the 1993 “Paris Principles” and note whether the shortcomings that posed a barrier during the 2016 review session have been resolved.

In the fifth segment of the paper, the authors point out some inherent structural limitations existing within the PHRA and list ways to overcome the roadblocks hindering the commission’s effectiveness. In doing so, the authors especially try to gather the readers’ attention on the role of the HRCs an enforcement machinery set up under Section 30 (PHRA, 1993) in increasing the effectiveness of the Commissions. The NHRC/SHRCs as they stand today are only capable of providing recommendations to the government and are devoid of any enforcement mechanism (Ibid, §18). Despite the commission’s commendatory work in the field of human rights protection, the lack of an enforcement mechanism has hampered its mandate of protecting and preventing violation of human rights. The authors suggest that the Commissions and the HRCs should work in unison to bridge this gap, making access to justice an achievable dream. The authors urge the State Governments within the Indian Union to set up SHRCs and HRCs as a first step towards the prior initiative. Finally, the last segment of the paper provides the authors concluding remarks.

2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND – NHRI

2.1 Rationale Behind Establishing NHRIs

The history of Human Rights is as old as human civilisation itself. While the expression “Human Rights” is of modern origin, traces of the idea date back to ancient and medieval times (Ghosal, 2010). The concept of “Human Rights” can be characterised as rights inherent to every human being for their overall development. Therefore, safeguarding these rights assumes priority in maintaining harmony in society.

The call for officially recognising and safeguarding these so-called “rights of man” rose towards the end of the World Wars due to the growing anti-imperialist/anti-colonialist sentiment (Rao, 1998). Subsequently, the rights acquired universal status with the foundation of the UN (Charter of the United Nations, 1945) and the adoption of the UDHR (1948). Unfortunately, the non-binding characteristic of the declaration left the rights to remain as no more than a piece of normative ideals for the states to follow (Kumar, 2003, p.260).

To amend this gap, two chief covenants, namely, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1976); and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1976), were passed by the UN. The two instruments and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) became known as the “International Bill of Human Rights” (OHCHR, no date). The universal rights of men thereby assumed the desired legal and enforceable status. However, the fact remained that mere ratification of the instruments did not automatically guarantee adequate protection by the nation-states within their domestic set-up (Hegde, 2018, p. 64). To address this challenge and make human rights a practical reality for every human being on earth, the UN started endorsing the idea of NHRIs amongst the nation-states in the early ’60s (Ray, 2003, p. 72). The establishment of these institutions was seen as a link between International Human Rights Law and Municipal Law.

2.2 UN Campaign to Promote NHRIs

The idea of establishing NHRIs was first recommended by the “Nuclear Commission” on Human Rights in its report of 21 May 1946 to the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (Miller, 1968, p. 162). As a response to that, the UN ECOSOC, by resolution no. 9 (II), invited member states to deliberate on the idea of coming up with institutions which could help in the practical realisation of human rights within each member state (Miller, 1968, p. 162).

After a 14-year reticence since the passing of the resolution, the Commission on Human Rights, in its 16th session, once again canvassed the distinctive role the NHRIs could play in protecting and promoting human rights (UNECOSOC Official Records, 1960). Therefore, the commission sought out the views of the member states, which had existing arrangements of that sought within their domestic arena (Ibid). However, much information about the institutions’ potential, nature, and operation remained to be gathered—their role within the domestic structure and their relationship with other domestic institutions needed to be further studied. Therefore, the UNGA (1977), under its resolution 32/123, recommended a worldwide seminar on National and Local Institutions for Promoting and Protecting Human Rights. The resulting seminar held in Geneva laid down the guidelines for the structure and functioning of the institutions (United Nations Division of Human Rights, 1978). This fuelled the UNs’ determination to establish NHRI(s), passing a series of resolutions. The resolutions dealt with issues such as the role of NGOs in the work of NHRIs, (UNGA, 1979), studying the various models of national institutions existing within the states (UNGA, 1981), dissemination of texts of human rights instruments in federal and local languages (Ibid), etc. As a result, the United Nations Centre for Human Rights organised its first “UN International Workshop on National Institutions for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights” in Paris in 1991 in collaboration with the French National Consultative Commission (UN, 2010, p. 7). Recalling its earlier concerns about the potential role of a NHRI, the workshop invited member states to share their experiences with NHRIs, back home – the advantages and the shortcomings and put forward their suggestions for strengthening the institutions (Ibid). The draft document prepared at the end of the workshop, was endorsed by the UN Commission on Human Rights by resolution 1992/54 (UNCHR, 1992). It was further adopted under Resolution 48/ 134 by the UNGA as the “Principles Relating to the Status of National Institutions” (UNGA, 1993). The vital role of NHRIs as actors in promoting and protecting human rights was further reaffirmed in the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action and adopted by the World Human Rights Conference OHCHR (1993). This was also the first time the NHRIs adhering to the “Paris Principles” received international recognition (UN, 2010, p. 7).

2.3 What Are NHRIs and The “Paris Principles”?

NHRIs are independent institutions within a nation’s domestic framework to protect and promote human rights (UNDP-OHCHR, 2010, p. 6).

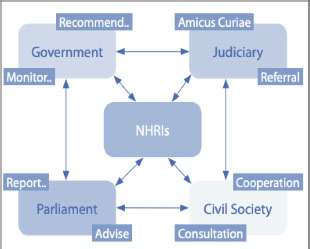

As depicted in figure no. 1 above, these extraordinary institutions, although distinct from the three organs of the state, i.e. the legislature, the executive and the judiciary, form a crucial part of the state (Ibid). They are the nexus between the organisations within the domestic system catering to the practical realisation of human rights. Their role is wider than the domestic arena. An NHRI also maintains close ties and interacts with other international actors. Allowing it to report and advise its parent state on the best human rights practices (Ibid).

Fig. 1. NHRI- Central Element of National Protection Systems.

Source: UNDP-OHCHR Toolkit for collaboration with National Human Rights Institutions, 2010.

For a human rights body to be adorned with the status of being an NHRI, it must conform to the “Paris Principles”. As mentioned earlier, the “Paris Principles” (hereinafter referred to as “the principles”) are guidelines that put forth minimum standards to function and be designated as an NHRI (UNGA, 1993).

The categorisation of these guidelines under the draft is as follows:-

a)competence and responsibilities,

b)composition and guarantees of independence and pluralism,

c)methods of operation,

d)quasi–jurisdictional competence (Ibid).

The institutions in compliance with the principles are accordingly accredited by the International Coordinating Committee of National Institutions for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, now known as the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI, 2019). The GANHRI was established by NHRIs at the second “International Workshop on National Institutions for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights” held in Tunis in 1993 (CHRC, 2017, p. 10). As a multi-lateral organisation, GANHRI’s mandate is to coordinate the work of NHRI(s) established worldwide and accredit them based on their compliance with the Principles (Ibid). The GANHRI’s Sub-Committee on Accreditation (SCA) is the body in charge of the accreditation process (Ibid). The SCA follows a unique peer review process for granting accreditation (’A’ and ’B’ status) (Ibid, p. 11). The accreditation process, in return, regulates each NHRI’s access to the UN Human Rights Council. NHRI -accredited ’A’ status has the right to vote (GANHRI, 2019, art. 24.1) and to be appointed as a member of the GANHRI bureau (Ibid, art. 31.4). The NHRI-accredited ’B’ status can only participate in the agenda meetings but not vote (Ibid, art. 24.2).

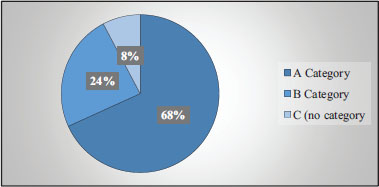

Presently there are 129 active NHRIs accredited by GANHRI worldwide (see fig. 2 below) (OHCHR, 2023).

Fig. 2. Chart of the Status of National Institutions (Accreditation status), 2023.

(Source: UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights).

