Miscelánea

water and landscape

AGUA y TERRITORIO

Variations in land use and land cover in a region of the brazilian Cerrado: A case study of the Farinha river basin, MA, and Chapada das Mesas National Park

Variaciones en el uso y cobertura del suelo en una región del Cerrado brasileño: un estudio de caso de la cuenca del río Farinha, MA y el Parque Nacional Chapada das Mesas

Cristiane Matos da Silva

Universidade Estadual da Região Tocantina do Maranhão – UEMASUL

Imperatriz, Brasil

cristiane.silva@uemasul.edu.br

ORCID: 0000-0002-6416-4413

ORCID: 0000-0002-6416-4413

Jurandir Pereira Filho

Universidade do Vale do Itajaí – UNIVALI

Itajaí, Brasil

jurandir@univali.br

ORCID: 0000-0002-7166-458X

ORCID: 0000-0002-7166-458X

Información del artículo

Recibido: 19/09/2023

Revisado: 22/03/2024

Aceptado: 10/04/2024

Online: 02/06/2024

Publicado: 10/01/2025

ISSN 2340-8472

ISSNe 2340-7743

cc-by

cc-by

© Universidad de Jaen (Espana).

Seminario Permanente Agua, Territorio y Medio Ambiente (CSIC)

ABSTRACT

This study examines the impact of human activity on soil and land use in the Farinha river basin, MA, and the Chapada das Mesas National Park over the past two decades. Satellite images from 2012 to 2020 were analysed to determine changes in land use and cover. The results reveal an increase in human activities, particularly grazing, in both areas during this period. This expansion of human activity poses threats to the environment, such as erosion processes, loss of water, soil, and nutrients. It emphasizes the importance of quantifying these losses and understanding their consequences. The findings highlight the need to protect sensitive areas like indigenous lands and conservation units to ensure the preservation and sustainability of natural vegetation and plant growth.

KEYWORDS: Flour River, Anthropisation, Pasture, National Park.

RESUMEN

Este estudio examina el impacto de la actividad humana en el suelo y el uso de la tierra en la cuenca del río Farinha, MA, y el Parque Nacional Chapada das Mesas en las últimas dos décadas. Se analizaron imágenes de satélite de 2012 a 2020 para determinar los cambios en el uso y la cobertura del suelo. Los resultados revelan un aumento de las actividades humanas, en particular el pastoreo, en ambas áreas durante este período. Esta expansión de la actividad humana plantea amenazas para el medio ambiente, como procesos de erosión, pérdida de água, suelo y nutrientes. Se subraya la importancia de cuantificar estas pérdidas y comprender sus consecuencias. Las conclusiones subrayan la necesidad de proteger zonas sensibles como las tierras indígenas y las unidades de conservación para garantizar la preservación y sostenibilidad de la vegetación natural y el crecimiento de las plantas.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Río Harina, Antropización, Pastos, Parque Nacional.

Variações no uso e cobertura da terra em uma região do Cerrado brasileiro: um estudo de caso da bacia do rio Farinha, MA e do Parque Nacional da Chapada das Mesas

RESUMO

Este estudo examina o impacto da atividade humana no solo e no uso da terra na bacia do rio Farinha, MA, e no Parque Nacional da Chapada das Mesas nas últimas duas décadas. Imagens de satélite de 2012 a 2020 foram analisadas para determinar as mudanças no uso e cobertura do solo. Os resultados revelam um aumento das atividades humanas, particularmente o pastoreio, em ambas as áreas durante este período. Esta expansão da atividade humana representa ameaças para o ambiente, tais como processos de erosão, perda de água, solo e nutrientes. O trabalho sublinha a importância de quantificar estas perdas e de compreender as suas consequências. Os resultados destacam a necessidade de proteger áreas sensíveis, como terras indígenas e unidades de conservação, para garantir a preservação e a sustentabilidade da vegetação natural e do crescimento das plantas.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Rio Farinha, Antropização, Pastagem, Parna.

Variations de l’utilisation et de la couverture des sols dans une région du Cerrado brésilien: étude de cas du bassin de la rivière Farinha, MA et du parc national Chapada das Mesas

RESUME

Cette étude examine l’impact de l’activité humaine sur l’utilisation des sols et des terres dans le bassin de la rivière Farinha, MA, et le parc national Chapada das Mesas au cours des deux dernières décennies. Des images satellites de 2012 à 2020 ont été analysées pour déterminer les changements dans l’utilisation et la couverture des sols. Les résultats révèlent une augmentation des activités humaines, en particulier du pâturage, dans les deux zones au cours de cette période. Cette expansion de l’activité humaine présente des menaces pour l’environnement, telles que les processus d’érosion, la perte d’eau, de sol et de nutriments. Elle souligne l’importance de quantifier ces pertes et d’en comprendre les conséquences. Les résultats soulignent la nécessité de protéger les zones sensibles telles que les terres indigènes et les unités de conservation afin d’assurer la préservation et la durabilité de la végétation naturelle et de la croissance des plantes.

MOTS CLÉ: Rivière à Farine, Anthropisation, Pâturage, Parc National.

