RE-ARTICULATION IN ZORA NEALE HURSTON’S THEIR EYES WERE WATCHING GOD

Divya Sharma

RE-ARTICULATION IN ZORA NEALE HURSTON’S THEIR EYES WERE WATCHING GOD

The Grove, vol. 30, 2023

Universidad de Jaén

REARTICULACIÓN EN SUS OJOS MIRABAN A DIOS DE ZORA NEALE HURSTON

How to cite

:

Sharma, Divya. “Re-articulation in Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God.” The Grove. Working Papers on English Studies, vol. 30, 2023, pp. 89-118. https://doi.org/10.17561/grove.v30.7895

Received: 10 April 2023

Accepted: 13 september 2023

Abstract: Zora Neale Hurston’s most acclaimed novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), juxtaposes the sensuous side of ecology with that of female sexuality and sensuousness, through the epiphany of the blossoming pear tree. The present research article explores this idea to establish Zora Neale Hurston as a womanist who anticipates ecofeminism and ecosexuality creating a female protagonist who finds a voice narrating her story.

Keywords: Ecofeminism; Womanism; Zora Neale Hurston; Queer Ecofeminism; Deep Ecology; Ecosexuality.

Resumen: La novela más aclamada de Zora Neale Hurston, Sus ojos miraban a Dios (1937), yuxtapone el lado sensual de la ecología con el de la sexualidad y la sensualidad femeninas, a través de la epifanía del peral en flor. El presente artículo de investigación explora esta idea para establecer a Zora Neale Hurston como una mujerista que anticipa el ecofeminismo y la ecosexualidad creando una protagonista femenina que encuentra una voz narrando su historia.

Palabras clave: Ecofeminismo; Mujerismo; Zora Neale Hurston; Ecofeminismo Queer; Ecología Profunda; Ecosexualidad.

“Earth itself has become the nigger of the world.”

—Alice Walker

1. Introduction

“That a great mass of Negros can be stirred by the pageants of Spring and Fall; the extravaganza of summer, and the majesty of winter…is ruled out,” complains Zora Neale Hurston in her essay, “What White Publishers Won’t Print” (169-73). Her statement calls for inclusiveness in the nature writing. While aspects of nature writing such as the transcendentalist theory or the American Naturalist theory have stood as White-male and Christian, ecocriticism and ecofeminism bear witness to inclusiveness and intersectionality. In the light of such an understanding it is imperative to undertake multi-cultural analysis of Hurston’s work. Traditionally ecofeminism and womanism are two distinct forms of feminisms and do not associate with each other. And Hurston has never been interpreted from the standpoint of ecofeminism. However, ecofeminists and women of colour have had significant, though failed, interactions in the past.

1.1. Experience of Women of Colour with Ecofeminism

1.1.1. WomenEarth

WomanEarth is the link between the feminist anti-militarism of 1970s and the ecofeminism of the 1980s. A series of activist actions that identified the interconnections between patriarchy, militarism, social justice, and ecology began to be called ecofeminism in early 1980s. Ynestra King at this time thought that what was needed was an “ecofeminist educational institution that could provide resources for ecofeminist action, engage in networking, and support research on relevant issues” (Sturgeon 81). And that such an institution was to have as its central concern—anti-racism (something she realized observing the racism within the ‘Women and Earth Conference’ and ‘Women’s Pentagon Actions.’ These visions she shared with Starhawk with whom she discussed about the organization of the Feminist Peace Institute from 1984-85 and which finally was established in 1985. The solution King thought of as to counter racism was through coalitions and multi-racial organizations but she did not want to outreach the women of color as if they were in the periphery so she sought advice from Barbara Deming who suggested her to meet Barbara Smith. King met Smith in March 1986. Smith advised her the principle of “racial parity” which meant that “there would be an equal number of White women and women of colour within the organization, particularly within the decision-making structures” (Sturgeon 79). So, the WomenEarth Feminist Peace Institute was formed in 1986. Following the principle of racial parity the core decision making members of the organization were equally divided, four of them were women namely, Rachel Bagby, Popusa Molina, Rachel Sierra, and Luisah Teish, while the other four were White namely, Gwyn Kirk, Ynestra King, Margie Mayman, and Starhawk.

The Phases of the Organization in terms of the Issue of Racial Parity

Feminist Peace Institute—Till the time King had met Smith in March 1986 the institute was more in terms of international than racial diversity.

WomenEarth Feminiat Peace Institute—From the time of King’s meeting with Barbara Smith in March 1986 up till the Hampshire gathering from August 17 to 23 in 1986 there remained a constant attempt at the resolution of the contesting issues of international diversity and racial parity, and several moments of arguments and contention occurred.

WomenEarth II—From September 1986 to August 1989 the office was shifted and efforts were focused towards creating a model of antiracist ecofeminism which finally all ended on August 10, 1989 at Ynestra King’s desk, a time when ecofeminism was flourishing.

Why did the collaboration fail?

-

It came across as a White woman’s moment to the women of colour. Its beginning was the Feminist Peace Institute and even though it was reshaped as the WomanEarth Feminist Peace Institute its agendas remained as handed over.

-

The genesis of the movement was with two White women, namely, Ynestra King and Starhawk.

-

Within the movement the trust was being given to the issues of international diversity (namely because of the wealthy White woman who patronized the cause) rather than racial parity, the issue that formed the base of WomenEarth coming together.

-

The decision making process that was an “informal consensus process” or “the collective and egalitarian” in nature proved insignificant for “there were inequalities…mostly stemming from King and Starhawk’s previous work on the project, their relationship to the funder, and King’s day-to-day financial responsibility” (Sturgeon 93).

-

The very idea of racial parity as a means of resolving the issue of racism within the structure of the organization ended replicating the dichotomy of lack and privilege that white and non-white asserted, only this time it was color and no color.

As a moment that took pride in its anti-racist character WomanEarth was probably its only and most formal bid at satisfying its ego but the effort turned in vain.

1.2. Cross Connections between Womanism and Ecofeminism

-

Both womanists and the ecofeminists recognize the systems of oppression as interconnected. A black feminist Patricia Hills Collins enlists two works, namely, Angela Davis’s Women, Race and Class (1981) and Andre Lorde’s (1984) classic volume, Sister Outsider that establish with the idea. In an essay entitled, “Toward a Politics of Empowerment” included in her Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (2009), Collins asserts that domination encapsulates within the tools of—structural, disciplinary, hegemonic, and interpersonal domains of power. These remind of Warren’s detailed exploration of the dynamics of unjust domination and oppressions in the Ecofeminist Philosophy (2000). To briefly explain, the structural domain of power encompasses how social institutions are organized to reproduce black women’s subordination and the subordination of the multiple “Others.” The disciplinary domain of power (reminds of Foucault) operates not through explicit racist or sexist social policies but through “bureaucratic hierarchies and techniques of surveillance” (Collins 299). The hegemonic variant writes Collins operates through school curricula, religious teachings, community cultures, family histories and the mass media in validating unjust oppressions of non-dominant groups. Lastly, the interpersonal domain of power operates in bringing domination by replacing, “...cultural ways of knowing with...hegemonic ideologies that...justify practices of other domains of power” (Collins 306).