As NHRIs become the missing link in the international human rights protection framework, their smooth operation is essential. The next segments of the paper thus focuses on the development of human rights law in India, ultimately resulting in the creation of India’s NHRI for achieving the dual mandate of protecting and promoting human rights.

3. PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA

3.1 Development of Human Rights Law in India

India is the world’s largest democracy, and one of the primary goals of a democratic government is to safeguard its people’s inherent human rights. As a result, the Indian government’s stance on human rights protection and prevention has been relatively high since the outset (Rubin, 1987, p.372). After years of repression under the colonial state, India as a newly found nation was determined to ensure to its people human rights, they had so long been deprived of. As a result, the Constituent Assembly (CA), formed to design a comprehensive Constitution for the country, gave special attention to people’s rights. Additionally, given the vast diversity within the Indian society, ensuring that the needs of every individual and group are effectively addressed was a monumental undertaking. Nonetheless, the CA completed the final draft of the Constitution by perfectly verbalising the lessons learnt during the struggle for independence (Kothari, 2018, p.79; Kannabiran, 1992). The citizens of the country, thereby finally adopted and gave to themselves the “Constitution of India” on the 26th January, 1950 (The Constitution, 1950). The Constitution of India includes both the civil and political rights and the economic and social rights (Ibid). However, only civil and political rights enshrined in Part III of the Constitution as “The Fundamental Rights” (FR) are rendered legally enforceable before the constitutional courts of the country (Ibid). This was due to the fact that India as a newly found state possessed a limited economic capacity and therefore ensuring these rights fully was not possible (Ranjan, 2019). The CA therefore incorporated the non-justiciable economic and social rights into Part IV of the Constitution, titled “The Directive Principles of State Policy” (DPSP) (The Constitution, 1950). The DPSP nevertheless form critical to the country’s governance and are politically enforceable (Kannabiran, 1992). In fact, the constitutional courts have in due course of time, managed to bring in some of the non-justiciable rights within the scope of the FR through a creative and liberal interpretation of Article 21 i.e. “the right to life”. (Nariman, 2013, pp. 13-26).

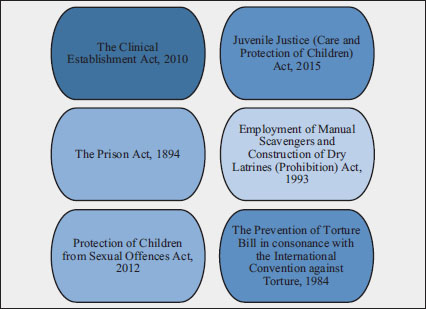

Giving citizens’ rights protection meant eradicating the social ills that pervaded Indian society. This sparked a slew of social movements across the country (Sugunakararaju, 2012). The movements centred on issues affecting the working class, the marginalised class, gender, culture, and identity, among other things (Ibid). As a result, the Indian parliament has come to enact a number of laws pertaining to the preservation and prevention of human rights within the country over time (Deol, 2011, p. 112). These laws are in conformity with the FR and the international human rights conventions that India has ratified. fig. 3 below throws a glance at some of the national legislations which have which have a bearing on the protection of human rights in the country.

Fig. 3. National Statutes Protecting Human Rights in India (Madan, 2017).

Furthermore, the Government of India established six major commissions to guide, advise, and propose solutions to issues affecting the rights of various disadvantaged groups in the country (see fig. 4 below).These commissions have helped a lot in advancing the social position of the vulnerable groups (Ibid). Four of these commissions existed prior to the establishment of the NHRC (see fig. 4 below). However, due to the limited scope of the commissions and the occurrence of some additional events, the idea of forming an NHRI dedicated solely to human rights emerged (Singh, 2018).

Fig. 4. National Commissions for Protecting the Rights of the Vulnerable in India (Deol, 2011).

3.2 Events Contributing to the Establishment of the NHRC

The proclamation of emergency period from 1975-77, is considered the darkest phase of civil rights in the country, due to the complete suspension of all the FR (Ghosh, 2017). The period post emergency thereby resulted in major agitations against the authoritarianism of the government (Ray, 2003, p. 81). Numerous human rights organisations were formed in the different parts of the country for the promotion and protection of human rights (Ibid). All this together led to the new idea of establishing an independent civil rights commission (Ibid, p.82 -83). The idea was first put forth by the Janta Party in its 1977 election manifesto (Somanathan, 2010). The need for establishing the commission again found mention by the then Chief Justice of India, Justice PN Bhagwati in 1985 and by an eminent jurist LM Singvi in 1988 (Ray, 2003, p.82). While there was this long standing demand for the creation of an independent human rights body within the country, there was also scepticism surrounding it from many (Ibid, pp.83-84). It was felt that with an independent and powerful judiciary acting as the ultimate custodian of the fundamental rights; the presence of a watchful free press and the presence of individual commissions rendered the establishment of an additional institution redundant (Ibid). The issue however assumed emergency due to a series of events in the late 1980s. The 1980s was a tumultuous period for the country, due to the spread of terrorism and insurgency in the states of Kashmir and Punjab (Sripati, 2000, p. 8; Ray, 2003, p.85). To counter these elements, the central government was compelled to extend its special counterinsurgency laws to these areas (Ibid). These laws granted the police and military forces broad powers, resulting in the emergence of state-sponsored terrorism (Ibid). As a result, incidents of arbitrary detention, torture, extrajudicial execution, and enforced disappearance of thousands by paramilitary forces started cropping up within these areas (Amnesty International, 1989). These occurrences were widely documented by the international organisations, in their publications, exposing the reality of human rights in the country (Ibid). To respond to the international pressure brought on by these instances and to defend the country’s reputation in the global community, India passed its first human rights legislation, known as the “Protection of Human Rights Act of 1993” (Jaswal and Jaswal, 1996, p. 235). The Act further depicted India’s fulfilment of its obligation under the “Paris Principles” of 1993. Thereby, creating an independent institution to investigate the country’s human rights situation (Ray, 2003, p.83).

4. DOMESTIC INSTITUTIONALISATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA

4.1 An Overview – “The Protection of Human Rights Act 1993”

The PHRA is a central legislation in India which entered into force on September 28, 1993 (PHRA, 1993, §1(3)). The Act is applicable to the whole of India and aims to offer “better protection of human rights in the country, as well as matters related to and incidental thereto” (PHRA, 1993).

To achieve the said purpose, the PHRA creates two unique forums:

1.Human Rights Commissions, i.e. The NHRC at the Centre level (PHRA, 1993, § 3) and the SHRCs at the State level (Ibid, § 21) and

2.Human Rights Courts (Ibid, § 30) - a judicial body within the cadre of criminal courts, at the district level within every state.

The Commissions are independent bodies distinct from the three government organs i.e. the legislature, the judiciary and the executive.

The NHRC

The NHRC is established by the Central Government (Ibid, § 3) and is based in New Delhi, the country’s capital.

The SHRCs

Whereas the State Government(s) have the authority to create a SHRC within their state jurisdictions (Ibid, § 21). The location of the commission’s headquarters is determined by the state government and currently, each SHRC has its headquarters in the capital city of the respective state (Ibid, § 21). The NHRC has the authority to receive complaints on violations of human rights from everywhere in the country, as opposed to the SHRC, which receive complaints from within their state’s jurisdiction.

The HRC(s)

The HRC(s) is a judicial body which belong to the cadre of district criminal court within State. Every State Government has the power to designate the district criminal court i.e. the Court of Sessions, within each district of the state as a HRC (Ibid, § 30). The HRC have the power to try the offences which arise out of a violation of human rights (Ibid, § 30).

Overall, the PHRA is divided into eight chapters consisting of a total of 43 sections which deal with the constitution, composition, powers, functions and finances relating to the commissions and the HRC.