Variazioni nell’uso e nella copertura del suolo in una regione del Cerrado brasiliano: un caso di studio del bacino del fiume Farinha, MA e del Parco Nazionale Chapada das Mesas

SOMMARIO

Questo studio esamina l’impatto dell’attività umana sul suolo e sull’uso del territorio nel bacino del fiume Farinha, MA, e nel Parco Nazionale Chapada das Mesas negli ultimi due decenni. Sono state analizzate le immagini satellitari dal 2012 al 2020 per determinare i cambiamenti nell’uso e nella copertura del suolo. I risultati rivelano un aumento delle attività umane, in particolare del pascolo, in entrambe le aree durante questo periodo. Questa espansione dell’attività umana comporta minacce per l’ambiente, come i processi di erosione, la perdita di acqua, suolo e nutrienti. Il rapporto sottolinea l’importanza di quantificare queste perdite e di comprenderne le conseguenze. I risultati evidenziano la necessità di proteggere le aree sensibili come le terre indigene e le unità di conservazione per garantire la conservazione e la sostenibilità della vegetazione naturale e della crescita delle piante.

PAROLE CHIAVE: Fiume di Farina, Antropizzazione, Pascolo, Parco Nazionale.

Introduction

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations1,land use is the basis for plant growth and contributes to the maintenance of natural and planted vegetation, including forests and grasslands in relation to the prevailing climate, landscape, and soil type. Its proper management is an essential factor in sustainable agriculture, providing a valuable source of climate regulation2.

Recent studies indicate that the higher the rate of deforestation, the higher the rates of gradual increase in temperature, causing a decrease in rainfall and, consequently, an increase in the concentration of CO2 resulting from fires3. These changes could lead to the extinction of species of local fauna and flora, jeopardizing the entire ecosystem and contributing to climate change on a global scale.

In Brazil, the state of Maranhão makes up the territory of the Legal Amazon, in which the Cerrado biome stands out, with diverse soils characterized by low nutrient availability due to long weathering times and high leaching rates 4. This region has been experiencing a growing increase in deforestation due to the advance of anthropogenic activities. Alarming data shows that in June 2021, 63 % of deforestation in the Legal Amazon occurred in private areas or under various stages of ownership. The rest was recorded in settlements (22 %), Conservation Units (13 %) and Indigenous Lands (2 %)5. The advance of agribusiness is jeopardizing very sensitive areas, since it can lead to the suppression of Indigenous areas and Conservation Units and, consequently, can cause erosion processes and changes in the use of soil and water. Against this backdrop, special attention must be paid to the advance of agribusiness into Cerrado areas. Data obtained by shows that from August 2019 to July 2020, deforestation in the Cerrado totaled 7,300 km2, equivalent to 13.2 % more than in the previous period6. This data, together with the mapping done by Prodes7, highlight the fragility of the Cerrado in the face of the advance of agribusiness, compromising sensitive areas of environmental preservation.

The Cerrado biome occupies 66.5 million hectares in the Matopiba region (Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia) where there has been strong agricultural expansion since the 1980s8. This expansion, with a few exceptions, has not led to significant deforestation, but to changes in land use and land tenure. For example, extensive such as extensive pastures in fields and savannahs that were replaced by mechanised agriculture, or areas next to the development of modern agricultural hubs contrasting with thousands of hectares occupied by low-productivity and low-profit agriculture. productivity and low profitability9.

In this context, it can be seen that agroforestry activities in the Matopiba region reveal a complex dynamic between agricultural production, environmental conservation and the sustainable management of natural resources. With particular emphasis on the compromises that agricultural expansion can bring to habitats and the ecological integrity of environmental preservation areas such as the Farinha river basin and the Chapada das Mesas National Park - MA, compromising endemic flora and fauna specimens becomes a crucial concern in the face of the advance of these activities.

River basins are important planning units, as the occupation model of these sites will directly influence regional water availability10. According to Pires et al. e Santos et al.11, among the methodologies aimed at studying and managing river basins are those that employ the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and the analysis of orbital images obtained by remote sensing. Remote sensing is the main tool for monitoring vegetation cover, as it allows data to be obtained from large areas at regular time intervals, without the need for extensive fieldwork12.

The Chapada das Mesas National Park is located between the municipalities of Carolina, Estreito and Riachão in the south-west of the state of Maranhão, covering a total area of 160,000 ha (one hundred and sixty thousand hectares) of cerrado, divided into two glebes, where the first has an area of approximately 140,840 ha (one hundred and forty thousand eight hundred and forty hectares) between the municipalities of Carolina and Estreito and the smaller one with 19,206 ha (nineteen thousand two hundred and six hectares) located between the municipalities of Carolina and Riachão13.

A study by14 points out that the creation of the Chapada das Mesas National Park affected the rural population who lived in the Park area, as their traditionally occupied territory was transformed into a Conservation Unit, restricting their access to the natural resources on which they depended to work and live. Among the activities carried out by these communities are flour mills, artisanal mills, gastronomy with local spices, honey production and popular festivals, which, according to15, translate into an enchanting experience to be interpreted in the Chapada das Mesas National Park. The implementation of the Park’s Management Plan in 2020 led to the adoption of more sustainable practices for the use of natural resources by these communities, strengthening their permanence in their traditionally occupied territories16.