-

Françoise de Eaubonne talks of sexual control (cause of overpopulation) and the control on production (cause of surplus production) by man—these issues are echoed even in the U. S. black feminist thought. A black feminist chronicles, while White women were: ...assigned the duty of reproducing the national group’s population...U. S. population policies broadly defined, aim to discourage Black women from having children, claiming that black women make poor mothers and that their children end up receiving handouts from the state...White women are encouraged to increase their fertility...assisted by...technologies...fertility of undocumented women of color is seen as a threat...especially if such women’s children gain citizenship and apply for public services...(Collins 249).

-

Both recognize the social constructedness of the negative images of women. Where ecofeminists like Mary Daly talk of “Hags” and “Crones” in her Gyn/Ecology, Patricia Collins talks of the “matriarchs” and “welfare mothers” (Collins 92).

-

Both ecofeminists (even though some amongst them try to distance themselves from it all ecofeminist positions lapse into it eventually) and Black feminists are charged of being essentialists, focusing on women’s physiological and social experiences. Both qualify under the category of “essentialism per se” if one was to judge according to Kathy Ferguson’s categorization of essentialisms in her The Man Question: Visions of Subjectivity in Feminist Theory (1993).

-

Both hold a holistic view of nature and are sensitive to environmental ethics‟ third theory i.e. an ecocentric view of nature that the environment has an intrinsic value and has its rights as much as any other part of the creation. The first two theories hold an anthropocentric view that man has the moral responsibility towards environment and animal life because of his sense of reason.

-

Even though both celebrate the affinity of women to nature both are aware of the social constructivist aspect of it as well.

-

Both cultural ecofeminists (like Mary Daly) and certain womanists (like Alice Walker herself) seek answers in spiritual alternatives Brammer, the fourth dimension, and a pleading for inclusiveness.

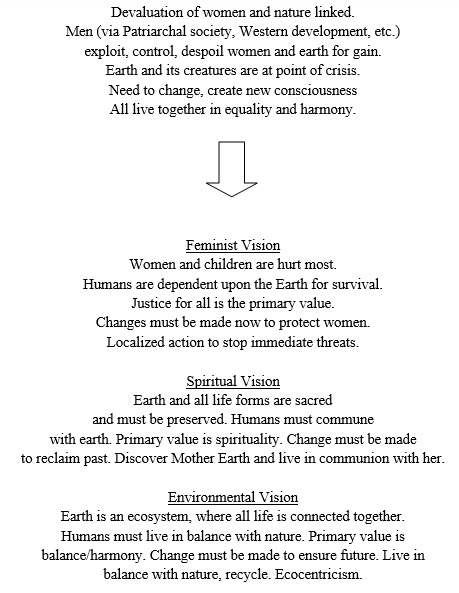

Let us briefly delve into this characteristically peculiar quality of ecofeminism while we try to understand and further develop Brammer’s vision of ecofeminism. Leila R. Brammer’s paper “Ecofeminism, the Environment, and Social Movements,” presented at the National Communication Association 1998 Convention held at New York, offers an interesting rhetorical analysis of ecofeminism, redefining what a “movement” means. The basic premise that Brammer builds on is that ecofeminism is a social movement. However, it must be noted that this rhetorical structure is based on the ideas expressed in the collection, Reweaving the World: The Emergence of Ecofeminism, assembled by Irene Diamond and Gloria Feman Orenstein. Brammer gives a three vision rhetorical model of ecofeminism to which I add some new dimensions.

Figure 1

SAGA

2. An Exploration of Hurston’s Ecofeminist Sensibility

“…Life is evolving to an Omega Point of oneness and love.”

—Teilhard de Chardin’s words as quoted by Larry Withhaam in a newspaper article “Gaia Addressess Science, Faith, New Age: Today’s Event Unites Man’s Consciousness with the Living Earth” for The Washington Times (Jan. 23, 1997:2)

As one takes a tour de force into the celebrated works of Zora Neale Hurston one encounters tender sensitivity towards nature, contrary to the commonly held myth of her times. The general opinion was that African Americans could not be environmentalists. Scott Hicks in his essay, “Zora Neale Hurston: Environmentalist is Southern Literature,” quotes a sociologist, namely, Robert Emmet Jones’ statement from a journal article, “Blacks Just Don’t Care: Unmasking Popular Stereotypes about concern for the Environment among African Americans” that, “…one common assumption is that Blacks are rather shallow in their support for environmental protection” (113), an assumption that Jones himself debunks. Hicks further goes on to tell how the environmental statistics of the time pointed a low participation of African Americans in the National Park Service and a low rate of visitations. But it seems that the official statistics strategically missed that this:

…whitenesss of the American wilderness…[was] materially and discursively produced. Rifles, nooses, and bloodhounds ensure that Native Americans, African Americans, and even poor whites were removed from and barred to state parks, hiking trails, hotels for weekend retreats, and so forth that dotted and defined the American wilderness. (Starkey 6)

Socially constructed myths such as this often find expression in the texts of the times and percolate to the minds of the post-generations. Identical is with those who argue against Hurston qualifying as an environmentalist, through the aid of following arguments, as summarized by Scott Hicks, who himself holds her as an environmentalist. It is believed that being an African American her sensibility towards nature is a predetermined fact. Secondly, her sex becomes a significant issue, for a black female in her doubly colonized status is rendered voiceless, leaving little room for lending a voice for any cause—here nature. The female herself is placed with nature within the culture/nature dualism. As ecofeminists have shown, Cartesian dualism “segregates culture from nature, man from woman” and thus affects “the feminization of nature,” a process that devalues women and “legitimizes the detrimental exploitation of both women and nature” (Cheng-Levine 369). The conflation of women and nature, ecofeminists demonstrate, seeks to render the female subject mute and prone to masculine exploitation and extraction. Thirdly, Hurston is a Southerner, even though she hails from an all black town of Eatonville, her status is of the “Other” in contrast to the standard-landscape of the United States. The swamps of her hometown were held inferior to the West’s aridity.

Yet, in spite of these speculations, Hurston’s work evidently reveals her environmental consciousness. The ecological surroundings she grew in as a child, find expression in her works in the minutest detail. Hurston’s proximity with nature is explicit when she writes in the Dust Tracks on a Road:

We live on a big piece of ground with two chinaberry trees shading the front gate…cape jasmine bushes with hundreds of blooms on either side of the walks. I loved the fleshly, white, fragrant blooms as a child….There were plenty of orange, grapefruit, tangerine, guava, and other fruits in our yard. (11-12)

Her deep association with the oak tree during her forming years is also indicative of the love she felt for nature and all life. She re-lives the experience in the Dust Tracks :

I was only happy in the woods, and when the ecstatic Florida spring time came strolling from the sea, trance—glorifying the world with its aura….I hid out in the tall wild oats that waved like a glinty veil….I nibbled sweet oat stalks and listened to the wind soughing and sighing through the crowns of the lofty pines. I made particular friendship with one huge tree and always played about its roots. I named it “the loving pine,” and my chums came to know it by that name. (41)

Hurston’s act of giving a name to her favourite oak tree is an aide-memoire to a similar idea one comes across in the research work of the widely celebrated wildlife conservationist Jane Goodall. Jane Goodall is a British, primatologist, ethnologist, anthropologist, and UN Messenger of Peace. She is the world’s foremost expert on chimpanzee social and family life, without a collegiate training, she observes things that strict scientific doctrines overlook. She, in her research, instead of numbering chimpanzees she dealt with, gave them names such as “Fifi” and “David Greybeard.” Her research bears witness to the fact that even animals have individual personalities and are capable of emotions and rational thought, a finding that baulks the myth of anthropocentricism or “Man the Toolmaker.” It is interesting to note how her mother Vanne Morris-Goodall, a novelist herself, initiated Jane’s love for animals as a child, buying her a chimpanzee toy, naming it “Jubliee” much to the horror of her friends. The symbolism of the act is quite significant for we see a mother initiating her daughter into further love of humanity and all life.