Chapter I deals with the short title, scope, and commencement of the Act, as well as the definition clause, which defines various terms used in the Act (Ibid, § 1-2). The second chapter, titled “NHRC” is divided into 11 sections, which deal with the composition of the national commission, the appointment process of its members, the method of removal of the members, the term of office of the members, the conditions of service of the members, and the procedure to be followed by the Commission (Ibid, § 3-11). The third chapter, headed “Functions and Powers of the Commission” is divided into five sections that outline the many functions (inquire and investigate rights abuses, intervene in judicial processes, inspect jails, and conduct awareness) that the commission is obliged to fulfil as an NHRI (Ibid, § 12-16). The fourth chapter titled “Procedure” is divided into four sections which deal with the procedure to be followed by the commission when investigating complaints of human rights violations, the steps to be taken after the completion of an inquiry, and the procedure to be followed when dealing with complaints against members of the armed forces (Ibid, § 17-20). Chapter V titled “SHRC” consists of nine sections similar to those applicable to the NHRC in Chapter II of the Act, laying out the SHRC’s constitution, appointment of its members, removal of its members, term of office of the members, and conditions of service of Members (Ibid, § 21-28). It goes on to say that the SHRC’s functions and powers will be comparable to those of the NHRC, as outlined in sections I, III, and IV of the Act (Ibid, § 29). Chapter VI titled “HRC” consists of only two sections dealing with the constitution of the HRCs and the appointment of a Public Prosecutor by the respective State Government for the purposes of conducting a trial before the HRCs (Ibid, § 30-31). Lastly, Chapter VII and VIII consist of four and eight sections respectively. The Chapters are dedicated to finance, accounts and miscellaneous subjects (Ibid, § 32 – 43).

4.2 Analysing NHRC’s Compliance with the Paris Principles (Secondary Analysis)

The Principles give each country broad leeway in establishing an NHRI per their authority and capacity; however, the NHRI must adhere to the basic parameters set by the principles for its effective functioning (UNGA, 1993).

To develop a precise understanding of the parameters, the principles were further expanded and adopted by the GANHRI Bureau as the “General Observations of the Sub-Committee on Accreditation (SCA)” (GANHRI, 2019, art.11.2; GANHRI SCA, 2019, art.2.2). The General Observations (GO) are divided into two sections: the first contains the essential requirements outlined in the “Paris Principles”, and the second contains the practises that aid in achieving the “Paris Principles” essential requirements (CHRC, 2017, p.15). The GOs were last revised and adopted by the GANHRI at its Meeting held in Geneva (GANHRI, 2018). The GOs assist the SCA in providing better clarity for evaluating the NHRIs in the accreditation process (CHRC, 2017, p.15).

Using the Principles and the GOs, the authors attempt to assess the NHRC’s structural compliance as laid out in the PHRA; simultaneously, the authors also reflect on the practical aspect of the principles through the NHRC’s operations as reported in its most recent annual reports, i.e. 2018-2019 and 2019-2020. In doing so, the authors will concentrate on four key areas for evaluation: pluralism, independence, financial and administrative autonomy, and a broad mandate.

4.2.1 Pluralistic representation within the composition of the NHRC vis a vis Independence

The PHRA sets out the basic framework of the NHRC. The NHRC comprises six members, inclusive of the Chairman (PHRA, 1993, § 3(2)(a) -(c)). Out of the six members, three members of the commission belong to the following pool:

I.The Chairman of the NHRC - former Chief Justice/ Judge of the Supreme Court of India,

II.Judge of the Supreme Court [Serving or Former],

III.Chief Justice or a Judge of a High Court [Serving or Former]. (Ibid, § 3(2))

The remaining three members, out of which at least one has to be a woman, should be people “who have the knowledge or practical experience in matters relating to human rights” (Ibid, § 3(2)d)). Apart from them there are seven extra “deemed members” of the commission. These comprise chairpersons of the National “Sister Commissions”1 of the NHRC, namely: The National Commissions for [the Backward Classes, Minorities, the Protection of Child Rights, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Women, and Persons with Disabilities] (Ibid, § 3(3)).

A critical analysis of the composition reveals the following:

i.The authors observe that as a sizable portion of the membership pool comprises members of the higher judiciary, it ipso facto restricts the diversity within the commission as necessitated under the GOs (GANHRI, 2018, g.o 1.7). The GANHRI SCA Report held a similar view, wherein it pointed out that the quasi-judicial function of the commission is one out of many and therefore having the majority of its members from the judiciary fails to achieve the pluralism criteria under the Paris Principles (GANHRI, 2016).

ii.The presence of the respective chairman from the “Sister Commissions” within the commission is an excellent step towards achieving the pluralistic agenda under the Paris Principles. It guarantees that the grievances of the vulnerable are not brushed aside or go unnoticed (Sripati, 2000). However, the secondary analysis of the annual reports of the NHRC, the authors observe that there is hardly any interaction between the NHRC and its “Sister Commissions”. The “Sister Commission” are only mentioned once in the annual report, under the heading “Statutory Full Commission Meeting” (NHRC, 2019, p.83). The initiatives or decisions taken by the NHRC also do not refer to any collaboration with any of the “Sister Commissions” (Ibid, pp.1-287).

iii.The authors observe that the phrase “people with knowledge or practical experience in matters relating to human rights” contributes to the requirement of pluralism by including a wide range of stakeholders with practical and theoretical knowledge of human rights within the NHRC membership. (GANHRI, 2018, g.o 1.7). However, the authors caution that the criteria for selecting non-legal members should primarily be based on a person’s commitment to human rights and not on the prestigious position held by the candidate.

iv.An observation on the under-representation of women within the commission was made by the GANHRI SCA Report wherein it pointed out that women represented 20% of the total staff of the NHRC (GANHRI, 2016, p.24). The authors opine that mandatorily appointing one woman member out of the three non-judicial members of the commission is a welcome move in addressing the need for women’s representation within the commission (PHRA, 1993, § 3). The authors, however, opine that given the commission’s already minuscule representation of women as stated before, the above initiative falls short of its goal (GANHRI, 2016).

4.2.2 Selection and Appointment Procedure of the Members of NHRC vis a vis Structural Independence

An essential criterion for an institution’s smooth functioning and credibility is its independence, and one of the factors which directly reflects upon the autonomy of the NHRI is its method of appointment. The SCA suggests that the best method of appointment is that which depicts utmost transparency through broad participation and merit-based selection (GANHRI, 2018, g.o 1.8). A fixed tenure and an expressly laid down method of dismissal within the parent legislation further contribute to the institution’s independence. (Ibid, g.o 2.1).

According to the PHRA all commission members are appointed by the President of India, who acts on the advice of an “appointing committee” (PHRA, 1993, § 4). The “appointing committee” consists of six members –

i.The Prime Minister of India,

ii.The Speaker of the Lok Sabha2,

iii.The Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha3,

iv.The Union Minister in charge of the Ministry of Human Affairs,

v.The Leaders of the Opposition in the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha respectively (Ibid).

Moving forward to the criteria of tenure and dismissal, the PHRA provides for a fixed term of office for all its members. The duration of the tenure is three years from the day of the appointment or until a member attains the age of 70 years, whichever is earlier (Ibid, § 6). The PHRA further permits the reappointment of members for another term. The reappointed member should however not exceed the age of 70 years (Ibid).

When it comes to removing or dismissing members within the commission, the PHRA is exhaustive on terminating a member’s services (Ibid, § 5(3)). The PHRA gives the President of India the authority to remove a member found guilty on any of the five grounds specified in the Act (Ibid). In case of proven misbehaviour and incapacity, the members can only be removed by the president’s order following a Supreme Court inquiry (Ibid, § 5(2)).