For all the above reasons, the aim of this study is to characterize the land use and land cover of the Farinha river basin and the Chapada das Mesas National Park and its variation over the last 20 years. This characterization is essential for understanding the current state of the basins and for assessing the progress of occupation in the Chapada das Mesas National Park area.

Material and methods

The Farinha river basin is part of the Tocantins River basin and covers an area of 525,579 ha17. Inserted in this landscape is the Chapada das Mesas National Park, which according to18 data described by Martins et al.19, is made up of a geomorphological unit of plateaus and flats of the Farinha River located on the border of the states of Maranhão and Tocantins. According to the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), this area is classified as an Integral Protection Conservation Unit, in accordance with Federal Law No. 9,985/2000, which created the Conservation Unit System20.

The geomorphological composition of the Farinha - MA river basin includes the formation of morrarias sculpted over the years due to the weathering process, giving rise to a relief that has been called “mesetas”, which originate from hardened quartz sandstones formed by the outpouring of volcanic lavas, of the basalt type with the Mosquito and Sambaíba formations21.

In terms of landscape, it is characterized by a set of exuberant relief forms - plateaus - which give this region a scenic aspect of inestimable beauty22. Rocha23describes the region as a water paradise, with its water wealth estimated at around 400 springs. Furthermore, the author, quoting Marques emphasizes that:

“In addition to the volume and existence of numerous watercourses, this area has a very important characteristic which is the color and presentation of the water, which flows in sands that are sometimes red, sometimes whiter, in shades that vary from dark red to yellow orange until they are almost as white and transparent as the water that flows over them. It has a number of aquifer outcrops that are highly valued for their quality and temperature” 24.

Against this backdrop, this study was carried out in the Farinha river basin located between the municipalities of Carolina, Estreito, São Pedro dos Crentes, Feira Nova do Maranhão and Riachão, in the south-western region of the state of Maranhão. The climate is characterized as AW’, according to the Köppen-Geiger classification, with two well-defined seasons: a rainy season from November to May and a dry season from June to October. The relief is characterized as flat / gentle and undulating. According to the digital cartographic base provided by the Ministry of the Environment, the basin has typical Cerrado vegetation. Regarding soils, there is a predominance of quartzarenic neossolo, latossolo yellow, nitossolo vermelho and neossolo flúvico25.

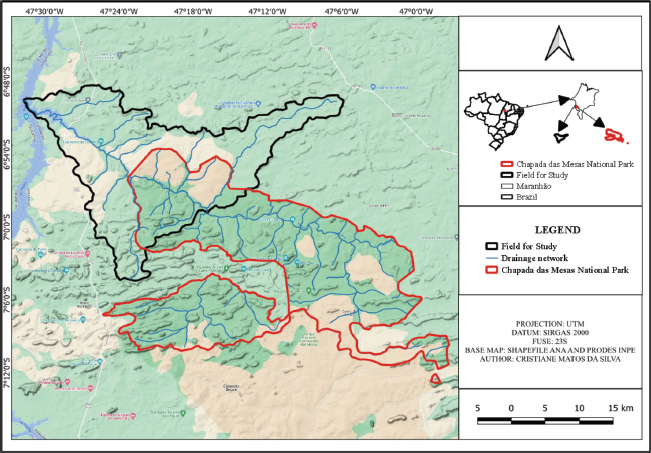

Map 1 shows the details of the Farinha river basin chosen for the study, which corresponds to a fifth hierarchical level basin according to the Ottocoded classification of the National Water Agency with a total area of 55,338.12 ha. This area was chosen because it contains both anthropized and non-anthropized environments and because it is the region where the Farinha River meets the Tocantins River. It is an area considered sensitive to the deposit of sediment carried along the river, which can influence the water quality of both the Farinha and Tocantins rivers. Another factor that has influenced this has been the growth of agroforestry activities, such as forestry plantations, soya plantations and cattle breeding in this region, which is encroaching on the area of the Chapada das Mesas National Park, which has a territorial area of 78,381.62 ha.

Map 1. Study Area of the Farinha River Basin - MA and Area covered by the Chapada das Mesas National Park - Carolina - MA - Brazil

Source: Author, 2023.

To characterize the soil classes of the study area and the Chapada das Mesas National Park, we used the Embrapa Soils shapefile from November 202026 and the Satellite Monitoring and Deforestation in the Legal Amazon Project (PRODES) of National Institute for Space Research (INPE) of Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTIC)27 shapefile for the characterization of the basin’s land use, images and data obtained from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) and the National Institute for Space Research were used, which will be processed in the Qgis 3.16.6 “Hannover” software.

Initially, a study was carried out on the rate of deforestation in the Farinha river basin area and in the Chapada das Mesas National Park area, using satellite images available through the Prodes system28. This system records and quantifies areas larger than 1 hectare that were deforested between 2000 and 2020. The areas deforested from 2000 onwards were discretised into a two-year historical series for the period 2000 to 2012 and an annual series for the years 2013 to 2020. The images were processed using QGIS 3.16.6 “Hannover” software.

To characterise land use and land cover in the Farinha river basin and the Chapada das Mesas National Park area, raster images acquired from the MapBiomas 6.0 library were used for the years 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018 and 2020 in order to characterise land use and land cover in the study area and, by processing the images using Qgis 3.16.6 “Hannover” software, to obtain the areas of each land use and land cover by year. This made it possible to assess the progress of occupation in both areas.