The rich imagery that Hurston creates throughout her work portrays a reasonably fair economic standard for her family, contrary to the general assumption that African Americans were incapable of such a way of life. The issue of course remains contestable, for some question the reliability of her autobiography and the credibility of the then existent government departments, while others like Scott Hicks, an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Carolina and an expert in the field of African American and Environmental Literature, rebut pamphlets like the United States Department of Agriculture’s published, “Negro Families Can Feed Themselves” (1942), and Richard Wright’s chronicled history in the 12 Million Voices (1941). Hurston’s imagery offers a picture where nature is a “nurturer.”

Hurston’s observation of the nature is that of a keen observer, she is aware of the plunder that the nature is subjected to. Her perspective is that of an ecological “activist” who tries to raise issues infesting the earth caught in the era of the anthropocene, through her writings. Certain remarks of hers ascertain the point. She states in her autobiography, “Negroes were found to do the clearing. There was the continuous roar of the crashing of ancient giants of the lush woods, of axes, saws and hammers” (3). Her critique of the turpentine and timber industries, of repeated deforestation, and consequent soil erosion and floods is to an accompaniment of other issues like the unprecedented growth in the fields of science and technology at the cost of nature. Her work even bears witness to her concern for animal conservation and recognition of the issues of environmental justice. Her sensitivity is reflected through her statements, when she writes, “Their wealthy homes, glittering carriages behind bloodied horses…occupied by well-dressed folk, presented a curious spectacle…” ( Dust Tracks 4). “…I was not afraid of snakes. They fascinated me…in a way…I still cannot explain. I got no pleasure from their death” ( Dust Tracks 41). The overall spectacle of this time included rapid transformations—from wilderness to pastoral landscapes, and from pastoral to timber industry, a sequence of activity that marked excessive degradation of soil and deforestation. A process that corresponded with the transitions from slavery to sharecropping and from sharecropping to wage labor for all blacks in America. Thomas Barbour chronicles in his That Vanishing Eden: A Naturalist’s Florida (1944), rampant ditching, drainage, and deforestation for farming and development in Florida that was ongoing.

Hurston had a pantheistic view of God like many other black feminists. Alice Walker, a womanist locates the divine within the “color purple.” Tuzyline Jita Allan summarizes the vie quite aptly, “With the intensity of a Romantic, Walker has managed to turn the idea of the unity of nature into a personal religion…[her] neo-pantheistic message of the ‘world God’ and ‘full humanity’…[is] a state of oneness with all things”…(128-29). In her conception God is transcendent. She rejects the scriptural notion of a white God. She seems to conform:

…I do not pray….It is simply not for me….The springing of the yellow line of morning out of the misty deep of dawn, is glory enough for me. I know that nothing is destructible; things merely change forms. When the consciousness we know as life ceases, I know that I shall be part and parcel of the world….The stuff of my being is matter, ever changing, ever moving, but never lost;…(Dust Tracks226).

The comment establishes Hurston’s holistic view of life. She advocates an alternative spirituality as a means of resistance to both the patriarchal sexist interpretations of God, as resisted by the “white’ ecofeminists, while simultaneously resisting the racist politics of the “imposed” religion on the blacks.

Zora Neale Hurston was born in Notasulga, Alabama, as the fifth of the eight children, to John Hurston (a carpenter and Baptist preacher), and Lucy Potts Hurston (a school teacher). The security and domestic bliss of a normal childhood were not in stored for her. Her mother passed away when she was nine, and her father who failed to understand her, was a philanderer, drenched in the social structures of the society he breathed in. Her academic training took place in the Morgan Academy, Baltimore (1917-18) and Howard Prep School, Washington, DC (1918-19). She also attended the Howard University where she received an Associate Degree in 1920. Her anthropological study, however, was with Franz Boas at the Barnard College. Franz Boas, Mark Helbling enumerates depicts a mature conception of anthropology that is evident in Hurston’s anthropological work. Helbling enlists Boas’s attack on, “…the scientific racism that serves to legitimize discrimination in America and…the emphasis on history to challenge evolutionary theories used to argue for the biological inferiority of African Americans” (160). Hurston’s work too serves the same objectives. She advocates addressing the issue of race through embracing of one’s own cultural roots (in Africa), to resist the Western subordinating influences. She was for an overall upliftment of her people irrespective of gender.

Hurston’s ecocentric appreciation of the inter-penetrations of the human and the wild, culture and nature, take root in her childhood. As a child she was surrounded by natural richness. “There were plenty of orange, grapefruit, tangerine, guavas and other fruits in our yard,” she writes in her autobiography, Ensconced in surfeit and protected by community, Hurston is free to enjoy “the mocking birds [that] sang all night in the trees [and a]lligators [that] trumpeted from their strong hold in Lake Belle” (Dust Tracks 584). The wild and the tame, in other words, coexist in harmony.

She sees herself not as a settler, colonist, or pioneer, someone who sees wilderness as ungodly or dangerous or nature as separate, divisible, and thus conquerable. Instead, she sees herself as but one of many parts in a complex community, as someone who listens to and learns from all living things. Her own maturation, she writes, finds its analogy in nature: she grows like “a gourd vine, and yelling bass like a gator” (Dust Tracks 579).

If one was to delve deep into the charges often held against her political position of opposing the communist party in the late forties and early fifties and especially her essays, “A Negro Voter Sizes Up Traft” that appeared in the December 8 issue of the Saturday Evening Post, “Why the Negro Won’t Buy Communism,” that appeared in June 1951, in the American Legion Magazine, or her well known opposition of the 1954 Supreme Court desegregation, one observes an opposition of a strategic subordination that these social-system-tools had the potential to impose through a creation of a dualistic vent of White and Black, in the manner colonial policy of white man’s burden dwelled. This awareness of the subordination tactics is also reflective of her ecofeminist sensibility. For even though she holds a somewhat similar stance as the ‘spiritual’ ecofeminists, she cannot be charged of escapism because of her political outlook, as, “in Germany, particularly since the early 1980s…[the] tendency has often been criticized as escapism, as signifying a withdrawl from the political sphere into some kind of dream world, divorced from reality and thus leaving power in the hands of men” (Mies 501).

Zora Neale Hurston not only narrates and critiques the ecological depredations of her time, she also explores and exposes the racial, socioeconomic, and gendered interpenetrations of environmental consciousness and inhabitations. She edges towards all kinds of ecofeminisms (Social/ist, Cultural, Affinity, Materialist, Spiritual, Radical, Liberal, Existential Ecofeminism) in her body of work and life. And it goes without saying that Hurston’s work and ideas are the fountainhead of Black feminist thought but she also encapsulates within the germs of an ecofeminist sensibility.