A critical analysis of the appointment method and tenure/ method of dismissal reveals the following:

i.The PHRA does not prescribe any particular criteria and process for how members should be selected or what the benchmarks would be for scrutinising the eligible candidates. The PHRA only outlines the pool from which the members can be selected. Another concern is the need for more consultation with relevant stakeholders in the recruitment process. The authors thereby opine that there is an urgent need for the commission to adopt a more transparent recruitment process; doing so shall also assist in maintaining diversity within the NHRC. The process should include posting job openings, a thorough vetting process, and pre-set criteria for appointment (GANHRI, 2018, g.o 1.8). The authors further opine that the commission’s Chairman should be involved within the appointment committee while appointing the commission’s other members.

ii.The authors opine that the scorecard of the PHRA is optimistic in terms of establishing a fixed tenure and method of removal of members. According to the authors, the fixed-term period of service helps ensure the institution’s independence and the continuation of the commission’s programmes and initiatives. The dismissal method grants members security from arbitrary or discretionary dismissal.

4.2.3 Financial and Administrative Autonomy

Adequate funding, resources, and independent staff members are vital in maintaining the independence of an institution.

An estimated budget is prepared per the annual requirement of the NHRC by the accounts wing of the commission (NHRC, 2018, p. 173). The budget is approved by the Secretary General (SG) of the NHRC and is placed before the steering committee headed by the chairman of the NHRC (Ibid). After the committee approves the estimated budget, the budget is forwarded to the government (Ibid). The NHRC after that receives parliament-approved grant from the Government of India and has the liberty to spend it accordingly to achieve its mandate (PHRA, 1993, § 32).

Sufficient financial independence is also crucial in employing an efficient staff and procuring resources for the proper functioning of the institution. The NHRC is empowered to appoint its own administrative, technical and scientific staff (Ibid, § 11). The NHRC can additionally seek the assistance of the Central Government in appointing the SG and the police staff to conduct investigations into the complaints received by it (Ibid). In addition to this the NHRC is further empowered to appoint non -police members as observers or investigators to its investigative team (NHRC, 1994, reg. 48). Presently the NHRC employs a total of 295 staff members against the total sanctioned strength of 356 posts (NHRC, 2019, p. 228); these posts within the NHRC are divided into five divisions, i.e. Law, Investigation, Policy Research, Projects and Programmes Division, Training Division, and Administration Division (Ibid, p. 32).

i.The authors observe that the allocation of funding approved by the parliament ensures that there is no unnecessary denial of funds to the commission, thus ensuring the financial independence of the institution. The annual report of the NHRC suggests that the only financial hardship faced by the commission was in purchasing vehicles for the commission. (Ibid, p. 233).

ii.The authors further observe that the deployment of personnel for conducting investigations into complaints from the existing pool of police officers might be advantageous due to their prior held experience. However, given that many of the complaints received by the commission involve atrocities and excesses committed by their peers, selecting officers from the same force runs counter to the commission’s independence. The authors recommend that the commission exercise extreme caution in appointing the police and investigative staff and that only officers with impeccable records should be recruited. The authors further opine that non-police members should accompany the investigation team as observers or investigators (GANHRI, 2016, p. 26)

4.2.4 Broad Mandate

The PHRA confers the NHRC with a broad mandate on protecting and promoting human rights within the country (PHRA, 1993, § 12 ).

The authors divide the NHRC’s functions into four primary roles that it is authorised to play in carrying them out:

a.Protector (Ibid, §12(a -b)),

b.Promoter (Ibid, §12(g) – (i)),

c.Advisor (Ibid, §12(d) – (f)),

d.Monitor (Ibid, § (c) – (f)).

a. Commission as the Protector of Human Rights

As a protector of human rights, the commission has been ordained with the power to receive complaints and initiate an investigation into violations of human rights committed by a public servant (Ibid, § 12(a)). The commission’s power isn’t restricted to receiving complaints but can also suo motu initiate an investigation in an incident involving a rights violation, its abetment or negligence by a public servant in preventing such a violation (Ibid). To facilitate the NHRC in fulfilling this duty, the PHRA bestows it with the powers of a civil court in conducting an inquiry (Ibid, § 13(1)). The commission is empowered to summon witnesses, examine them under oath, receive evidence on affidavits, and order the production of any public record or copy thereof from any Court or office (Ibid). The commission is further vested with an investigative team to conduct its investigations into the complaints received by it. The commission can, after that, submit its results and recommendations to the concerned government for the appropriate action to be taken (Ibid, § 18). It is to be noted that the commission is only empowered to entertain complaints against public servants and not those involving private individuals (Ibid, § 12(a)).

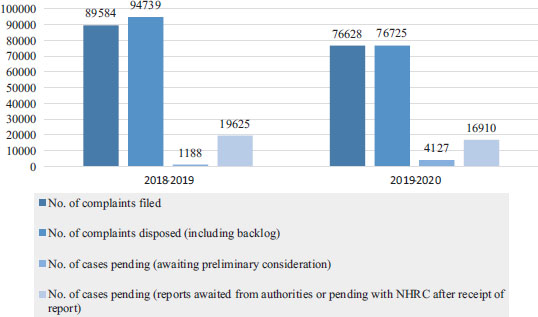

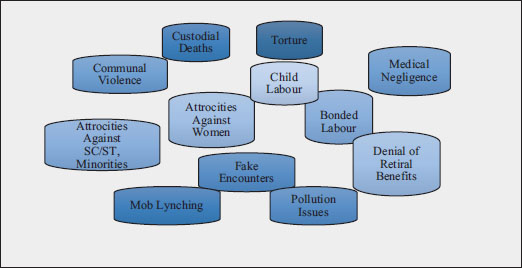

The annual reports of the NHRC depict that for the ease of filing complaints, the NHRC started a joint online facility wherein a complaint can be filed either with the NHRC or SHRCs (NHRC, 2019, p. 9). As a result, NHRC’s effectiveness and accessibility can be depicted from the no. of complaints received and the disposal rate. The NHRC received 1,66,212 complaints from 2018 -2019 (see fig. 5 below). The complaints received from the various states included a wide range of human rights issues (see fig. 6 below). The reports further depict the skillfulness of the NHRC in handling these complaints through its intensive investigations and speedy redressal of grievances, through the creation of “Rapid Action Teams” [RAT] (Ibid). The RAT have been created to deal with cases requiring urgent action (Ibid, p. 35).

Fig. 5. Statistics of complaints filed and pendency rate.

(Source: Secondary Analysis of the NHRC Annual Reports).

Fig. 6. Human Rights Issues for which complaints are filed before the NHRC.

(Source: Secondary Analysis of the NHRC Annual Reports).

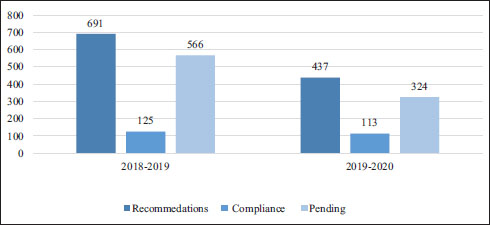

However, the rate of pendency (see fig. 7 below), could be more apparent. Any delay in securing remedies for the victims nullifies the motive of the NHRC. Further, the sheer number of complaints, although portrays that the citizens are aware of the commission and hold a sense of trust in the commission, the low rate of compliance (see fig. 7 below) shows non-cooperation from the government authorities as a significant hindrance in the performance of the NHRC. The NHRC, in its reports, mentions how it has repeatedly communicated and appealed to the defaulting governments/ authority to comply with its recommendations of providing monetary compensation (Ibid, p. 26).

Fig. 7. Statistics of compliance rate.

(Source: Secondary Analysis of the NHRC Annual Reports).