Results and discussion

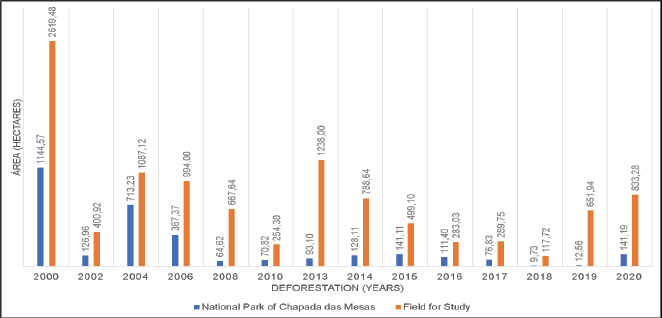

After processing the images extracted from Inpe/Mctic29 , from 2000 to 2020, which show deforestation in areas larger than 1 hectare, Graphic 1 shows that the suppression of native vegetation in the Cerrado biome has been advancing over the years in the Chapada das Mesas National Park area, altering the soil cover in this environmental conservation area.

Graphic 1. Total area deforested in twenty years in the study area and in the Chapada das mesas National Park area

Source: Author, 2023.

Current data from MapBiomas30 reveals frightening figures on the current Brazilian environmental issue, mentioning for example that between 2019 and 2020, only 0.9 % of rural properties deforested in Brazil. However, it is worth highlighting the fact that several areas have already been deforested previously and, if we analyze over a period of 10 or 20 years, we will realise that agribusiness has been settling in areas that were initially forested31.

Corroborating this data, this advance has been comparatively greater in the study area, where deforestation hotspots in the last twenty years have shown a percentage corresponding to 19.89 % of the total area of the basin. While 4.10 % of the total area of the Chapada das Mesas National Park has been deforested over the last twenty years, raising concerns about the maintenance of biodiversity in this Environmental Conservation Unit (Graphic 1).

About the process of recovering these areas, an alarming fact is that there is only a record of some activity in this direction in 2018 and the percentage is derisory at 0.01 % of the total area of the park and 0.06 % of the total area of the river basin. This shows that deforestation has been advancing over the last twenty years in the Farinha river basin and in the Chapada das Mesas National Park.

Data presented by Vasconcellos et al.32 points out that the importance of maintaining soil quality is because its nutrients are one of the first factors to be affected by changes in its use, contributing or not to the fertility of an area. Another very relevant fact about deforestation was reported in the studies by Silva et al.33 and Souza et al.34 which show that changes in soil cover cause erosion and compaction, loss of biodiversity, soil nutrients and others, presenting itself as an unsustainable model with high risks of irreversible changes in the ecosystem, making it difficult to maintain environmental and economic sectors.

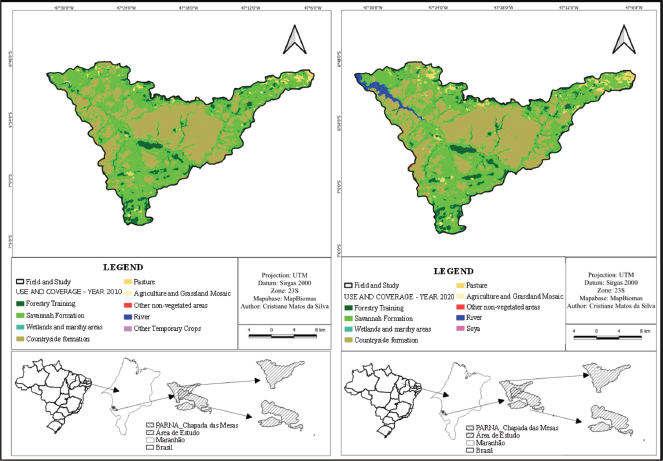

To ascertain the main agents causing environmental changes in the Cerrado ecosystem in the Farinha river basin, maps were generated showing the main uses and coverage of the river basin for the years 2010 and 2020 (Map 2). The percentage areas occupied by natural cover and by each anthropogenic use were then calculated (Graphic 2) in the Farinha river basin.

Map 2. Land Use and Land Cover in the Farinha River Basin - MA in 2010 and 2020

Source: Author, 2023.

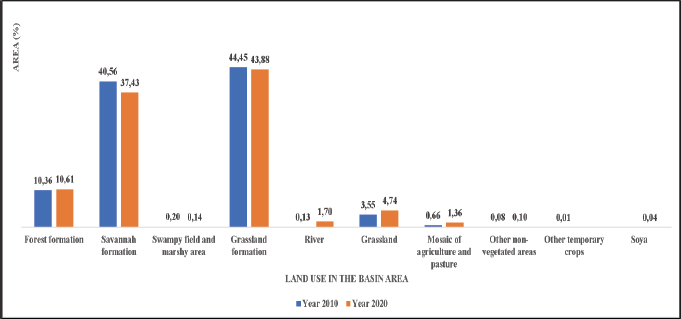

Graphic 2. Percentage of the area in hectares occupied by each type of natural cover in the basin area of the Rio Farinha - MA in the years 2010 and 2020

Source: Author, 2023.