2.1. An Exploration of the Sensuous of Ecology and Female Sexuality in Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937)

Zora Neale Hurston’s most acclaimed novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937) juxtaposes the sensuous side of ecology with that of female sexuality and sensuousness, through the epiphany of the blossoming pear tree. It helps the writer relate her readers the ideas of environmentalism, feminism (more so womanism), and a pantheistic vision of spirituality. The third person omniscient narrator reveals, “Janie saw her life like a great tree in leaf with the things suffered, things enjoyed, things done and undone. Dawn and doom was in the branches” (Their Eyes8). Janie Crawford, the female protagonist of the novel is therefore the “blossoming pear tree of the backyard” (Their Eyes10), personified. Hurston through her act of personification, then be it the pear tree, the lake or the storm, at once bursts the anthropocentric view, keeping the human and the nature on the same pedestal—which is derivative of the idea that nature has its own individual identity. That it is an entity in itself is an ecocentric understanding.

Though personification is often charged of andropocentricism itself, the text makes evident that men and women, unlike the gender identities attached to them, are equally integral parts of the environment. The “revalation” that Janie is “summoned to behold” on a spring afternoon in West Florida, at the age of sixteen, under a tree, naturalizes the roles of both, men and women. “[T]he dust bearing bee” represents manhood, whereas “the tree” represents womanhood (Their Eyes 11). The narrator reveals, “She saw a dust-bearing bee, sink into the sanctum of a bloom; the thousand sister-aclyxes arch to meet the love embrace and the ecstatic shiver of the tree from root to tiniest branch creaming in every bloom and frothing with delight. So this was a marriage!” (Their Eyes 11). In order to understand the significance of this image, it is pertinent to understand the intricacy of this celebratory image of nature.

On the most basic level, it may be stated that the potential of a woman to bring life, her sensuousness, her beauty, and her femininity has been paralleled to the life creating character of nature in its most fine spectacle. Womanists share a similar sentiment in their celebration of the female body. It must, however, be noted that Hurston’s ecofeminist stance complies with that of Sherry Ortner and Ynestra King, who recognize the middle position of women within the culture/nature dualism. Sherry B. Ortner in the essay, “Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?” (1974) asserts:

Woman is not “in reality” any closer to (or further from) nature than man-both have consciousness, both are mortal. But there are certainly reasons why she appears that way,…: various aspects of woman’s situation (physical, social, psychological) contribute to her being seen as closer to nature, while the view of her as closer to nature is in turn embodied in institutional forms that reproduces her situation. (86)

Hurston’s stance may appear as essentialist on initial acquaintance but in reality it is a method of claiming one’s Otherness. Kathleen Kerr remarks:

For the African-American writer Toni Morrison,…, ‘black matters’ and ‘the people who invented the hierarchy of “race” when it was convenient for them ought not to be the ones to explain it away, now that it does not ‘suit their purposes to exist’ (363).

The racist western society had associated blacks with the “untamed nature” for long. Yet, the black women could not find a smooth entry into the ecofeminist movement. Both ecofeminists and the womanists, even though they reject any outright claim to biological determinism, do accept unanimously the closeness of the female to nature, to the extent of her being an intermediary between nature and culture because of the male’s self-created disconnect with nature. Both celebrate womanhood, but both are aware of the political benefit of the action.

Hurston’s stance (of accepting Otherness for gaining a sense of identity) becomes evident from the love she holds for her “roots.” She was a promoter of her culture and her work permeates with folklore, anthropology, voodoo, and a local dialect and sensibility. She was a source of constant annoyance for her fellow artists from the Harlem Renaissance (such as Langston Hughes), who wished to distance themselves from their cultural roots and embrace the new international forms available. That, she reclaims an ecofeminist space for African-American women, much before the idea became contestable, is evident from her association of the African-American black culture with nature. Scott Hicks confirms this association in “Zora Neale Hurston: Environmentalist in Southern Literature.” Hicks establishes that anthropology for Hurston was like “natural history.”1 This was because folklore and myths arise from man’s understanding of nature and its laws. And that voodoo helps Hurston locate the sacred in the realm of female sexuality and nature.2 Secondly, Hurston through the text does not seem to refute the charge of libidinousness often cast against the African-American women. The eroticized image of the pear tree legitimizes eroticism as a natural extinct within nature and all life. It is quite obvious that the link of eroticism-nature-life qualifies that sexuality is not something to be associated with race. Such an image of eroticism establishes Hurston’s allegiance to the classic blues tradition3 as opposed to that of the club movement.4 But Hurston manages to elude the charge often made against the tradition. The charge that the classic blues tradition certifies, in a way, that the African-American women are over-sexual. This, Hurston does by associating comparatively subtler images of the sexual with Jaine Crawford.

Greta Gaard, in the journal article titled, “Toward a Queer Ecofeminism” contributed for the journal Hypatia, “examine[s] various intersections between ecofeminism and the queer theory, thereby demonstrating that a democratic, ecological society envisioned as the goal of ecofeminism will, of necessity, be a society that values sexual diversity and the erotic” (137). The eroticized image of the pear tree acquaints us as readers to the queer ecofeminist perspective of Hurston that dismantles the discourse associating the erotic with the queer. She instead finds all life to be associated with the instinct.

The overlapping character of culture/nature dualism recognized in ecocriticism is made evident in the text. The wild (wood or animals) and the human (human beings or the man-made environment) enjoy a nourishing coexistence. Her ecofeminist sensibility made her notice the rabbits, snakes, deer, coons, panthers, thousands of buzzards, and other big and small animals joining the humans (be it the Indians, the Seminoles from Oklahoma and Florida, or others) in the exodus just before the hurricane. Nanny’s house is a man-made entity but its backyard has the character of untouched nature and a girl who is untouched, physically and mentally, of any violence because of patriarchy. Here, it would be interesting to enumerate the distinction that Gurleen Grewal points between the blossoming tree of Their Eyes Were Watching God and that of James Wright in the poem, “To a Blossoming Pear Tree.” Grewal points out that while in Jaine’s case the human and the natural are seen as overlapping, in Wright “the two occupied different realms” (Grewal 105). This is evident from the lines, “Perfect, beyond my reach,/How I envy you.” Nature is depicted as something beyond the human reach, yet desirable to man, in its purity and perfection to hear his story of alienation. Hurston in the text, however, naturalizes the human.

The image of the blooming pear tree reminds one of Baruch Spinoza5, who saw God and nature as one. For Spinoza body and mind were not separate entities. Western patriarchal society has often located the two in separate realms but a resolution of the two is characteristic of eco-spiritualism, as in the image of the pear tree. Hurston herself found the divinity in everything and anything, and the consciousness to her was indestructible. Her idea of a pantheistic spirituality coincides with that of the eco-spirituality or the alternative spirituality that the cultural ecofeminists endorse. G.F. Orenstein remarks, “…ecofeminism calls for endarkment-a bonding with the Earth and the invisible that will re-establish our sense of interconnectedness with all things, phenomenal and spiritual, that make up cosmos” (280). Jaine is brought face to face with the eternal truth or the Universal Truth, per se. The tree does not just enmesh in itself the understanding of self alone “in the branches,” rather the ultimate mystery of life (Their Eyes 8). The idea of the pantheistic spirituality has been familiar to the Womanists as well. Gurleen Grewal, speaking of Jaine’s journey towards self states, “More than an adolescent awakening of sexuality or the representation off organic love as many critics including Robert Hemenway and Carla Kaplan suggest, the tree is a vision of Life that becomes a blue print for the soul’s quest’” (104).