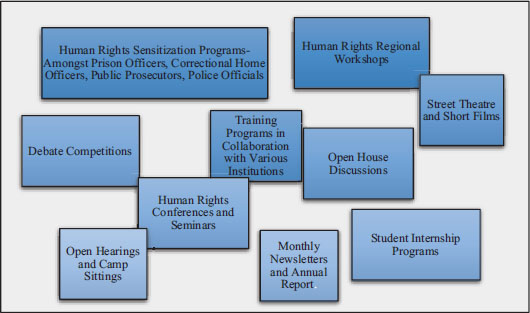

b. Commission as the Promoter of Human Rights

India is home to the largest illiterate population, and spreading awareness amongst the masses about their fundamental rights and duties is an urgent need of the hour (TOI, 2022). The commission has been tasked to undertake literary activities in spreading human rights awareness among various sections of society (PHRA, 1993, §12(h)). The authors observe that the NHRC has been active in undertaking numerous literary activities to spread human rights awareness (see fig. 8 below). The authors however opine that the awareness activities undertaken by the commission are less intensive within the rural and remote areas of the country. The authors further observe that the PHRA requires the NHRC to submit an annual report to the Central Government outlining the commission’s work (Ibid, § 20). The importance of publishing an annual report regularly is to provide a public account of the commission’s work and to allow for public scrutiny (GANHRI, 2018, g.o 1.11). It also helps to reflect on the institution’s effectiveness and legitimacy in terms of human rights protection. The NHRC still needs to meet obligations in this regard, as indicated by the fact that the NHRC fails to publish its annual report on time (Extra Judicial Execution Victim & Anr. v. Union of India & Ors., 2012). This is supported by the fact that the most recent publicly available annual report in 2023 is for the fiscal year 2019-20.

Fig. 8. Major Activities Undertaken by the NHRC for promoting Human Rights.

(Source: Secondary Analysis of the NHRC Annual Reports).

c. Commission as an Advisor for Human Rights

The commission’s function as an advisor is to assist the government in effectively implementing human rights norms endorsed within domestic and international instruments (PHRA, 1993, §12(f)). The NHRC constituted a special committee for studying the UN treaties and other international instruments on human rights to advise the government on the practical implementation of laws within the country (NHRC, 2019, pp. 166- 167). As part of the monitoring and advisory process, the commission further has the authority to review existing laws and offer suggestions to improve their effectiveness (PHRA, 1993, § 12(d)). The NHRC, exercising this function, reviewed some of the legislation/bills and put forth its recommendations for necessary amendments (See Fig No. 9 below). The NHRC additionally put forth advisory guidelines for the prevention of custodial violence (NHRC, 2018, p. 34 -35).

Fig. 9. Legislations on which the NHRC advised the government.

(Source: Secondary Analysis of the NHRC Annual Reports).

Commission as a Monitoring Agency for Human Rights

The commission’s role as a monitoring agency is to keep track of instances of human rights violations in the country. The PHRA (1993, §112(c)) empowers the commission with the right to visit prisons, jails, shelters, reformation houses or any such institution within the control of the government. The annual reports illustrate gamut of monitoring activities, such as jail visits by the special rapporteur in 52 cities between 2018-2020 (NHRC, 2018, pp. 75-76; NHRC, 2019, pp. 47-50) and special rapporteur visit to mental health institutions(NHRC, 2018, pp. 93-94). By doing so, the NHRC helped draw the government’s attention to specific areas where systemic reforms were required.

A critical analysis of the NHRC’s mandate depicts the following:

i.The authors opine that the PHRA fully complies with the Paris Principles regarding setting forth a broad mandate for promoting and protecting human rights within the legislation.

ii.The authors further observe that the PHRA, 1993 under Section 2(1) (d), adopts a broad definition of “Human Rights,” which tends to include all of the rights enshrined in international, regional, and domestic instruments (GANHRI, 2018, g.o 1.2). Thereby empowering the commission to receive and intervene into instances of all the rights violation (i.e. civil, political, social, economic, cultural etc.).

iii.The authors further observe that although the “Paris Principles” do not mandatorily require an NHRI to have a complaint redressal mechanism (GANHRI, 2018, g.o 2.9), the PHRA however goes a step further by granting the commission quasi-judicial authority.

5. STATUTORY LIMITATIONS IN THE WORKING OF THE NATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION

The NHRC is an independent body, not subservient to any agency. However, one must remember that the commission’s functioning, to some extent, can never be detached from the State. As a result, scepticism about the State’s commitment to establishing a solid and independent institution for investigating its State agents is entirely justified. (Sripati, 2000, p.16). To keep scepticism to a minimum, the drafters of the PHRA have done an excellent job by entrusting the commission with a broad mandate and powers to ensure its independence (PHRA, 1993, § 12). The commission’s past performance and active intervention in numerous incidents of human rights violations has further instilled trust in the commission’s working amongst the masses(Singh, 2018).

However, the authors opine that while the NHRC has established its credibility and worth against the stigmas of being yet another institution, some inherent weaknesses within the statute continue to act as barriers in the commission’s functioning time and again.

5.1 Legal Constraints

Section 18 (PHRA, 1993) states that wherein the commission’s findings disclose a human rights violation, it may “recommend” to the concerned government or authority to compensate or initiate prosecution against the delinquent officer. The PHRA, however, does not provide for a mechanism to make the recommendations mandatorily enforceable against the concerned government or authority.

India has approximately one billion people, more than 60% of which reside in the rural areas (Kapoor, 2022). As a result, the NHRC, which provides a straightforward method for filing complaints and a thorough outreach programme, serves as a safety net for the underprivileged and vulnerable. However, the nation as a whole gets negatively impacted if the NHRC’s recommendations are dismissed and not taken seriously. With such restricted recommendatory authority, the commission’s ability to uphold human rights is thereby rendered ineffective, and the citizen’s right to access justice is blatantly denied.

5.2 Jurisdictional Constraints

The international brunt of the atrocities inflicted upon the citizens by the military forces due to the applicability of special acts such as the “Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 [AFSPA]” gave birth to the commission (Banerjee, 2003). However, it is paradoxical that the commission lacks full-fledged powers to investigate allegations of human rights violations levied against armed forces (PHRA, 1993, § 19). The commission only has the power to seek a report from the Central Government either on its motion or based on a petition involving a human rights violation by the armed forces; the commission, on receipt of the said report, makes the necessary recommendations to the government; the government, as a result, has to submit its comments only on the action taken by it upon the requests within three months (Ibid).

Presently, the AFSPA is applicable within the districts of five states of India i.e. “Kashmir, Assam, Manipur, Nagaland, and Arunachal Pradesh”(Hub Network, 2023). Controversies surrounding the Act within the aforementioned areas have been repeatedly brought forth by various human rights outfits (Ibid). The controversies include alleged “fake encounters” and torture against civilians by armed personnel (Extra Judicial Execution Victim & Anr. v. Union Of India & Ors., 2012). Giving restricted jurisdiction to the NHRC w.r.t the armed forces, is thereby detrimentally in two ways:- First that it can lead to some of the gravest human rights violations to go unattended, thereby violating the victims’ and survivors’ rights to justice and redressal (Amnesty International, 2015; Human Rights Report, 2022) and second, that it creates doubt and hostility in the minds of the public against the armed forces due to the lack of transparency in military trials (CHRI, 1998, pp. 5-6).

5.3 Limitation in taking Cognizance of the Complaints

The Commission is prohibited from investigating complaints where the alleged human rights violation occurred more than one year before the date of filing the complaint (PHRA, 1993, § 36(2)).

Atrocities committed against women and the weaker sections of the society are some of the gravest human rights violations within the country. The data of the NCRB depicts that a total of 4,28,278 cases of crime against women and 59,702 cases of crime against persons belonging to the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes were committed in 2021 (NCRB, 2021). Given the prevalent inequality in society, there are numerous barriers - social and economic - that can prevent a victim of a human rights violation from approaching authorities on time. Many citizens in the country’s rural and remote areas may be unaware of the institution. Because of a lack of support at home, victims may lack the courage to approach the institution. As a result, by the time they are made aware of it or muster the courage to file an official complaint, the complaint may become non-cognizable due to time constraints. As a result, the authors conclude that the one-year limitation period becomes a significant impediment to obtaining justice in many genuine cases.