The vegetation coverages known as savannah formation and grassland formation suffered a small variation in the size of their areas between 2010 and 2020, which a priori can be considered normal, since this is an area subject to forest fires due to the dry season that occurs in this region, which runs from May to November. The river area, on the other hand, grew between 2010 and 2020, which can be explained by the presence on the Tocantins River of the Estreito Hydroelectric Power Plant (HPP), which was inaugurated on 17 October 2012 and has been fully operational for 10 years35. It should also be noted that the Farinha river basin is located upstream of this HPP and is therefore influenced by the accumulation of water due to the dam, which may explain this increase in the river’s area.

Silva Borges and Nunes de Oliveira36, in their study of the Meia Ponte River Basin in the state of Goiás, report that the river and lake have increased in size, since the construction of dams to accumulate water for irrigation or hydroelectric use is becoming more frequent, which corroborates the data presented above.

In the basin’s study area, anthropogenic uses have grown significantly, especially pasture areas, which increased by 1.19 % of the total basin area between 2010 and 2020, showing that there is a real advance in livestock farming in the basin area. A similar result is pointed out by Antoniazzi37, where pasture is the anthropogenic use that stands out most in the Cerrado with 61 million hectares (30 % of the total Cerrado area). Annual and perennial crops together occupy 25 million hectares (12.3 %), of which 18 million hectares (8.9 %) are occupied by soya, i.e. the country’s main crop occupies almost 9 % of Cerrado territory. Therefore, the expansion of the agricultural frontier represents the areas where land occupation is advancing and is the main cause of deforestation in the Cerrado38.

In this sense, guided by the concern for environmental conservation and with a view to better characterising the advance of agriculture in the watershed, land use and land cover mapping was carried out in the Chapada das Mesas National Park area and, maps were obtained with the main uses and land cover of the Chapada das Mesas National Park area for the years 2010 and 2020 (Map 3). The areas in hectares occupied by natural cover and by each anthropogenic use (Graphic 3) in the Chapada das Mesas National Park area were then calculated.

Map 3. Land Use and Land Cover in the Chapada das Mesas National Park - MA in 2010 and 2020

Source: Author, 2023.

Graphic 3. Percentage of the area in hectares occupied by each type of natural vegetation cover in the Chapada das Mesas National Park area, MA, in 2010 and 2020.

Source: Author, 2023.

Over the last twenty years, the Chapada das Mesas National Park has shown a balance in the vegetation that makes up the natural land cover (Forest Formation, Savannah Formation, Flooded Field and Marshy Areas and Campestre Formation), demonstrating that its creation has made it possible to maintain the biodiversity of the Cerrado biome.

Hassler39emphasises that protected areas enable the conservation of water resources, scenic beauty, the protection of historical and/or cultural sites, the maintenance of wildlife and air and water quality, as well as providing order for economic and regional growth. Montagna et al.40 emphasise that Conservation Units enable the conservation of genetic diversity and serve as research and experimental sites for improving conservation strategies and the use of genetic resources. And Conservation Units are also an effective way of protecting biodiversity and natural resources, through practices designed to protect biological diversity, guaranteeing the capacity to produce wealth in the long term, especially for Brazil, which has much of its growth justified by the abundance of natural resources41.

In order for this conservation to be maintained, it is necessary to monitor the advance of agribusiness in the area of influence of the Chapada das Mesas National Park, because once agricultural activities are carried out without taking care of good soil and water management practices, they can jeopardize the maintenance of this biodiversity and, consequently, generate losses of nutrients that are essential for the maintenance of this biome.

The results presented in Graphic 3 show that, between 2010 and 2020, there was an increase in land use with pasture in the area of the Chapada das Mesas National Park, equivalent in percentage terms to 0.23 % of the total area of the Chapada das Mesas National Park, which emphasises the concern about the possible deforestation of areas of the Chapada das Mesas National Park Conservation Unit. Corroborating the results presented above, the study by Silva42 reports that although many environmentalists understand that the practice of food production by the Park’s traditional communities using swiddens to plant some crops has caused negative impacts on the conservation area, it was realised that the expansion of agribusiness has intensified and accelerated the process of deforestation in the southern region of Maranhão.

According to data from the Ministry of the Environment43 presented by Mourão; Lino44, in addition to the environmental aspects, the cerrado also contributes to the social issue, as populations survive on its natural resources, including indigenous ethnic groups, riverbank dwellers, babaçueiras, vazanteiros and quilombola communities that together form part of the historical and cultural heritage, generating traditional knowledge of its biodiversity.

Data presented by Silva; Araújo; Conceição45 highlights that cattle farming in the Chapada das Mesas National Park by the communities that live there has been causing ecological damage to the region for years and, even with the adoption of management techniques, such as the controlled use of fire for grazing, these, according to the authors, are still not enough to avoid the negative impacts on the Conservation Unit.

According to Mourão; Lino46, the increase in agribusiness in the Cerrado is fuelling deforestation and the destruction of its natural resources, because to increase production, more land is needed for planting. Also, according to the authors, the period from 2000 to 2019 saw accelerated agricultural expansion, especially driven by the rise in exports and the modernisation of domestic production. However, because of this agricultural expansion, environmental impacts are intrinsic to the area of agricultural activity due to the use of mechanised techniques and intensive use of agrochemicals.