Yet, her quest is also towards selfhood and her transformation through this bildungsroman journey shares a deep nourishing relationship with the nature. Each individual character of Hurston’s concocted world within the text alongside nature initiates Jaine Crawford, in a direct or indirect way, a step forward towards this goal. The geographical dimension of her journey corresponds these steps, making clear the two strategic motives of Hurston. Firstly, the journey establishes the connect between the exploitation of women and nature within the patriarchal ideological discourse (the chief tenet of ecofeminism). Secondly, it is incorporated to make the womankind aware as to how travel can help them explore themselves in a society that associates women essentially with domesticity. Gordon E. Thompson affirms, “She uses travel to contrast the negatives of domesticity with the benefits of exploration and its self-affirming powers, be such psychological or literary and geographical” (738).

Ecofeminism is closely associated with the Deep Ecology. As a contemporary ecological philosophy, deep ecology claims that all beings share the same rights to live and to prosper, and are endowed with worth, apart from utility. It emphasizes the interdependence of nature and non-human life, taking a holistic view of the world, recognizing that separate parts of the ecosystem (humans included) function as a whole. Such a claim is based on the understanding that the right to live is a universal fight and no single species is entitled to more or less of it. Warwick Fox in the book, Towards a Transpersonal Ecology (1990) states this metaphysical idea stating that all beings are aspects of a single unfolding reality. Spinoza and Hurston seem to agree through their works. The philosophies of Spinoza and deep ecology connect on the idea of self-realization. Both ecofeminism and deep ecology put forward this intricate image of the self-which is a sort of a dynamic identity constructed as a result of its relationship with other forms of life.

Keeping such a view of self we shall further analyze Jaine’s coming to terms with self through her odyssey from the backyard of the Washburns, to the house that Nanny arranges when Jaine is old enough to understand the biases against her color, to the Logan Killicks’ house, to Eatonville as Joe Starks wife, to the “muck” at the Everglades, and back to Eatonville. The pear tree at Nanny’s house is a celebratory image of nature untouched by man. It serves as a blue print of an ideal woman-man relationship in the eye of Jaine. She assimilates that the “bee” (manhood) and the “tree” (womanhood) are equally integral parts of the environment (equally close) and that the balance of nature can be restored only when the two aspects are at par with each other. Such a view reminds one of the concept of androgyny even though it has been criticized6 by feminists for its priority of andros (male) over gyne (female). Hurston in the image also seems to suggest a balance of male and female that Virginia Woolf suggests in A Room of One’s Own, a work that contributed immensely in understanding gender as a cultural construct. Once seeing the sight of a girl and a man get into a taxi from her window, she claimed:

…sight of the two people getting into the taxi and the satisfaction it gave me made me ask whether there are two sexes in the mind corresponding to the two sexes in the body, and whether they also require to be united in order to get complete satisfaction and happiness?...The normal and comfortable state of being is that when the two live in harmony together, spiritually co-operating. If one is a man, still the woman part of the brain must have effect; and a woman also must have intercourse with the man in her. Coleridge perhaps meant this when he said that a great mind is androgynous. (147-48)

Seeing man and woman as equally integral, Jaine sets to find a true “marriage” (Their Eyes11). However, she has many hurdles to overcome and Nanny, for instance, proves one.

Nanny, Jaine’s grandmother was the only family she had. On our first encounter of her Nanny “looked like the standing roots of some old tree that had been torn away by storm” (Their Eyes 12) because Johnny Taylor had appeared through “pollinated air” (Their Eyes 11), “bathed in the golden dust of pollen” (Their Eyes 12) and Jaine in the flow of the moment had kissed him. Nanny wanted to see Jaine “married right away” (Their Eyes 12), a decision she had come to owing to her experiences as a woman born into slavery. She had gone through much in life-having been impregnated by her master, being subjected to much physical and mental abuse from his wife, and her daughter (and Jaine’s mother), Leafy having had to face constant threat of being sold as a one month old. Because of this Nanny even had to escape “to de swamp by de river” (Their Eyes 18). Leafy’s abduction and rape by her school master, in spite of Nanny’s will and effort to give Leafy what she herself could not get as an African-American slave woman, she “took to drinking’ likker and stayin’ out nights” (Their Eyes 19). She single handedly had to take care of Janie, in spite of her old age.

Nanny did not wish to see Jaine turn to a “spit cup” for men. Through Jaine’s marriage to Logan Killicks, she wanted to ensure protection and respect for her granddaughter. She was well aware of the “nigger woman” being “de mule of de world” (Their Eyes 14). Slave narratives often recognize blacks being negatively identified with animals but here this colonized image (degrading any association with second rate life) created by Nanny in Jaine’s eye has been subverted through Jaine’s association with nature and her sympathetic feeling for Matt Bonner’s yellow mule that eventually dies. A similar point is made by Christine Gerhardt in the article, “The Greening of African-American Landscapes: Where Ecocriticism Meets Post-Colonial Theory” for the journal The Mississippi Quarterly, wherein she undertakes an ecocritical/postcolonial reading of Alice Walker’s autographical essay “Am I Blue?” (1986). Walker, Gerhardt explains, understood, “white people’s treatment of animals as displaced repetition of slavery” but “[a]part from Walker’s concern for racial and environmental domination” she also believed in identification with nature as a “possible subversive strategy’ towards decolonization (515+). “Walker’s vision that identification with the Other can serve as a way out of perpetual subjugation,” Gerhardt asserts, “is based in the idea that direct communication between humans and non-human beings is possible” (515+). Hurston makes clear that Jaine, “often spoke to falling seeds and said, ‘Ah hope you fall on soft ground,’ because she had heard seeds saying that to each other as they passed” (Their Eyes25).

However, Nanny did not just prove a hurdle. She aided Jaine in her journey to self by passing off as an example of a woman who, “…saw the constraints on her own life but managed to keep the will to resist alive. Moreover, she tried to pass on that vision of freedom from controlling images [of oppressive patriarchy] to her granddaughter” (Collins 101). But Nanny’s perception of respectability that a black woman could achieve marrying a much older man, settled and with property like Logan Killicks, to sit on high porch like the white women folk, could not bring happiness to a woman like Jaine, for whom his “sixty acres uh land right on de big road” could not be taken “tuh heart” (Their Eyes 23). Logan’s house when Jaine first saw it looked like “a lonesome place like a stump in the middle of the woods,” devoid any favour (Their Eyes 21). Nature in this part of the text is depicted as barren as Logan himself. While Jaine is a tree-in-spring Logan is as insensate as the tree stump. He is sexually repulsive to Jaine who associates him with images like “skull head” (Their Eyes13) and “mule feet” (Their Eyes 24). He is unclean and inarticulate. He sees Jaine as some kind of a capital investment who wishes to see Jaine work herself like a mule, just in the manner his first wife did.

Logan Killicks’ image as a farmer; chopping wood, plowing the land with the mule, and threatening Jaine of death with the same “ax” he uses to chop wood presents a picture of a phallogocentric-andropocentric male who commits violence against women and nature in a like manner (Their Eyes 31). He tends the land only to get a profit out of it. All dualisms see “the Other” as an entity having no end of its own and to be existent only to serve as a resource for the master. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick in the work, Epistemology of the Closet (1990) called this approach towards the Other as “Instrumentalism.” Killicks remarks, “You ain’t got no particular place. It’s wherever Ah need yuh” (Their Eyes 31). In a way such an anthropocentric view of the barn and women that Logan Killicks holds also reiterates the idea of the “light Greens” as Jonathan Bate defines in his The Song of the Earth (2000) as an attitude that makes humans value nature because it environs humanity and contributes to our well-being. Ironically, Killicks (a name that anticipates his violence) subjugates Jaine to the same position of a “mule” that Nanny wanted her to evade, forcibly marrying her to him.