6. WAYS TO ENHANCE THE CAPABILITIES OF THE NHRC

6.1 The Indian Judiciary on the Protection Of Human Rights Act, 1993

i. DK Basu v. State of West Bengal, 1986

While considering the application filed by Amicus Curie on the failure of the State Governments (SG) to establish SHRCs and HRCs, the Hon’ble Supreme Court (SC) dwelt on the response filed by the states (DK Basu v. State of West Bengal, 1986). The Hon’ble Supreme Court rejected the SG’s long-standing claim that the use of the word ’may’ in section 21 was directory in nature and did not make it mandatory for the states to establish a SHRC (Ibid).

The court accordingly held that

“Whether or not the word ’may’ should be construed as mandatory and equivalent to the word ’shall’ would depend upon the object and the purpose of the enactment under which the said power is conferred as also related provisions made in the enactment” (Ibid).

As a result, the court directed all the defaulting states to mandatorily set up SHRC(s) within their respective states, without further delay (Ibid). The Court further observed that the failure to establish a SHRC is violative of the citizens “right to access justice” under Article 21 of the Constitution of India (Ibid).

The Court stated

“Human rights violations in the States that are far removed from the NHRC headquarters in Delhi itself makes access to justice for victims from those states an illusion… We need to remember that access to justice so much depends upon the ability of the victim to pursue his or her grievance before the forum competent to grant relief”(Ibid).

ii. Extra Judicial Execution Victim & Anr. v. Union Of India & Ors., 2012

While hearing the current petition, the NHRC drew the attention of the Supreme Court to some of the difficulties it encountered in carrying out its responsibilities (Extra Judicial Execution Victim & Anr. v. Union Of India & Ors., 2012). It claimed that the institution receives a huge number of complaints on a daily basis and hence has been requesting the Central Government for an adequate number of trained people. The government however has turned a deaf ear to its repeated pleas.(Ibid).

The Court in response to this observed that

“Considering that such a high powered body has brought out its difficulties through affidavits and written submissions filed in this Court, we have no doubt that it has been most unfortunately reduced to a toothless tiger. We are of the clear opinion that any request made by the NHRC in this regard must be expeditiously and favourably respected and considered by the Union of India otherwise it would become impossible for the NHRC to function effectively and would also invite avoidable criticism regarding respect for human rights in our country” (Ibid).

The court thereby urged to the Union Government to take note of the commission’s concerns and address them as soon as possible in order to achieve the goals of justice (Ibid).

iii. State of Uttar Pradesh v. National Human Rights Commission, 2016

The Hon’ble Allahabad High Court dwelt upon the question – “whether the use of the expression ’recommend’ in Sections 12 and 18 (PHRA, 1993) can be treated as merely an opinion or a suggestion likely to be ignored at will by the respective Government or authority” (State of UP v. NHRC, 2016)

In response to the question, the division bench ruled that the authorities are absolutely bound by the recommendations made by the NHRC/SHRC, as anything contrary to that would render the institution infructuous (Ibid). The Hon’ble Court further stated that because the PHRA does not grant the right to file an appeal, the only option available to the concerned government or authority in the event of disagreement with the recommendation is to seek judicial review (Ibid).

iv. Abdul Sathar v. Principal Secretary to Government, Home Department, 2021

Following the same line of reasoning prescribed by the Hon’ble, Allahabad High Court, a full bench of the Hon’ble Madras High Court held that –

“the recommendation is binding, the State has no discretion to avoid implementation of the recommendation and in case the State is aggrieved, it can only resort to legal remedy seeking judicial review of the recommendation of the Commission” (Abdul Sathar v. Principal Secretary to Government, Home Department, 2021).

The court further recommended that Section 18 of the Act be amended to include an internal mechanism for enforcing its recommendations (Ibid).

v. Paramvir Singh Saini V. Baljit Singh & Ors., 2020

The Hon’ble SC court directed all the State Governments to designate HRCs in each district of the state (Paramvir Singh Saini V. Baljit Singh & Ors., 2020). The court additionally directed every police station within the state to

“prominently display at the entrance and inside the police stations/offices of investigative/enforcement agencies about a person’s right to complain about human rights violations to the NHRC/SHRC, HRC or the Superintendent of Police or any other authority empowered to take cognizance of an offence”(Ibid).

In light of the Statutory limitations within the PHRA, 1993 and the views given by the Indian Judiciary on some of the provisions of the PHRA, 1993 the authors propose the following amendments to the PHRA, 1993 for improving the NHRC’s compliancy with the “Paris Principles”.

6.2 Proposed Amendments to the PHRA, 1993

a) Maintaining Plurality within the Commission

Maintaining plurality within the commission is the first and foremost requirement in strengthening the institution. The presence of members from diverse backgrounds, such as NGOs, civil societies, humanitarian groups, lawyers, doctors, etc., has a three-pronged effect, first, it helps in maintaining the institution’s independence; second, it helps in effectively achieving its mandate due to their more extensive outreach and third it helps in gaining public confidence. The PHRA presently only outlines the pool from which the members can be selected. The authors thereby suggest an amendment to the Act to expressly lay down the criteria as well as the procedure for the appointment of the members. This would thereby help include passionate and experienced members of society to serve as the country’s guardians of human rights. The authors additionally, suggest that the commission should actively maintain communication with its “Sister Commissions” to benefit from their experiences in handling complaints specific to the groups that the respective commission caters to. Furthermore, complaints that fall out of the jurisdiction of the NHRC, such as human rights violation committed by a private person, can be referred to the appropriate “sister commission” (NHRC, 1994, reg.9).

b) Greater Financial Independence

Adequate financial autonomy is one of the primary considerations for any independent institution to carry out its business. The NHRC has often been seen in the past, talking about its constant struggle with the scarcity of resources (Verma, 2020). With the NHRC going digital and increasing awareness about the institution’s existence, it is bound to get bombed with a bulk caseload, requiring added workforce to manage the work. The fact that presently the cent al government reserves the right to make the final decision on the NHRC’s budget raises the possibility of political meddling (PHRA, 1993, § 32). The authors thereby suggest an amendment to Section 32, PHRA4. Wherein the Central Government should be required to pay the Commission amount that the Parliament has approved after making the proper allocations without any restriction.

c) A Permanent and Independent Special Investigative Teams (SIT)

The PHRA, 1993 states that if the commission believes it is appropriate to proceed with an investigation, it may seek the assistance of any officer or investigation agency under the authority of the State/Central Government (Ibid, § 11). Given the majority of complaints the commission receives, police officials are often drawn from the existing pool of police forces (GANHRI, 2017, p.20). The involvement of police officers investigating complaints, particularly in complaints wherein their fellow police officers are accused of human rights violations, go against the tenets of natural justice. In this regard, the authors suggest that an amendment should be made to Section 37 of the PHRA.

Section 37, presently states that

“Notwithstanding anything contained in any other law for the time being in force, where the Government considers it necessary so to do, it may constitute one or more special investigation teams (SIT), consisting of such police officers as it thinks necessary for purposes of investigation and prosecution of offences arising out of violations of human rights”.

The authors suggest that the SITs constituted under Section 37 (PHRA, 1993) should be made permanent and exclusively attached to the NHRC. The recruitment process and transfers made to such SITs should be strictly done in consultation with the NHRC members (Sripati 2000, p.32). This is to avoid any foul play. Additionally, the eligible pool for the SIT should preferably be restricted to the new batch of police officials (Ibid). The reason for doing this is to avoid any sort of bias and the ease of giving specialised sensitisation training in handling human rights complaints to the fresh recruits. In addition to the police officials, SIT should also be inclusive of experts of different competencies (Thanawala, 2022). This would help maintain transparency in the investigative process.

d) Power to Make Enforceable Orders and Refer Litigation

The authors contend that the commission currently lacks the teeth to uphold its statements, directives, or recommendations. The authors thereby propose that the Act be modified to grant the commission the authority to issue directives and make pertinent decisions. It should also have the authority to take legal action against a person or authority that disobeys its directives or prevents it from carrying out its mandate. The Act has to be amended to explicitly include that the recommendations and the directions are binding in nature and a deadline should be set for the implementation of such orders. The Act should also specify what to do in the event when the recommendations are not implemented.

e) Establishing and Enhancing Cooperation with State Human Rights Commissions (SHRC)

Due to the vastness of the country, the Human Rights Act empowers all the State Governments to establish a SHRC within their borders (PHRA, 1993, § 21).