In this sense, although the Chapada das Mesas National Park has a Management Plan for the use of its area, an intense evaluation of the techniques used by cattle farmers must be carried out to prevent the advance of grazing from intensifying the loss of biodiversity, soil and water contamination and the loss of nutrients, which can be carried into the Farinha river, generating an environmental impact in this region.

Conclusion

This advance brings with it the possible loss of the Cerrado’s biodiversity, the possible silting up of the river, which is already suffering from the impact of the opening and closing of the Estreito - MA hydroelectric dam gates, as well as the loss of soil and nutrients if anthropic activities do not use conservation measures, such as directing drainage water, planting on contour lines, using terracing and other measures.

Land use in the Farinha river basin and in the Chapada das Mesas National Park over the last 20 years has shown an increasing level of intensification of agribusiness activities, especially pasture, which corroborates the data presented in the Annual Report on Deforestation in Brazil published by MapBiomas in 2020.

If we consider that this intensification can lead to losses of water, soil, and nutrients, and that these can be carried into the channel of the Farinha river, it is of the utmost importance to quantify what these nutrients are and how much is lost.

To this end, studies of rainfall intensity, rainfall erosivity and quantification of the physical and chemical parameters of the water are of the utmost importance because they make it possible to elucidate the variables exposed by the intensification of deforestation in the Farinha River basin region. These quantifications make it necessary to propose mitigating measures to minimize environmental impacts both in the Farinha river basin area and in the Chapada das Mesas National Park area.

References

ANA – Agência Nacional de Águas. 2019. Outorga para aproveitamento hidrelétrico – DRDH.

Annual Report on Deforestation in Brazil. 2020. Relatório Anual do Desmatamento no Brasil. https://storage.googleapis.com/alerta-public/dashboard/rad/2022/RAD_2022.pdf

Bolwerk, Diógenes & Ertzogue, Marina. 2020. “Mudanças climáticas e/ou mudanças socioculturais na Amazônia Legal”. Revista Ibero-Americana de Ciências Ambientais, 12, 202-213. https://doi.org/10.6008/CBPC2179-6858.2021.001.0017

Brasil. 2000. Lei nº 9.985, de 18 de julho de 2000. Dispõe sobre o Sistema Nacional de Unidades de Conservação.

Brasil. 2005. Decreto s/n, de 12 de dezembro de 2005. Cria o Parque Nacional da Chapada das Mesas, nos Municípios de Carolina, Riachão e Estreito, no Estado do Maranhão, e dá outras providências. Brasília.

Brasil. 2023. Ministério do Meio Ambiente e Mudança do Clima. Plano de ação para prevenção e controle do desmatamento e das queimadas no bioma cerrado (PPCerrado): 4ª fase (2023 a 2027) [recurso eletrônico] – Brasília: MMA.

Dias, P. A. 2016. Nota Técnica 001/2016-PNCM. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade. Parque Nacional da Chapada das Mesas. Carolina.

Embrapa – Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária. 2022. Mapa de Solos do Brasil. http://geoinfo.cnps.embrapa.br/layers/geonode%3Abrasil_solos_5m_20201104#more

Embrapa – Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária. 2024. O que é Matopiba?. https://www.embrapa.br/tema-matopiba/perguntas-e-respostas

FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2015. Las amenazas a nuestros suelos. 2015. http://www.fao.org/resources/infographics/infographics-details/es/c/326259/

FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2019. Soil and Water, http://www.fao.org/land-water/land/en/

França, Daniela de Azeredo; Ferreira, Nelson Jesus. 2005. Considerações sobre o uso de satélites na detecção e avaliação de queimadas. Anais. XII Simpósio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto, Goiânia, INPE, 3017-3023.

Hassler, Márcio Luís. 2005. “A importância Das Unidades De Conservação No Brasil”. Sociedade & Natureza, 17(33), 79-89. https://doi.org/10.14393/SN-v17-2005-9204

IBGE- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. 2006. Mapa de Unidades do Relevo do Brasil. Escala 1:5.000.000.

IBGE- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. 2011. Geomorfologia: mapa geomorfológico do estado do Maranhão. Rio de Janeiro.

ICMBio – Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade. 2020. Plano de Manejo do Parque Nacional da Chapada das Mesas. Brasília.

Imazon– Instituto do Homem e Meio Ambiente da Amazônia. 2021. Boletim do desmatamento da Amazônia Legal (Junho 2021) SAD. https://imazon.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/SADjunho2021.pdf

Manetta, Bárbara Romano; Barroso, Bruna; Arrais, Tallicy; Nunes, Thays. 2015. “Unidades de Conservação”. Engenharias on-line, 1(2).

Marques, Ana Rosa. 2012. Saberes geográficos integrados aos estudos territoriais sob a ótica da implantação do Parque Nacional da Chapada das Mesas, sertão de Carolina – MA. Tese (Doutorado) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geografia da Universidade Estadual Paulista, Campus de Pres. Prudente.