Jaine soon realizes “that marriage did not make love” (Their Eyes 25). So she decides to elope with Joe Starks, a charming young man, who Jaine sees as a “bee for her bloom” with the promise of “flower dust and springtime sprinkled over everything” (Their Eyes 32). Starks offered Jaine, an escape from the drudgery of his life at the barn, and the dreams of a happily ever after, as they drive towards the “Green Cove Springs.” A place that by its name anticipates the green, the spring, and love; an atmosphere congenial for a true marriage according to Jaine. Like a womanist she followed her heart as she “walked on, picking flowers and making a bouquet” (Their Eyes 32), towards herself. Her elopement was a decision guided by a sudden feeling of newness and change “[e]ven if Joe was not there waiting for her, the change was bound to do her good” (Their Eyes 32). While defining the term womanist, Alice Walker in her work In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens (1983) associated traits like outrageousness, audaciousness, and wilful behaviour with a womanist. Such traits are visible in Jaine at this point of time in life (her arguments and elopement). She is a slightly more powerful image of an African-American woman than Nanny or Leafy, who serve as examples of objectification of women, even though she herself is an object for Killicks, her act is apparently self-definatory in the manner of women in the blues tradition.

Joe Starks, however, also treats Jaine as property. Tony Taylor’s remarks bear as witness, “Brother Starks, we welcomes…yo’ belov-ed wife, yo’ store, yo’ land-‘” (Their Eyes 42). He is a kind of a “mimic man” who thinks of himself as God and dreams of being a “big” man of Eatonville. His mimicry and his money however does establish him as the mayor (alongside his work as a postmaster, as a storekeeper, a landlord, and as the voice of the town) but he fails to satisfy Jaine’s vision of “he bee.” He too, much like Killicks thought of women and nature as means of making profit. Hurston created his image in the light of the Christian God giving him the tag line, “I God.” Richard Kerridge in the essay, “Environmentalism and Ecocriticism” enumerates how the “environmentalist historian Lynn White Jr. has described Christianity as the most anthropocentric of religions, because of God’s command, in Genesis 1:26, that man should have dominion over the other creations of the earth” (Kerridge 537). The Bible states that God punished man and woman after they tasted the forbidden fruit from the tree of knowledge. He punished man commanding of him his services forever, while He punished the woman doubly commanding her to serve Him by serving man and bearing the pain of childbirth. In the light of such an image of God, Starks appears deeply androcentric and Jaine’s retort to his beratement (he calls her old and ugly) is symbolic of a retort to a deeply biased ideology, with which she treads a step further in her journey.

Starks’ image is that of a man who ravages the will of a woman and who constantly ravages the environ he is in. Noticing the scent houses, the sand, and palmetto roots at Eatonville he remarks, “Why, ‘taint nothing but raw place in de woods’…De place needs buildin’ up” (Their Eyes 34-43). So he constantly engages in violence against nature in order to build it up. He engages Tony and Coker to carpenter for the store. He sends men to the swamp to cut the “finest and the straightest cypress post” (Their Eyes44). He tries to take the place of God, creating lamp posts for the “Sun-maker sends it tuh bed at night” (Their Eyes 45). Prayers offered by Davis and Mrs Bogles further confirm the analogy. The emotional incompatibility between Jaine and Starks keeps growing wider owing to the increased restrictions imposed on her. She is not allowed to sit with her fellow people, she is to keep her hair in a head-rag while in store, so on and so forth. It must be noted that hair is a symbol of sexuality and Joe Starks had denied her, though metaphorically, the sexuality she associated herself with in her vision of her paer tree. When Starks slaps Jaine for not being able to fix a meal she could no longer see “blossoming openings dusting pollen over her man” (Their Eyes 46). Just as Jaine’s marriage with Killicks sealed with a slap from Nanny was doomed, Sarks; slapping Jaine withers this relationship as well. In the scene where she retorts his beratement attacking his countenance saying he himself looked like “de change uh life” (Their Eyes 79) she gains herself to a certain extent, through self-expression, but the lost domination leaves Starks deeply upset and slowly leads to his death.

Amidst all this action a surrealistic episode has been incorporated within the narrative, that of the buzzards conversation after the Eatonville citizens’ burial of a local mule, an episode borrowed from the “Mule Bone.” Hurston through the episode depicts the sense of selfhood amongst these creatures. Just as man is close to nature (Jaine’s connect with the pear tree) it also shares humanly traits (the buzzards speak). All life is connected in their association with the truth of birth, growth, and death. Robert E. Hemenway, Zora’s official biographer, offers enlightening comments for the scene, that one can only conform with, he asserts, “…it is as natural for buzzards to speak as for bees to pollinate flowers, as for a human being to be a “natural man.” When not a part of the organic process of birth, growth, and death, one is out of rhythm with the universe” (234). That Jaine herself requires to reach a state of this kind of selfhood-where all life is in harmony and all life has equal worth, ignoring all biases that corrupt society, is hinted at. Jaine’s being denied attendance to the ceremony by Jody Starks is not only a sign of exclusion but also an attempt at the part of male to claim transcence over immanence, dissociating himself from the natural (as all androcentrics) that works on the principle of organic unity that combines all life and grieving death, which is seen as nothing but a transitory phase in the cycle of life by those believers of immanence.

In the mule burial scene where men make speeches only to derive pleasure (as in case of Joe to boost his “I God” ego) Hurston offers an ecofeminist perspective for the reader. Irrelative of the non-seriousness and hypocrisy of the crowd in addressing the mule as “a citizen” (Their Eyes 60) like themselves and standing on its corpse as if it were a pulpit, Hurston thrusts forward the idea that all humans must restore the right relationship with the environment giving away all thoughts of speciesism, understanding ourselves as animals as well. She as if makes outright mockery of the second theory of the Ethical Philosophy that man has the sole responsibility to treat right and take care of the environment and the animal because of “his” superiority of reason. That a pet-owner relationship is always marked with oppression is also hinted at through Matt’s relationship with his mule. An oppression that is identical with the oppression Nanny recognizes in the lives of African-American women that subjugates them as “mules.” And even the oppressive concept of the White man’s “pet negro” per se, for that matter. Greta Gaard in a magazine article, “Ecofeminism on the Wing: Perspectives on Human-animal Relations” (2001) states:

…feminists who politicize their care for animals see a specific linkage between sexism and speciesism, between the oppression of women and the oppression of animals….Feminists and ecofeminists alike have noted the ways that animal pejoratives are used to dehumanize women,…. (19+)

Jaine, the representative of all oppressed colored women and the mule that represents all non-human life, are the sights of speciesism. The five conditions that Iris Marion Young listed in the work Justice and the Politics of Difference categorizing the oppressed as revisited by Gaard in the said article are—exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural imperialism, and violence. All these are evident in the depiction of nature and women in the text.