At present, there are 25 states out of the 28 states which have established a SHRC within their jurisdiction (NHRC, no date). Out of theses 25 states, SHRCs from only four (4) states namely, Bihar, Karnataka, Kerala and Maharashtra, are functioning under the “Human Rights Commissions Network” an online portal created for commissions (HRCN, no date). The online portal helps in providing a centralised approach to handling human rights complaints.

Given the enormity of the caseload the NHRC faces, the establishment and proper functioning of the SHRCs would allow for faster access to a decentralised complaints redressal mechanism (Ray, 2003, p. 509). Additionally, it would also help the aggrieved parties save money on travel expenses (Ibid) Furthermore doing so shall also help the NHRC to divert its efforts and time towards the plethora of responsibilities it has been entrusted with as an NHRI. The authors thereby urge the State Governments to muster their efforts towards establishing SHRCs where they are non-existent and initiate action to bring the defunct SHRCs back into operation (NHRC, 2019, p.81).

f) Establishing and Enhancing Cooperation with District Human Rights Courts

Section 30 of the PHRA directs the State Governments to designate every district criminal court within the state to be designated as a HRC. At present 23 out of 28 states and 6 out of the 7 UTs are in compliance with the section (Ibid, p.85).

The NHRC and the SHRCs although devoid of the power to prosecute public servants for offences arising from human rights violations; have the power to recommend prosecution for the deviant public official (PHRA, 1993, § 18(a) (ii)). Between 2021 and 2022 itself the NHRC received 2307 cases of custodial deaths from across the country (Jain, 2022). However, no prosecution was directed in any of the cases (Ibid). The authors believe that simply awarding compensation for such gruesome violations appears to fall short of the government’s obligation to provide an effective remedy (Pinto, 2018, p. 174). The authors thereby suggest that the NHRC/SHRC and the HRCs should work in unison, as doing so shall bring in more credibility to the work done by the NHRC/SHRC. Whenever the commission’s investigation reveals that a criminal act, i.e. “an offence arising out of violation of human rights” has been committed, the commission should either directly refer its findings to the prosecuting authority, i.e. the Special Public Prosecutor for Human Rights appointed to conduct cases in the HRC or direct the victim to approach the HRC. The commission should further use its power to intervene into proceeding involving a violation of human rights (PHRA, 1993, § 12(b)) to ensure that a thorough resolution of the issue raised in the complaint.

The authors opine that while the defaulting states must endeavour to establish the HRCs, the inherent defect within the Act pertaining to the functioning of the courts is a cause of concern. The provisions pertaining to HRCs within the PHRA are quite restricted. The PHRA merely provides for the establishment of these courts, with no additional explanation on the court’s mandate and powers (NHRC, 1996, p.56). Thereby, creating confusion. As a result, the authors propose that Section 30 (PHRA, 1993) be revised to expand the powers and scope of the courts. The proper functioning of the HRCs can be a breather for the victims of gruesome human rights violations, and will additionally help the NHRC achieve its mandate of protecting human rights in the country.

7. CONCLUSION

Theoretically, the NHRC complies with the “Paris Principles”. The commission has been given a broad mandate, particularly in taking suo moto cognizance of complaints. Through this the NHRC’s work has been both preventive and penetrative. The commission’s activities are diverse, focusing on political and civil rights and actively promoting economic, social, and cultural rights. However, certain flaws, such as the lack of pluralism within the commission members, lack of a permanent and independent investigative teams, non- cooperation from the governments’ in honouring the recommendations of the commission, financial crunch, lack of manpower, jurisdictional constraints, and so on, impede the commission’s ability to function effectively.

This is not to say that the commission should be crippled by its limitations. On the contrary, it should focus on developing new methods and practices for promoting and protecting human rights such as utilizing the potential of the existent district HRCs and the SHRCs, while equivalently advocating for the necessary amendments to the PHRA (1993).

REFERENCES

Primary Sources

International Treaty Law

UDHR (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights, GA Res. 217 A (III) UN Doc. A/810.

International Law

GANHRI (2019). Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions Statue, GANHRI and OCHCR, 5 March, 2019.Available at https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/NHRI/GANHRI/EN_GANHRI_Statute_adopted_05.03.2019_vf.pdf

GANHRI SCA (2019). Rules of Procedure for the GANHRI Sub-Committee On Accreditation, GANHRI, 4 March, 2019. Available at: https://www.ohchr.rg/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/NHRI/GANHRI/ENG_GANHRI_SA_RulesOfProcedure_adopted_04.03.2019_vf.pdf

National Constitutions

The Constitution of India, 1950

National Law

PHRA (1993). The Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 Act No. 10 of 1994.

NHRC (1994). The National Human Rights Commission (Procedure) Regulations. National Human Rights Commission, New Delhi, Available at: https://thc.nic.in/entral%20Governmental%20Regulations/National%20Human%20Rights%20Commission%20(Procedure)%20Regulations,%201994.pdf.

National Case Laws

Abdul Sathar V. Principal Secretary to Government, Home Department (2021). LNINDORD 2021 MAD 13.

DK Basu v. State of West Bengal (1986). Writ Petition (CRL.) No. 539 of 1986.

Extra Judicial Execution Victim & Anr. v. Union Of India & Ors. (2012). Writ Petition (Crl.) No. 129 of 2012.

Paramvir Singh Saini V. Baljit Singh & Ors. (2020). Special Leave Petition (Criminal) No. 3543 of 2020.

State of Uttar Pradesh v. National Human Rights Commission (2016). Writ Petition (C) No. 15570 of 2016.

Secondary Sources

International Resolutions

UNGA (1977). Observance of the 30th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations General Assembly, 129, Doc A/RES/32/123.

UNGA (1979). National Institutions for Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, United Nations General Assembly, Resolution No. 34/49.

UNGA (1981). National Institutions for Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, United Nations General Assembly, Resolution No. 36/ 134.

UNGA (1993). National Institutions for Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, United Nations General Assembly, Resolution No. 48/ 134.

International Reports

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL (1989). Amnesty International Annual Report, Amnesty International, POL 10/0002/1989. London, UK, pp 174–178. Available at: https://www.amnest.org/en/documents/po110/0002/1989/en.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL (2015). Denied Failures in Accountability in Jammu and Kashmir, Amnesty International, July 1, 2015 pp. 1–80. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa20/1874/2015/en.

CHRC (2017). A Practical Guide to The Work of the Sub-Committee on Accreditation (SCA). Canadian Human Rights Commission and GANHRI, December 2017. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/NHRI/GANHRI/GANHRI_Manual_online.pdf.

GANHRI (2016). Report and Recommendations of the Session of the Sub-Committee on Accreditation, GANHRI, Geneva, pp. 24–28.

GANHRI (2017). Report and Recommendations of the Session of the Sub-Committee on Accreditation, GANHRI, Geneva, Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/NHRI/GANHRI/SCA_Report_November_2017_-_ENG.pdf.

GANHRI (2018). Report and Recommendations of the Session of the Sub-Committee on Accreditation, GANHRI, Geneva, Available at: https://www.ohchr.rg/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/NHRI/GANHRI/EN_GeneralObservations_Revisions_adopted_21.02.2018_vf.pdf.

HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT (2022). Human Rights Report, India 2022 – Executive Summary, U.S Department of State. Available at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/415610_INDIA-2022-HUMAN-RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf.

OHCHR (1993). Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna, The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Vienna. Available at: https://www.ohchr.rg/sites/default/files/vienna.pdf.