Martins, Fernanda Pereira; Salgado, André Augusto Rodrigues; Barreto, Helen Nébias. 2017. “Morfogênese da Chapada das Mesas (Maranhão-Tocantins): paisagem cárstica e poligenética”. Revista Brasileira De Geomorfologia, 18(3), 623-635. https://doi.org/10.20502/rbg.v18i3.1180

MMA - Ministério do Meio Ambiente. 2017. O Bioma Cerrado. http://www.mma.gov.br/biomas/cerrado.

Miranda, Evaristo Eduardo de; Magalhães, Lucíola Alves; Carvalho, Carlos Alberto de. 2014. Proposta de delimitação territorial do Matopiba. Nota Técnica 1. Embrapa, Campinas - SP.

Montagna, Tiago; Ferreira, Diogo Klock; Steiner, Felipe; Santos da Silva, Fernando André Loch; Bittencourt, Ricardo; Silva, Juliano Zago da; Mantovani, Adelar; Reis, Maurício Sedrez dos. 2012. “A Importância das Unidades de Conservação na Manutenção da Diversidade Genética de Araucária (Araucaria angustifolia) no Estado de Santa Catarina”. Biodiversidade Brasileira, 2(2), 17-24. https://doi.org/10.37002/biodiversidadebrasileira.v2i2.270

Monteiro, Daniel Macedo Lopes Vasques. 2022. “Processos de espoliações no Brasil atual: Ofensivas do agronegócio sobre os direitos ambientais territoriais”. Revista Tamoios, 18(1), 75-95. https://doi.org/10.12957/tamoios.2022.63317

Moura, Raylane Silva; Silva Coelho, Leonardo Oliveira da, Fernandes, Louize Nascimento, Rogério Taygra Vasconcelos; Oliveira, Jônnata Fernandes de. 2021. “Impactos causados pela implantação do Parque Nacional da Chapada das Mesas em Carolina, Maranhão”. Acta Tecnológica, 15(2), 11-26. https://doi.org/10.35818/acta.v15i2.806

Mourão, Rildo; Lino, Estefânia Naiara da Silva. 2021. “Expansão agrícola no Cerrado: o desenvolvimento do agronegócio no estado de Goiás entre 2000 a 2019”. Caminhos de Geografia, 22(79), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.14393/RCG227951217

Nobre, Nathália Coelho; Silva, Cristiane Matos da; Santana, Jhonata Santos; Silva, Wilson Araújo da. 2020. “Caracterização morfométrica, climática e de uso do solo da Bacia hidrográfica do rio Farinha – MA”. Acta Iguazu Cascavel, 9(1), 11-34. https://doi.org/10.48075/actaiguaz.v9i1.19021taiguazu/article/view/19021/15374

Pena, Rodolfo F. Alves. 2017. Fronteira Agrícola no Brasil. http://alunosonline.uol.com.br/geografia/fronteira-agricola-no-brasil.html

Pires, José Salatiel Rodrigues; Santos, José Eduardo dos; Del Prette, Marcos Estevan. 2002. “A utilização do conceito de bacia hidrográfica para a conservação dos recursos naturais”, en Schiavetti, Alexande; Camargo, Antonio F. M. (Eds.), Conceitos de bacias hidrográficas: teorias e aplicações., Ilhéus, Editus, 17-35.

PRODES (INPE/MCTIC). 2020. Supressão da vegetação nativa para o bioma Cerrado à partir de 2000 (Raster). Divisão de Processamento de Imagens - DPI/OBT/INPE. http://terrabrasilis.dpi.inpe.br:/geonetwork/srv/api/records/333db098-86ec-4447-a8b8-067ae94a2329

Resende, Fernanda Cristina; Soares, Tereza Beatriz Oliveira; Santos, Paula Resende; Pereira, Gabriel. 2015. “Análise De Índices Espectrais Para Estimativa De Áreas De Regeneração Florestal No Parque Nacional Chapada Das Mesas”. Revista Territorium Terram, 3(5), 95-104. http://www.seer.ufsj.edu.br/territorium_terram/article/view/1053/856

Rocha, Danielly Morais. 2016. Entre os morros e as figuras: gravuras rupestres no Parque Nacional Chapadas das Mesas, Carolina, Maranhão. Dissertação (Pós-Graduação em Arqueologia) - Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Laranjeiras, SE.

Santos, Leovigildo Aparecido Costa; Vieira, Lais Marques Fernandes; Martins, Patrick Thomaz de Aquino; Ferreira, Anamaria Achtschin. 2019. “Conflitos de Uso e Cobertura do Solo para o Período de 1985 a 2017 na Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Caldas-GO”. Fronteiras Journal of Social, Technological and Environmental Science, 8(2), 189-211. https://doi.org/10.21664/2238-8869.2019v8i2.p189-211

Silva, Cristiane Matos da. 2019. Análise dos conflitos pelo uso da água na bacia hidrográfica do médio Tocantins. Dissertação (Mestrado em Engenharia de Barragem e Gestão Ambiental) - Núcleo de Desenvolvimento Amazônico em Engenharia, Universidade Federal do Pará, Tucuruí.