Starks leaves Jaine with property and money. Soon after his bereavement, a much younger man, a labourer, and a guitar-player by the name of Vergible “Tea Cake” Woods wins Jaine’s heart. Tea Cake loves her for the person she is. He treats her like an equal exposing her to a whole new things, unlike her previous restrictive relationships, like fishing, shooting, playing games like checkers, so and so forth. The house that had previously sounded of “loneliness” on his arrival gains flavour. But they move to “the muck” in the Everglades. Unlike the barren suburbs at Eatonville, Everglades has a soil that is rich, black, and fertile. People there work hard together and party together, and are in complete harmony with nature. They are as alive as the fertile lands or its wild fruits. Everything seems big and overwhelming to Jaine-big lake Okechobee, big beams, big cane, and big weeds.

Amidst all this Hurston also anticipates (a need for) the Environmental Justice, a concept that emerged in the US in the early 1980s. In spite of the richness of nature in the Everglades there is a line that segregates the plantation owners (the boss men) from the plantation workers. Tea Cake explains Jaine, “…we had tuh git us uh room,” because he says, ‘[t]two weeks from now, it’ll, be so many folks heh day won’t be lookin’ fuh rooms, dey’ll be jus’ looking fuh somewhere tuh sleep” (Their Eyes 129). The South African Environmental Justice Newteorking Forum defined environmental justice as social transformation directed towards meeting basic human needs and enhancing our quality of life-economic quality, health care, housing, human rights, environmental protection, and democracy. In linking environmental and social justice issues the environmental justice approach seeks to challenge the abuse of power which results in poor people having to suffer the effects of environmental damage caused by the greed of others.

Hurston had an eye which could understand the susceptibility of the black people in Florida to tropical hurricanes because of poverty, Jim Crow laws, landscape and the inability of the communities to move to safer grounds. Dawood H. Sultan and Deanna J. Wathington in their essay, “Premonition: Peering through Time and into Hurricane Katrina,” comment:

The same socioeconomic, political, and historical factors which determined individual and collective health status, safety, and general well-being of New Orleans’ poor blacks before the arrival of hurricane Katrina [2005] in the city were the ones which afflicted the black folks in Hurston’s muck. (159)

Josie P. Campbell gives an interesting insight on Tea Cake’s character, Campbell asserts:

Tea Cake is associated with the god Orpheus, the maker of music, and with the world of nature itself; Vergible seems to be the veritable god of living things; of the woods, of the earth-the fertile muck-of the sun. He arrives with the air into Jaine’s life. He literally and metaphorically carries with him the seeds of life itself in his serious game of love. (68).

Unlike Starks who wanted to sit on a high position aping the whites while helping his folks, Tea Cake’s approach to life is that of hospitality. Tea Cake represented the real ‘bee’ that Jaine was looking for all her life.

Jaine had always wished to find the ‘bee’ but surely as Robert E. Hemenway suggests, “Jaine finding the one true bee for her blossom is hardly a satisfactory response from a liberated woman” (235). As Hemenway suggests, Jaine at this point of time in life is a woman who gained a sense of self, her childhood dream of a “bee” stands “tempered by growth and time” (235). It is now incorporated with the metaphor of the horizon. Tea Cake is also associated with the horizon, he is the “son of Evening sun.” Hemenway asserts that, “…the horizon motif illustrates the distance one must travel in order to distinguish between illusion and reality, dream and truth, role and self (235). The point becomes clear when Jaine shoots Tea Cake in his madness out of a will to survive. She has now gained a sense of selfhood. Even though she loves him dearly she acts as the agent of his death. She defies the traditional notion of love which encourages female masochism. Her understanding of the pear tree and the bee had given her a sense of her own sensuality and equality of man and woman in nature, but her vision of the horizon had added to this understanding a sense of self-worth. She tends Tea Cake in his last days in spite of the danger but does not sacrifice herself in death at his hands. She lives up to the womanist stance, as well as the ecofeminist notion, hence. She cares for all life—including women but she shuns conventional essentialism attached with women almost simultaneously. But as critics point out, men who commit wrong against woman in Hurston’s texts are doomed to death. Tea Cake too is doomed after his succumbing to jealousy because of Mrs. Turner’s malice.

The hurricane at Everglades too is a significant symbol after Tea Cake had “whipped Jaine” (Their Eyes 147) the storm hits the lake. As if the balance of nature, symbolized in the image of the tree and the bee had been disturbed and the pantheistic god was upset. As Karla Holloway suggests, that the fury of nature, “…is a lesson for Jaine, who has been linked with natural imagery throughout the story and who needs to learn the potential strength of her own independence” (65). The love story ends with Jaine returning to Eatonville. She tells Phoeby, “Ah done been tuh de horizon and back and now ah kin set heah in mah house and live by comparisons” (Their Eyes 191). Hurston’s depiction of the relationship between Tea Cake and Jaine at Everglades is an ideal situation, that she constructs as an ecofeminist, per se, for her readers to witness. Jaine’s return to Eatonville symbolizes her return to “the real” from “the ideal—ecofeminist utopia.”

Jaine is projected throughout as closely connected to nature. In Jaine’s character Hurston combines an element of voodoo to enhance the effect. Critics, like Daphhne Lamothe in the journal article, “Vodoo Imagery, African-American Tradition, and Cultural Transformation in Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Watching God,” have recognized the implicit presence of the goddess, Ezili in her. Both the two aspects of the spirit of Ezili are incorporated, namely, Ezili Freda, the goddess of love and Ezili Danto, the black goddess associated with rage against authority especially to Christianity’s call for submissiveness. Ecofeminism too, it must be noted, calls for, a “spiritual vision that constructs the earth as a sacred being…the Goddess or Gaia” (Brammer), and a feminist (in this case womanist) sensibility alongside an environmentalist vision.

Epistemology

Interestingly, Jaine’s association with nature also depicts ecosexuality. In 2011, Annie Sprinkle and Beth Stephens published the Ecosex Manifesto, that declared all as part of and not separate from nature, and therefore qualified all the sexes as ecosexual. By this they implied that sexuality is ecological, and that there exist interconnections or alternate relationalities, between the human and the more-than-human world. Such an understanding is an advocating of inter-species politics that thwarts anthropocentricism, and establishes that nature too has agency, and opens a new dimension for future research. It may be stated that, their (all victims of oppression) eyes were watching “God,” the “God” that manifest itself in nature—in all life that it views as equivocal. A “God” that marks fertility, love, and benevolence represented in the images of nature and, a “God” who has a wrathful aspect as well clearly depicted in the images of the hurricane.

References

Allan, Tuzyline Jita. “The Color Purple’: A Study of Walker’s Womanist Gospel.” Alice Walker’s ‘The Color Purple.’ Ed. Harold Bloom. Chelsea House, 2000.

Bate, Jonathan. The Song of the Earth. Picador, 2000.

Brammer, Leila R. “Ecofeminism, Environment, and Social Movements.” National Communication Association Convention. Gustavus Adolphus College, New York, 1998. Reading. Homepages.gac.edu./~Ibrammer/Ecofeminism. 20 Sept. 2010.

Campbell, Josie P. Students Companion to Zora Neale Hurston. Greenwood Press, 2001.

Cheng-Levine, Jia-Yi. “Teaching Literature of Environmental Justice in an Advanced Gender Studies Course.” The Environmental Justice Reader: Politics, Poetics, and Pedagogy. Edited by Join Adamson, Mei Mei Evans and Rachel Stein, University of Arizona Press, 2002.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge, 2009.