OHCHR (2023). Chart Of The Status Of National Institutions (Accreditation Status), Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Available at: https://www.ohchr.rg/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/NHRI/StatusAccreditationChartNHRIs.pdf.

TOI, (2022). 75 years, 75% literacy: India’s long fight against illiteracy, Times of India, 14 August, 2022, Available at: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/75-years-75-literacy-indias-long-fight-against-illiteracy/articleshow/93555770.cms.

UNCHR (1992). National Institutions for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights. United Nations Commission on Human Rights. Available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f22a70.html.

UNDHR (1978). Seminar on National and Local Institutions for Promoting and Protecting Human Rights, ST/HR/SER/A.2, United Nations Division Of Human Rights, Geneva: United Nations. Available at: https://digitallibary.un.org/record/731550/files/.

UNDP-OHCHR (2010). UNDP-OHCHR Toolkit For Collaboration with National Human Rights Institutions, United Nations Development Programme And Office Of The High Commissioner For Human Rights. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/NHRI/1950-UNDP-UHCHR-Toolkit-LR.pdf.

UNECOSOC OFFICIAL RECORDS (1960). Report to the Economic and Social Council on the sixteenth session of the Commission on Human Rights, United Nations Commission on Human Rights and United Nations Economic And Social Council, pp. 1–147. Available at: https://digitallibary.un.org/record/220212?ln=en.

National Reports

CHRI (1998). Submission to Advisory committee of the National Human Rights Commission to review the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993, Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, New Delhi, pp. 1–26. Available at: https://humanrightinitiative.org/publications/hrc/submission_adv_comm_nhrc_hr_protect_act.pdf.

NCRB (2021). Crime in India 2021 Statistics – Volume I, National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs. Available at: https://ncrb.gov.in/sites/default/files/CII2021/CII_2021Volume%201.pdf.

NHRC (1996). Annual Report 1996 -1997 National Human Rights Commission, New Delhi. Available at: https://nhrc.nic.in/annualreports/1996-97.

NHRC (2012). A Handbook on International Human Rights Conventions, National Human Rights Commission, New Delhi, 10 December 2012. Available at: https://nhrc.nic.in/sites/default/files/A_Handbook_on_on_International_HR_Conventions.pdf.

NHRC (2018). Annual Report 2018 -2019, National Human Rights Commission, New Delhi. Available at: https://nhrc.nic.i/sites/default/files/Annual%20Report%202018-29_final.pdf.

NHRC (2019). Annual Report 2019 -2020 National Human Rights Commission, New Delhi. Available at: https://nhrc.nic.i/sites/default//files/AR_2019-2020_EN.pdf.

Books and Articles

BANERJEE, S. (2003) “Human Rights in India in the Global Context”, Economic and Political Weekly, 38(5), pp. 424–425. Available at: https://www.jstor.rg/stable/4413153.

CHAUHAN, N. (2018) “NHRC retains its “A” status of accreditation with GANHRI in Geneva”, Times of India, 23 February. Available at: https://timesofinda.indiatimes.com/india/nhrc-retains-its-a-status-of-accreditation-with-ganhri-in-geneva/articleshow/63047908.cms.

DEOL, S.S. (2011). “Human Rights in India: A Theoretical Perspective”, Human Rights in India: Theory and Practice.

GHOSAL, S.G. (2010). “Human Rights: Concept and Contestation”, Indian Political Science Association, 71(4), pp. 1103–1125. Available at: https://www.jstor.rg/stable/42748940.

GHOSH, J (2017). “Indira Gandhi’s Call Of Emergency And Press Censorship In India: The Ethical Parameters Revisited”, Global Media Journal, 7(2), June, 2017. Available at: https://www.caluniv.ac.in/global-mdia-journal/Article-Nov-2017/A4.pdf.

HEGDE, V.G. (2018). “International Law in the Courts of India”, Asian Yearbook of International Law, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004379756_003.

HUB NETWORK (2023). “Is AFSPA the Need of the Hour or a Social Evil”, Hub Network, January 8 2023. Available at: https://hubnetwork.in/is-afspa-the-need-of-the-hour-or-a-social-evil/.

JAIN, B. (2022). “MHA to Lok Sabha: 2152 cases of deaths in judicial custody, 155 in police custody”, Times of India, 22 March, 2022. Available at: https://timesofinda.indiatimes.com/india/mha-to-lok-sabha-2152-cases-of-deaths-in-judicial-custody-155-in-police-custody/articleshow/90380779.cms.

JASWAL, P.S. AND JASWAL, N. (1996). “Human Rights and the Law”, APH Publishing Corporation, New Delhi.

KANNABIRAN (1992). “Why a Human Rights Commission?”, Economic and Political Weekly, 27(39), pp. 2092–2094. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4398933.

KAPOOR, M. (2022). “Rural Realities and Union Budget 2022-23”, Impact and Policy Research Institute, 7 February, 2022. Available at: https://www.impriindia.com/event-report/ruralrealities-budget-2022/.

KOTHARI, M. (2018). “India’s Contribution to the Universal Declaration on Human Rights”, Journal of National Human Rights Commission, India, 17, pp. 65–98, Available at: https://nhrc.nic.in/sites/default/files/JOURNAL_V-17_2018.pdf.

KUMAR, C.R. (2003). “National Human Rights Institutions: Good Governance Perspectives on Institutionalization of Human Rights”, American University International Law Review, 19(2), pp. 259–300. Available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/235401743.pdf.

MADAN, N (2017), History and Development of Human Rights in India, IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science, 22(6), June 2017, pp. 1–27. Available at: https://doi.org/10.9790/0837-2206090106

MILLER, R.H. (1968). “National Commissions on Human Rights”, Malaya Law Review, National University of Singapore (Faculty of Law), 10(2), pp. 157–177. Available at: https://www.jstor.rg/stable/24862562.

NARIMAN, F. S. (2013). “Fifty Years of Human Rights Protection in India - The Record Of 50 Years Of Constitutional Practice”, National Law School of India Review, 13–26. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44283607.

PINTO, M. (2018). “Awakening the Leviathan through Human Rights Law – How Human Rights Bodies Trigger the Application of Criminal Law”, Utrecht Journal of International and European Law, 34(2), pp. 161–184. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5334/ujiel.462

RANJAN, A. (2019). “The Generation Theory of Human Rights and its Dichotomy: The Justiciability of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights with Special Reference to the Constitutional Guarantees in India”, Journal of the Indian Law Institute, 61(2), 242–259. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27097363.

RAO, P.P. (1998). “Permeation of Human Rights Philosophy into Municipal Law”, Indian Law Institute, 40(1/4), pp. 131–137. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43953313.

RAY, A. (2003). “National Human Rights Commission of India: Formation, Functioning and Future Prospects”, Khama Publishers, New Delhi. Available at: https://books.google.co.in/books?id=e2di76mxj0IC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

SAHANI, V. (2017). “UN Report Recommends Deferring NHRC Accreditation Till Year End”, Live Law, 11 February, 2017. Available at: http://www-livelawin.gnlu.remotlog.com/un-report-recommends-deferring-nhrc-accreditation-till-year-end/.

SINGH, U.K. (2018). “The Inside -Outside Body”, Economic and Political Weekly, 53(5), 3 February, 2018. Available at: https://www.epw.in/journal/2018/5/perspectives/%E2%80%98inside%E2%80%93outside%E2%80%99body-.html?0=ip_login_no_cache%3Df48d7862f067d1fa0ad765432801c539.

SOMANATHAN, S. (2010). “Protection of Human Rights, Act -1993 – Human Rights Courts in India”, Indian Journal of Human Rights and Social Justice, 5(1-2) pp. 217–240.

SRIPATI, V. (2000). “India’s National Human Rights Commission: A Shackled Commission?”, Boston University International Law Journal, 18(1), pp. 1–46. Available at: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/138856/pdf.

SUGUNAKARARAJU, S. R. T. P. (2012). “Social Movements and Human Rights In India: An Overview”. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 73(2), 237–250. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41856586.