Silva, Cristiane Matos da; Teixeira, Otávio Noura; Ishihara, Júnior Hiroyuki. 2022 “Uso da Teoria dos Jogos como ferramenta para identificação e mitigação de conflitos pelo uso da água na área de abrangência da UHE Estreito – MA- Brasil”, Água y Territorio / Water and landscape, 21, 121-133. https://doi.org/10.17561/at.21.5896

Silva, Maria Lindalva Alves da. 2017. Percepção ambiental dos moradores da Chapada das Mesas sobre a criação do Parque Nacional, Maranhão, Brasil. Dissertação (Mestrado em Biodiversidade, Ambiente e Saúde), Centro de Estudos Superiores de Caxias, Universidade Estadual do Maranhão.

Silva, Maria Lindalva Alves da; Araujo, Maria de Fátima Veras; Conceição, Gonçalo Mendes da. 2019. “Síntese histórica E Socioambiental Do Parque Nacional Da Chapada Das Mesas (MA)”. Revista Brasileira De Ecoturismo (RBEcotur), 12(2), 170-188. https://doi.org/10.34024/rbecotur.2019.v12.6724

Silva, Maria Lindalva Alves da; Araujo, Maria de Fátima Veras; Conceição, Gonçalo Mendes da. 2020. “Parque Nacional da Chapada das Mesas (Maranhão/Brasil): atividades socioeconômicas dos moradores e seus reflexos”. Revista Ibero-Americana de Ciências Ambientais, 11(2), 381-392. https://doi.org/10.6008/CBPC2179-6858.2020.002.0035

Silva Borges, Vinícius; Nunes de Oliveira, Wellington. 2021. “Análise Multitemporal do Uso e Cobertura do Solo da Bacia Hidrográfica do Rio Meia Ponte”. REEC Revista Eletrônica de Engenharia Civil, 17(1), 79-93. https://revistas.ufg.br/reec/article/view/68192/37681

Souza, Gabriel Henrique de Olanda; de Lima, Rafael; Rosseto, Victoria; Aparecido, Lucas Eduardo. 2021. Correlação entre a dinâmica do desmatamento e pastagem nos municípios prioritários do bioma Amazônia no estado do Pará. Anais do IV Seminário de Agroecologia/III Seminário de educação do Campo do IFPE/Org.: Gonçalves, Andre Luis; Silva, Camila Lima da. Recife: IFPE. https://portal.ifpe.edu.br/wp-content/uploads/repositoriolegado/portal/documentos/anais_2021_-ifpe-_final_version.pdf

Sudré, Stephanni; Souza, Thais Vieira de; Oliveira, Andressa Nogueira de; Azevedo, Camilo da Silva. 2020. “Percepção Da Comunidade Local Sobre O Turismo No Parque Nacional Da Chapada Das Mesas, Carolina (MA)”. Revista Brasileira De Ecoturismo (RBEcotur,) 13(2), 293-309. https://doi.org/10.34024/rbecotur.2020.v13.6749

Vasconcellos, Renan Coelho de; Beltrão, Norma Ely Santos; Martins, Soraya Souza; de Paula, Manoel Tavares. 2020. “Identificação de Serviços Ecossistêmicos na Produção Agrícola: Um Estudo em Sistemas Agroflorestais”. Research, Society and Development, 9(10), e9259109268. https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v9i10.9268

WWF – Brasil. 2020. Desmatamento no Cerrado aumenta 13 % e bioma perde 7,3 mil km² de vegetação nativa. https://www.wwf.org.br/?77608/cerrado-prodes-desmatamento-aumenta-123-perde-73-mil-km2

_______________________________

3 Bolwerk; Ertzogue, 2020, 208.

4 Brasil, 2023, 17.

9 Miranda; Magalhães; Carvalho, 2014, 2.

10 Santos et al., 2019, 190.

11 Pires et al., 2002, 19. Santos et al., 2019, 190.

12 França; Ferreira, 2005, 3018. Resende et al., 2015, 96.

13 Dias, 2016. Brasil, 2005; Sudré et al., 2020, 302.

14 Moura et al.,2021, 21-22.

15 ICMBIO, 2020,12.

16 Silva; Conceição; Araújo, 2020, 382.

17 Nobre et al., 2020, 13.

19 Martins et al., 2017, 624.

20 Brasil, 2000. Silva; Araújo; Conceição, 2019, 180.

21 IBGE, 2011. Silva; Araújo; Conceição, 2019, 171.

22 Matins et al., 2017, 624.

23 Rocha, 2016, 57.

24 Marques, 2012, 51,52.

25 MMA, 2017. Nobre et al., 2020, 14.

30 Annual Report on Deforestation in Brazil, 2020.

31 Monteiro, 2022, 79-80.

32 Vasconcellos et al., 2020, 8.

33 Silva et al., 2019, 126.

34 Souza et al.,2021, 64.

35 ANA, 2019. Silva, 2019, 70. Silva; Teixeira; Ishihara, 2022, 124.

36 Silva Borges; Nunes de Oliveira, 2021, 89.

37 Antoniazzi, 2021, 13.

38 Pena, 2017. Mourão; Lino, 2021, 3.

39 Hassler, 2005, 85.

40 Montagna et al., 2012, 23.

42 Silva, 2017, 83-84.

43 Ministério do Meio Ambiente, 2017.

44 Mourão; Lino, 2021, 3.

45 Silva, Araújo; Conceição, 2020, 385.

46 Mourão; Lino, 2021, 4.