Davis, Angela Y. Women, Race, and Class. Vintage, 1983.

Ferguson, Kathy E. The Man Question: Visions of Subjectivity in Feminist Theory. University of California Press, 1993.

Fox, Warwick. Toward a Transpersonal Ecology. Suny Press, 1995.

Gaard, Greta. “Ecofeminism on the Wing: Perspectives on Human-animal Relations.” Women and Environments International Magazine. Fall 2001, pp. 19+. http://www.questia.com/PM/qst?a=o&d=5036767492. Accessed 12 Jan. 2011.

Gaard, Greta. “Toward a Queer Ecofeminism.” Hypatia, vol. 12, no.1, 1997.

Gerhardt, Christine. “The Greening of African-American Landscapes: Where Ecocriticism Meets Post-Colonial Theory.” The Mississippi Quaterly, vol. 55, no. 4, 2002, pp. 515+. http://www.questia.com/PM/qst?a=o&d=5001999484. Accessed 7 Feb. 2011.

Grewal, Gurleen. “’Beholding ‘A Great Tree in Leaf’”: Eros, Nature, and the Visionary in Their Eyes Were Watching God.” “The Inside Light”: New Critical Essays on Zora Neale Hurston. Edited by Deborah G. Plant, Praeger, 2010, pp. 103-12.

Helbling, Mark. “’My Soul was with the Gods and My Body in the Village’: Zora Neale Hurston, Franz Boas, Melville Herskovits, and Ruth Benedict.” The Harlem Renaissance: The One and the Many. Greenwood Press, 1999.

Hemenway, Robert E. “Crayon Enlargements of Life.” Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography. University of Illinois Press, 1977, pp. 234-35.

Hicks, Scott. “Zora Neale Hurston: Environmentalist in Southern Literature.” “The Inside Light”: New Critical Essays on Zora Neale Hurston. Edited by Deborah G. Plant, Praeger, 2010, pp. 113-25.

Hurston, Zora Neale. Dust Tracks on the Road: A Restored Text by the Library of America. Edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., 1942, Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006.

Hurston, Zora Neale. Their Eyes Were Watching God. 1937. Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2006.

Hurston, Zora Neale. “What White Publishers Won’t Print.” I Love Myself When I Am Laughing…& Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive: A Zora Neale Hurston Reader. The Feminist Press, 1979, pp. 169-73.

Kerridge, Richard. “Environmentalism and Ecocriticism.” Literary Theory and Criticism. Edited by Patricia Waugh, OUP, 2006, pp. 530-43.

Kerr, Kathleen. “Race, Nation, and Ethnicity.” Literary Theory and Criticism. Edited by Patricia Waugh, OUP, 2006, pp. 362-85.

Lamothe, Daphne. “Vodou Imagery, African-American Tradition and Cultural Transformation in Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God.” Callaloo: A Journal of African-American Arts and Letters, vol. 22, no. 1, Winter 1999, pp. 157-75.

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider. Crossing Press, 2007.

Mies, Maria, and Vandana Shiva. “Ecofeminism.” Feminisms. Edited by Sandra Kemp and Judith Squires, OUP, 1997, pp. 497-503.

Orenstein, G.F. “Artists as Healers: Envisioning Life-Giving Culture.” Reweaving the World: The Emergence of Ecocriticism. Edited by I Diamond and G.F. Orenstein, Sierra, 1990, pp. 279-86.

Ortner, Sherry B. “Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?” Woman, Culture, and Society. Edited by M. Z. Rosaldo and L. Lampshere, Stanford UP, 1974, pp. 68-87.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Epistemology of the Closet. University of California Press, 1990, pp. 42-56.

Starkey, Michael. Wilderness, Race, and African Americans: An Environmental History from Slavery to Jim Crow. Diss. University of California, 2005. n.p., n.d. N. pag. http://erg.berkely.edu/people/starkey%20paper%20FO5.pdf. Accessed 14 Aug. 2010.

Stephens, Beth, and Annie Sprinkle. The Ecosex Manifesto. https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.ucsc.edu/dist/8/1076/files/2021/04/manifesto-1point0.pdf. Accessed 23 Dec., 2022.

Sturgeon, Noel. Ecofeminist Natures: Race, Gender, Feminist Theory, and Political Action. Routledge, 1997.

Sultan, Dawood H., and Deanna J. Wathingron. “Premonition: Peering through Time and into Hurricane Katrina.” “The Inside Light”: New Critical Essays on Zora Neale Hurston. Edited by Deborah G. Plant, Praeger, 2010.

Thompson, Gordon E. “Projecting Gender: Personification in the Works of Zora Neale Hurston.” American Literature, vol. 66, no. 4, Dec. 1994, pp. 737-63.

Walker, Alice. “Am I Blue?” Selected Writings 1973-1987. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989.

Walker, Alice. The Color Purple. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982.

Walker, Alice. In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One’s Own. Hogarth P, 1929, pp. 147-48.

Wright, Richard. 12 Million Black Voices. 1941. Echo Point Books & Media, 2019.

Young, Iris Marion. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton University Press, 1990.

Notes

1

A term by Suzanne Clark used in the paper compiled by Scott Hicks. Clark had asserted, “Anthropology as Hurston studied it with Franz Boas was a close kin to natural history, with a discursive status similar to the natural history descriptions of the Grand Canyon (for geologist/anthropologists like John Wesley Powell) or the fish of the Amazon River (for biologists like Louis Agassiz)” (87-94), in “The Florida Flavor.”

2

An argument that Hicks makes on the basis of Rachel Stein’s assertions in Shifting the Ground: American Women Writer’s Revisions of Nature, Gender, and Race (1997).

3

The classic blues tradition of women, historians claim, is opposed to the club women tradition. It is often read as centrally concerned with expressing desire. In this tradition classic blues singers and narrators are represented as independent and as sexual objects for political reasons-to counteract racist sexual stereotypes. It establishes African-American women as sexually independent, self-sufficient, creative, assertive, and trend setting. (Source of information: Batker, Carol. “Love Me Like I Like to Be’: The Sexual Politics of Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God the Classic Blues and the Black Women’s Club Movement.” African American Review 32.2 1998): N. pag. Web. 9 Feb. 2011.)

4

The club movement women associated with the regulation of desire and an outright denial of racist ideologies that represent African-American women as libidinous.

5

Spinoza believed God exists philosophically, and is abstract and impersonal. Spinoza’s system imparted order and unity to the tradition of radical thought, offering powerful weapons for prevailing against authority. As a youth he subscribed to Descarte’s dualistic belief that body and mind are two separate substances, but later changed his view and asserted that they were not separate, being a single entity. He contended that everything that exists in Nature (i.e. everything in the universe) is one reality (substance) and there is only one set of rules governing the whole of the reality. He, therefore, viewed God and Nature as two names for the same reality. His identification of God and nature was explained in his posthumously published Ethics.

6

Critics like Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar have even suggested the alternative term gyandry, though it has not gained much acceptance. It has been realized that assigning just two sexes to all life is a limiting thought.

ISSN: 1137-005X

30

Num.

Año. 2023

RE-ARTICULATION IN ZORA NEALE HURSTON’S THEIR EYES WERE WATCHING GOD

Divya Sharma

Department of English, University of Jammu,India